This report is based on data gathered and analyzed by students from the American University of Central Asia (AUCA)’s Department of Journalism and Mass Communications (JMC): Malika Alimbaeva, Aizhan Amanova, Erlan Arunov, Belal Ataee, Kamila Baimuratova, Beksultan Bekenov, Aidai Chekirova, Arina Efranova, Kamila Eshalieva, Parwin Faizi, Razia Gul, Meerim Jetenbaeva, Samat Jumakeyev, Rustam Khalimov, Diana Khan, Tatiana Kim, Anastasiia Laskina, Suraya Mirzada, Sosan Mohammad, Anisa Noori, Sonya Navruzova, Malina Sadiqi, Naquibullah Sarwary, Farkhunda Sadiqi, Zarlasht Sarmast, Talgat Subanaliev, Aizada Sydykova, Corinna Vetter, Daria Taalaibek-kyzy

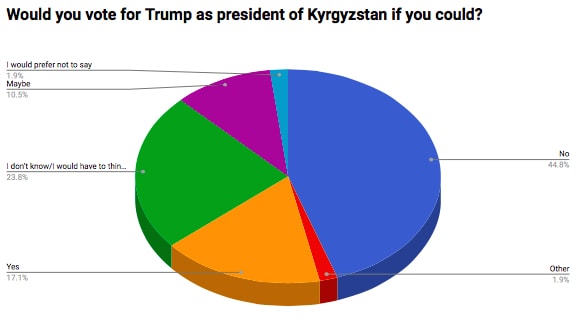

When young, educated voting-age dwellers of Bishkek were asked by their peers this past spring whether they would vote for Donald Trump if they could in Kyrgyzstan’s upcoming presidential election, nearly 45 percent said they would not – but 51 percent expressed more or less openness to the idea.

This was the surprising finding from a public perceptions poll about the United States’ new president conducted during the Nooruz holiday by my students at the American University of Central Asia (AUCA)’s Department of Journalism and Mass Communications (JMC).

The poll did not only engage in this thought experiment. It also explored young people’s feelings about Trump’s presidential campaign promises, his policies since becoming president, and their sense of the potential impacts upon Kyrgyzstan of rapprochement with Russia and a “Muslim ban.” My students also tried to get a sense of respondents’ media habits.

We thought Kyrgyzstan would be a unique context for such a poll because of its status as a society that is simultaneously part of the Islamic, Russian-speaking, and democratic worlds, and which is also a major net exporter of migrant labor to Russia, Turkey, and the West.

A Poll of Kyrgyzstan’s Millennial Generation

The poll was collaboratively designed by the 29 students of my “News-Writing Skills II” and “Investigative Journalism” courses, which they then conducted across Kyrgyzstan’s capital city during the AUCA Spring Break, which occurs during the third week of March. It took the rest of the semester and part of the summer to process and analyze the results.

Our pool of 106 respondents could be said to be representative of Bishkek’s young and educated middle class. The majority (64.8 percent) claimed that their propiska (municipality of residency) was from Bishkek itself. They were largely female (58 percent) with an average age of 28.7 and a median age of 22. A whopping 82 percent had some level of education beyond secondary school.

In terms of employment, although 33 percent were students at the time of their interview, 22 percent were working in more or less white collar jobs, including serving in the government and in the civil society sector, while another 11 percent were unemployed.

Trump’s Signature Issues Divide Young Kyrgyzstanis

Respondents seemed generally knowledgeable about Trump. Regarding his career before politics, it came as no surprise that the majority (71 percent) knew him as a businessman. When asked what they believed to have been his presidential campaign promises, most respondents (64.3 percent) appeared able to give more or less factually accurate descriptions, with the border wall between the United States and Mexico the most prominent (16.5 percent).

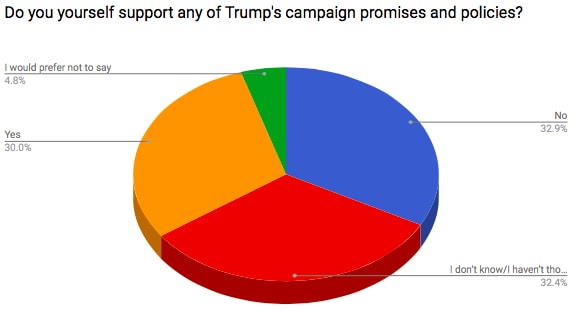

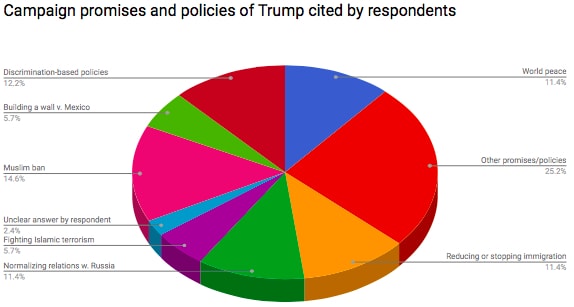

When it came to the question of whether there were any campaign promises or policies made by Trump that they themselves supported, the overall pattern was of division and uncertainty: 37.2 percent expressed either uncertainty (“I don’t know/I haven’t thought about it”) or reticence (“I would prefer not to say”) on the question, while nearly 33 percent said no and 30 percent said yes. Despite this divergence in support levels, for all three groups the same three policies were cited most often: Trump’s campaign promises to institute a “Muslim ban,” reduce or stop immigration into the United States, and normalize relations with Russia. At the very least, this demonstrates solid knowledge among Kyrgyz youth about Trump’s signature ideas.

