China’s foreign non-governmental organizations (NGO) law has been in force for half a year, since January 1, 2017. Under the law, any not-for-profit, non-governmental social organizations lawfully established outside mainland China, such as foundations, social groups, and think tank institutions, should register with the Ministry of Public Security, or the police, before conducting any activities within mainland China. (Ironically, groups from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, also counted as “foreign,” should comply with the law, too.)

China has never released any official data on the exact number of foreign NGOs operating in the country before the NGO law was issued. The closest we have to an official number was mentioned once by Fu Ying, former vice foreign minister of China. When talking about the foreign NGO law during the fourth session of the 12th National People’s Congress on March 4, 2016, Fu revealed that “there are more than 7,000 foreign NGOs operating in China.”

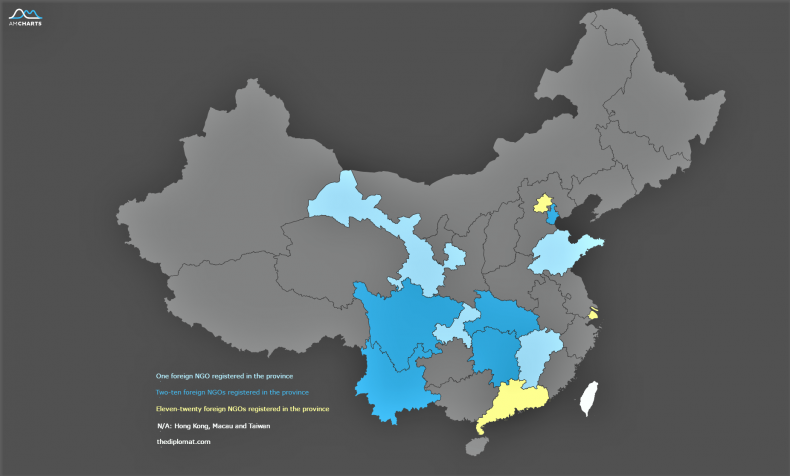

So how many foreign NGOs out of these 7,000-plus have successfully registered so far? Based on public information, The Diplomat has confirmed only 91. Beijing has approved 20 foreign NGOs, the most nationwide. (Check out the entire list in text form, with sources, here.)

On April 1 (April Fools’ Day), China’s government-run Xinhua News Agency published an article claiming that “the foreign NGOs believe the registration procedure under new law is more convenient, efficient, and simple.” The article confirmed that by April 1, 62 foreign NGOs had legally registered in China. Interestingly, it also acknowledged that more than 780 foreign NGOs have consulted with the police on registration.

Now it is still uncertain what is happening to the majority of foreign NGOs operating in China: have they decided to wait to see, or to leave, or not to register at all, or they have actually applied for registration but got no reply from the Chinese police?

Yet at least one thing is for certain: those organizations that haven’t received official approval are supposed to stop operating in China, technically speaking. Otherwise, they would face on-site inspection by police, examination of documents, the freezing of their bank accounts, sealing of venues, seizure of assets, temporary or permanent suspension of activities, and staff members’ detention, according to the law.

Last Updated: June 5, 2017