On the morning of May 9, 1972, the USS Coral Sea catapulted a strike package of three A-6 Intruders and six A-7 Corsairs into the morning sky. The aerial campaign against North Vietnam, paused in 1968, had resumed five weeks before in response to the Easter Offensive. Task Force 77, then consisting of six carriers, had been flying combat missions against the North for more than a month, but this mission was different. Slung underneath the wings of the Intruders were 1,000-pound Mk-52 antiship mines. The Corsairs carried the smaller, 500-lb Mk-36. The large mines were destined for the inner channel of Haiphong’s busy harbor, with the smaller ones destined for the outer channel. Operation Pocket Money, the devastatingly effective naval blockade of North Vietnam was on.

When the U.S. Navy finally cleared the mines after the Paris Accords that ended the war, the sun set on the air delivered mine. The risk to the minelaying aircraft was too great, a point driven home by the Navy’s last aerial mining mission in 1991, which resulted in the loss of an A-6 and its crew.

That all changed in September 2016. During the biannual Valiant Shield exercise, the United States demonstrated a potentially devastating new mine capability – one that takes advantage of off-the-shelf precision capabilities added to antiship mines. For the first time, the Joint Force can lay a precision minefield in a single pass from any altitude – and can even do it from a distance. The Skipjack JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition) variant and the smaller winged extended range Flounders have revolutionized American naval mining capabilities without an extensive and costly development program.

In an increasingly globalized world where the lifeblood of many nations flows via global shipping lanes, the potential for these weapons to cripple an adversary’s maritime transport capability offers an asymmetric advantage for U.S. Forces.

History

Sea mines are obviously an antiship weapon, but not necessarily an anti-warship weapon. In World War II, both the British and the United States had emplaced mines defensively, in order to inhibit U-Boat operations in Atlantic waters. The primary use of mine warfare in the Pacific War was offensive, placed to interdict harbors and chokepoints. The vast majority of mines were laid by land-based airpower, interdicting Japanese transport from Rangoon to Japanese home waters. Mines were even hauled over the Himalayas to be laid in the Yangtze River. They were a key part of a maritime interdiction effort that devastated the Japanese merchant marine and dismantled the seaborne flow of resources, starting years before the first B-29 reached the Japanese islands. In the closing months of the war, mines laid by aircraft accounted for more Japanese ships sunk or damaged than all other sources combined.

In Vietnam, mining was under consideration from 1964, but was regarded as too escalatory by policymakers in Washington. Admiral Thomas Moorer, as the chief of Naval Operations from 1967 to 1970 and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1970-1974, had been among the officers advocating for mining to cut off military supplies in bulk where they entered Vietnam, rather than trying to interdict individual trucks and sampans downstream from their supply points. Indeed, Haiphong had been mined before – starting in November of 1942. Thirty years later, the Easter Offensive provided the impetus and President Richard Nixon authorized the operation.

An A-7 Corsair of VA-22 loaded with Mk-52 mines on USS Coral Sea, 1972 (photo by Fotis Dee, US Navy)

The effect of Operation Pocket Money was substantial. At the time, 85 percent of all imports (including war materiel) and 100 percent of the oil needed by North Vietnam came through Haiphong harbor. After the mining effort started, the port was shut down to maritime traffic. Nothing larger than a fishing vessel left or entered the port until the United States swept the harbor after the Paris Accords. Air-delivered mines had shattered the sea-dependent supply line that North Vietnam relied on. Combined with the air interdiction efforts against Vietnamese rail transport in Linebacker I, Pocket Money arguably brought about the termination of U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

The key to Pocket Money’s success, like earlier mining efforts, was that antiship mining is effectively an anti-commerce operation. Contemplating offensive mine warfare as a method of sinking naval vessels is missing the boat – mistaking the tactical effects from the strategic implications. The object of aerial mining is to strangle an opponent’s economy, disrupt seaborne logistics, and constrain power projection. In an increasingly globalized world, the implications of this kind of denial strategy are monumental.

Enter the JDAM

Pocket Money was the last hurrah of the air-delivered antiship mine. While the United States maintained them in the inventory, their utility lapsed as the danger of flying predictable, low-level mining patterns increased. In World War II, B-29s laid bombs from as high as 30,000 feet, but their accuracy was poor and large numbers didn’t even land in the water. Without the mass of entire bomb groups dedicated to aerial mining, release altitudes shifted down to improve accuracy with a much more limited number of mines.

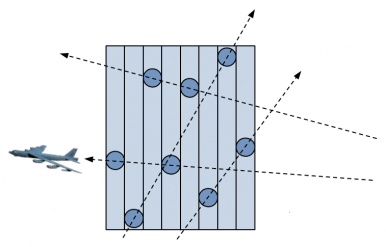

Traditional mining – to get one mine in each “lane”,

the minelayer must make three low, slow passes. (US Navy)

The last attempt to mine a seaway came during Desert Storm, when Jackal 404 (an A-6 Intruder) was lost attempting to mine the Um Qasr waterway on the third night of the war. The reason for this was the nature of mining deliveries. Aircraft have to slow down and go low to deliver mines – the first cluster of mines laid in Haiphong were dropped at 300 feet and 360 knots. Even then, the accuracy is low – placing a mine within hundreds of yards is accepted. To get a credible minefield, aircraft have to make multiple drops; timing and navigation are critical. Against an alerted adversary with the wherewithal to defend its own port facilities, minelaying is a suicide mission.