Hopeful About Rapprochement With Russia, Uncertain About Muslim Ban

Respondents tended to have strong reactions to Trump’s stated feelings about Russia and Islam, as reticence was low: 62 percent and 75 percent of the time they were willing to express an opinion, respectively.

With respect to Russia, although 58 percent assessed that Trump’s feelings about the country are generally positive, they were divided as to whether his feelings are accurate, with nearly half (47 percent) generally agreeing versus another nearly half (49 percent) who felt the reality of Russia is more complicated.

Nonetheless, were Trump to succeed in effecting a rapprochement with Russia, a majority (58 percent) believed there could be an impact upon Kyrgyzstan due to Bishkek’s connections to Moscow. A quarter of respondents expressed a feeling of “dependency” on the part of Kyrgyzstan toward Russia, while others were less despondent, invoking current partnerships in regional projects such as the Eurasian Economic Union (22.5 percent) or the two countries’ shared Soviet past (8.8 percent).

With respect to Islam, a striking 83 percent assessed Trump’s feelings about Islam as generally negative, with 61 percent deeming his feelings as generally inaccurate. Nonetheless, 21 percent expressed uncertainty, while 18 percent deemed his feelings generally accurate.

Opinions were divided about whether Trump’s feelings about Islam could impact Kyrgyzstan. Approximately 44 percent felt so, but a quarter chalked it up as “unknown.” When analyzing the respondents’ explanations, we noticed two interesting patterns. Seven times Kyrgyzstan was described as either “not really Muslim” or “Islamic but secular and democratic,” and nearly 12 percent of respondents pointed out the lack of a clear incentive for the United States to target the country.

Russian Media Appears Not as Dominant as Predicted

Where did respondents get their information about Trump? Despite expectations that Russian state-sponsored media would dominate results, we were surprised to discover that respondents prefer local news outlets by a tremendous three-quarters.

However, there was no clear victor in terms of specific outlets. The website Zanoza.kg came in first place at 15 percent and Russia’s Perviy Kanal in second place at 13 percent, followed by Kloop.kg and Akipress.kg at 11 percent each. It is perhaps no surprise that websites would be the preferred source for the young.

Respondents claimed by as much as 40 percent to be interested in political and economic news, and slightly over half (53 percent) claimed to prefer international news. However, we suspect that respondents may have been tailoring their answers to these questions because of the nature of the poll.

My students and I are still trying to understand what exactly is happening in terms of respondents’ information habits. One student performed a content analysis of reporting about Trump in local media. She has found a mix of accurate and inaccurate reporting, slightly leaning toward the latter.

“Kyrgyzstan needs a rich and wealthy president who will not steal [our] money…”

As for the thought experiment, although nearly 45 percent were adamant that they would not vote for Trump if they could, approximately a quarter (23.7 percent) said they would need to think about it first, while another 17.1 percent said they would and 10.5 percent said “maybe.” Of the entire poll, this was the most striking result, as we interpret these numbers to mean slightly more than half (51 percent) are more or less open – or at least, not closed – to the idea.

When we dug deeper into respondents’ explanations, we found some interesting things. Several emphasized his credentials as a businessman both as a negative and a positive attribute. Some were worried about his apparent radicalism, while others interpreted this as patriotism.

“I think Trump is very clever and a patriot of his own country. If we could have such president, our country would develop.”

“If he would protect Kyrgyzstan as he is doing with the U.S. then maybe I would.”

“Everyone loves their country. If my president would say, ‘I will fix everything, and I will give you a job,’ of course I would vote for such a person.”

“Because Kyrgyzstan needs a rich and wealthy president who will not steal the money of the government and the people.”

“Kyrgyzstan needs a true leader who sets the well-being of its citizens first.”

However, a theoretical Trump campaign in Kyrgyzstan would face serious stumbling blocks, ranging from his negative feelings about Islam to his aggressive persona. Several times respondents described “the Kyrgyz people” as “not radical.”

A Grain of Salt Is Needed

Because we wanted to understand respondents’ feelings and factual knowledge about Trump, we permitted free-form answers to some questions. Consequently, it took a while to categorize the data, and we knew that some of our choices would be rough at best.

We chose not to ask for people’s ethnicity or religious affiliation. Demographic questions can be highly sensitive in Kyrgyzstan; even asking for someone’s propiska can raise an eyebrow. Unfortunately, this meant that we could not conduct a proper cross-sectional analysis. For instance, did ethnic Kyrgyz Muslims disagree with Trump’s feelings about Islam more than ethnic Russian Christians? That is an important question that we were unable to answer with this poll.

Originally, my students had set out to conduct a comprehensive survey, one whose sample pool would be representative of Kyrgyzstan as a whole. However, it became clear only during analysis that the survey was representative of those born and educated since independence.

Approximately 29 percent of the time, respondents preferred not to give an answer or opinion to our questions whenever given the option. For the purposes of content analysis, we needed to filter out such non-responses to understand the dynamics of those who did provide answers. However, that so many respondents were reticent is a potentially significant hole in the data.

Finally, we made some mistakes in the design of range-based questions. For instance, when asking people whether they would vote for Trump as president of Kyrgyzstan, we allowed respondents to choose “Maybe” or “I don’t know/I would need to think about it.” It would probably have been better to have offered them “Maybe/I would need to think about it” and “I don’t know.”

All told, our findings probably should be taken with a grain of salt.

Maybe Millennials Around the World Do Not Hate Trump

Nonetheless, one of our poll’s most important measures indicates that the salt grain need not be a large one. Near the beginning and near the end of every interview, respondents were asked to provide single-word adjectives describing Trump. