The Islamic State (ISIS) is gaining momentum in India. By taking a greater role in the global fight against ISIS, India can prevent the extremist group from taking a stronger hold over its Muslim population, and make it more difficult for radicalized Bangladeshis to carry out attacks. Combating ISIS also provides India with the strongest basis for continued progress on U.S.-India security cooperation under the Trump administration.

India faces an increasing domestic threat from virtual recruitment and self-radicalization, which has resulted in some Indians officially joining ISIS and fighting in Iraq and Syria. Also of concern is the external threat from Bangladesh’s rising extremist population and radicalized individuals from Bangladesh that might plan and execute attacks in India if ISIS were to grow larger in the region.

Though there may be natural limits on the Islamic State’s success in India (such as Indian jihadists being preoccupied by the Kashmir conflict), ISIS’s unique online media exploitation has allowed individuals and small groups to garner significant attention. Furthermore, there aren’t similar natural limits on the growth of ISIS in Bangladesh. The porous borders between Bangladesh and India and the rising tensions in refugee camps related to the Rohingya refugee crisis are particularly concerning.

Islamic State in India

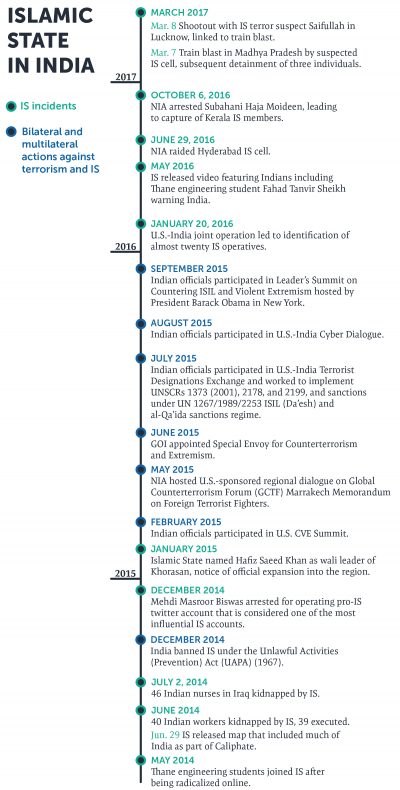

Although India’s Ministry of Home Affairs estimates that only 75 Indians have joined ISIS, the Islamic State is growing faster in India than many realize. Starting in 2014, cases surfaced of young adults trying to join ISIS online, without ever having face-to-face contact with a recruiter. In May 2014, a group of four Thane engineering students traveled to Iraq to join the group — one returned to India, two were killed, and one is still in the fight.

Although India’s Ministry of Home Affairs estimates that only 75 Indians have joined ISIS, the Islamic State is growing faster in India than many realize. Starting in 2014, cases surfaced of young adults trying to join ISIS online, without ever having face-to-face contact with a recruiter. In May 2014, a group of four Thane engineering students traveled to Iraq to join the group — one returned to India, two were killed, and one is still in the fight.

ISIS attempted to plant the seeds of unrest in India in June 2014 by including India in a map of its planned caliphate. Six months later, ISIS named former Tehrik-e-Taliban commander Hafiz Saeed Khan as the wali (governor) of the “Khorasan Province,” which includes India. Propaganda about Khorasan has not gained significant traction in India, however.

In December 2014, Bangalore police arrested Mehdi Masroor Biswas for operating the Twitter account @ShamiWitness, an ISIS propaganda account that was considered one of the most influential ISIS Twitter handles. Biswas had personally communicated with English-speaking members of the Islamic State and his account had international traction, including from one of the perpetrators of the July 2016 terrorist attack in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

In May 2016, the Islamic State released a video featuring Indians for the first time, including one of the Thane engineering student, Fahad Tanvir Sheikh, urging all Indian Muslims to join the movement to grow the caliphate into India.

The National Investigation Agency (NIA) raided a suspected ISIS cell in Hyderabad in June 2016 after discovering that the cell ordered explosive precursor chemicals. Interrogation reports indicate that ISIS planners had detailed knowledge of Hyderabad, and that they arranged for weapons to be delivered in a bag on a tree branch.

On March 7, 2017, a pipe bomb exploded on a passenger train near Kalapipal, Madhya Pradesh. Four suspects were interrogated and evidence from their computers suggests they were radicalized online. The following day, the Uttar Pradesh Anti Terror Squad engaged in a shootout in Lucknow with the terror suspect Saifullah, who they believed was a member of the Islamic State Khorasan cell.

In late April 2017, the Uttar Pradesh Anti Terror Squad and the Delhi Police Special Cell arrested three suspects from an ISIS cell, believed to be actively recruiting, and detained six others.

Almost half of the arrested ISIS members from India have been linked to a single online recruiter: Shafi Armar, also known as Yusuf-al-Hindi. Armar is a Karnataka native and is reportedly still alive and recruiting Indians virtually from Syria.