Enter the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM). In Vietnam the U.S. mine inventory gravitated away from purpose-built mines to conversions of general-purpose bombs, called Quickstrike mines. Fuse a bomb body to detonate on impact, and it’s a bomb. Add a guidance kit and it’s a precision weapon. Equip that same bomb body with magnetic/seismic sensors where the fuse would go, and it’s a mine. If the Pentagon could equip a bomb with a precision kit, then it could do the same with a Quickstrike mine. So it did – Enhanced Quickstrike mines were brand new weapons assembled entirely from components already in the inventory.

The first Flounders — Mk-82 bomb bodies before weapon assembly (Image by Col. Mike Pietrucha, U.S. Air Force)

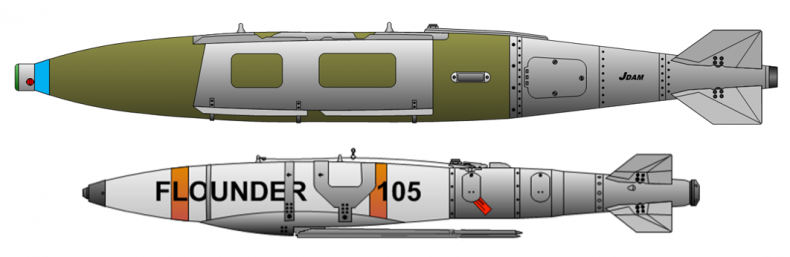

The new Enhanced Quickstrike mines come in two flavors. The 2,000-lb version is the Quickstrike-J, which has the JDAM guidance kit attached and is commonly called the Skipjack. The 500-lb Quickstrike-ER version, called the Flounder, has both a JDAM-ER guidance kit and a pair of folding wings. They mirror the dimensions and weight of their JDAM siblings and have been dropped from the B-52, the B-1, and the F-18.

Using the JDAM kits completely changed the employment concept as well. Now rather than making multiple passes at low altitudes and slow airspeeds, the minelayer can employ weapons at the same tactical airspeeds and altitudes as the JDAM. To make the conversion even more attractive, all of the mines can be released in one go, and the minelaying aircraft does not even need to overfly the minefield. The Flounders, with their extended range wing kit, can be released from distances exceeding 40 miles away. In 1972, the initial minefield in Haiphong’s inner channel consisted of 12 mines delivered by three A-6As using visual navigation and stopwatches. An Air Force bomber aircraft can now potentially lay several similar minefields in a single pass, and do it from standoff distances.

Quickstrike-J (top) and Quickstrike-ER (Image by U.S. Navy)

Strategic Implications

With standoff weapons, stealth aircraft, or both, harbor mining is feasible again. With precision mining, the United States can place the weapons exactly where it wants them. While much attention is given to chokepoints like the Straits of Hormuz or the Straits of Malacca, mining efforts in those waterways would be a blunt instrument, wielded against belligerents and neutrals alike. Precision minelaying can now be tailored to a specific waterway in question, and it need not be in international waters. It is even possible to design a minefield that is a greater threat to vessels traveling in a specific direction (or its reciprocal).

Harbor mining, no longer out of reach, might not only be specific to a country but specific to a cargo, allowing a great deal of selectivity that was previously unavailable. Should we want to prevent oil from entering or leaving a country, we need only mine the oil terminals or their approaches. Liquid petroleum is your target? Those facilities are few and far between and easily located. It is even possible to target certain coastal refineries, preventing specific products from being produced at refineries that have their own oil terminals.

Precision emplacement: these weapons were launched against the same aimpoint. It’s the second time in two tests that weapons have been touching on the seafloor. (Image by U.S. Navy)

For potential adversaries like China or Iran, aerial mining is back on the table. China is almost completely dependent on maritime trade, relying on water transport for 98 percent of its international cargo movement (by tonnage) and half of its domestic movement (by tonne-kilometer). China’s land borders move a large amount of cargo that is nevertheless insignificant in terms of the larger whole. Iran, emerging from sanctions, is itself heavily reliant on seaborne trade. The National Iranian Tanker Company is the world’s fourth largest tanker fleet; six percent of all global seaborne exports come from Iran, including 2.3 million barrels of oil per day. Limiting Iran’s access to seaborne trade is a powerful strategic tool. Even the Russians are vulnerable, because they have so few ports. St. Petersburg alone handles more container traffic than the Russian Far East and Black Sea ports combined — a sixfold increase since 2000, all run through a single port complex at the far end of the Gulf of Finland.

Unlike warships, commercial vessels have no damage control systems; any damage will send them to the nearest port – assuming the vessel is still seaworthy. Damage which would be contained on a warship can get progressively worse on a merchant hull, leading to its loss. Commercial vessels are also subject to insurance expenses, which can skyrocket in conflict zones and may cause shipping companies to avoid transit of dangerous areas. Under the Hague convention, all mined areas must be declared, but not all declared areas must be mined. The hidden benefits of a stealth weapon have advantages because of the uncertainty – once a declared area is mined, all declared areas are mined. One explosion is proof enough for commercial entities. Not only does an individual mine not have to function to be effective, it may not even have to be emplaced to be effective.

Skipjack Quickstrike J loading in a B-1B during Valiant Shield 16 (Image by PACOM)

There are tactical benefits from closing access to a submarine pen or damaging the occasional warship. There are strategic benefits from interrupting access to war materiel, interdicting maritime transport, and inhibiting the movement of surface vessels. In an anti-access environment where the ability to penetrate deep into protected airspace is questionable, the Enhanced Quickstrikes offer a cost-effective, persistent threat that is difficult and time consuming to counter. In a globalized world, the new mining capabilities offer a significant asymmetric advantage for the Joint Force – if used correctly.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions and taking part in 2.5 SAM kills over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Colonel Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of U.S. Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the US Government.