India’s Past Actions to Counter the Rise of Islamic State

India banned ISIS in December 2014, almost six months after UN Security Council Resolution 2170, which officially condemned the group and called member-states to take action against it. There are several possible reasons why India waited to put the ban in place, perhaps the most compelling being that ISIS held 39 Indian hostages (they were never released and have likely been killed). Although then-Defense Minister Manohar Parrikar said that India would fight ISIS under a UN resolution and a UN flag, the national government was quick to downplay his comments and maintained that this hypothetical situation would invite an evaluation of the situation, not necessarily action.

Indian government officials participated in a number of U.S.-led summits on extremism and ISIS during the Obama administration, though there was not high-level participation at the first meeting of President Donald Trump’s “Global Coalition Working to Defeat ISIS.”

Former Indian security officials cite the Intelligence Bureau’s (IB) Operation Chukravyuh as India’s main response to Islamic State’s growing online threat. Starting in late 2014, IB officers reportedly posed as Islamic State recruiters on Twitter, communicating with hundreds of Indian youth who intended to join the Islamic State.

After 21 Kerala natives left India for Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, the NIA launched an investigation into the high rate of Islamic State recruitment in the state, aided by the arrest and interrogation of Subahani Haja Moideen on October 6, 2016. Kerala is likely a hotspot for ISIS recruitment because some self-radicalized individuals who have joined ISIS and traveled to Iraq, Syria, or Afghanistan have returned to Kerala and recruited others. Additionally, the Indian Mujahideen (IM), a home-grown Indian terrorist group, has a strong presence in Kerala and after a known IM militant, Muhammed Sajid, was killed in Syria, the links between ISIS and the Indian Mujahideen became clearer. Both the IM and the Students’ Islamic Movement of India (SIMI), another radical Islamic organization with a strong presence, could help push already radicalized youth toward ISIS or serve as direct recruiting platforms.

India must grapple with the risk that if it plays a larger role in the global fight against ISIS it might become a target of increased attacks. Increased counter-ISIS measures both in India and on the global scale may add more “fuel to the fire” for radicalized individuals; in the May 2016 ISIS propaganda video, Fahad Tanvir Sheikh vowed to avenge the violence against Muslims in India and gave a formidable warning to India. India has only had one ISIS attack on its soil, which is remarkable considering its diverse population. However, the Islamic State is growing in India, and the train bombing in Madhya Pradesh in March and the detainments in Uttar Pradesh in April are signals that a policy change may be warranted.

India’s Potential Role in the Global Fight against the Islamic State

The anti-ISIS effort is one of Trump’s key foreign policy priorities, and the Trump administration will presumably be more willing to engage with other countries who have similarly made countering ISIS a priority. The Trump administration will likely criticize countries who are not supporting the U.S. coalition against the Islamic State; this could impact trade deals and other future negotiations. South Asia is critical in the fight against ISIS and India has the potential to play a large role in the United States’ regional strategy. To better collaborate with the United States on countering ISIS, India should consider conducting joint counterterrorism operations with the United States; sharing more inclusive intelligence, including updated terrorists watch lists; and taking a firm stance against Bangladesh’s weak response to terrorism.

As India has not been involved in the fight against ISIS on a global scale, there have been few opportunities for U.S.-India joint counter-ISIS operations. The CIA-NIA joint counterterrorism operation in January 2016, where the CIA reportedly alerted the NIA to a north Indian ISIS cell, was successful in capturing members of the cell, but it underscored a perception in the U.S. government that the critical information-sharing is a one-way street.

India can widen its information sharing network to include its complete, updated terrorist watch lists with the United States regularly. Although the 2014 Joint Statement mentioned identifying areas where terrorist watch lists could be exchanged, there has been no indication that this exchange has officially taken place and how frequently the watch lists would be updated.

Another potential point of contention between the United States and India is over Bangladesh. India supports Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her government, but, until recently, Bangladesh has been slow to act against ISIS. India’s strong support of Hasina’s government must be tempered by strong condemnation of its response to ISIS terrorism. India’s support of the Bangladesh government could open the door for coordinated ISIS attacks in the future, and for Bangladeshi ISIS fighters to make their way into India. India should align its approach to the Bangladeshi government with that of the United States and coordinate intelligence and information sharing appropriately.

ISIS poses a significant threat to India, but India has not been engaged in the global fight against the group. Virtual self-radicalization is a growing problem and it might quickly escalate, possibly into kinetic attacks. If India becomes more involved in the global fight against the Islamic State by working closely with the United States in the region, sharing terrorist watch lists, and taking a stronger stance against Bangladesh, it can have a stronger partner to fight the growing domestic threat of ISIS while making a global contribution that Trump will likely value.

Natalie Tecimer is a research associate and program manager with the Wadhwani Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. She tweets at @NatalieTecimer.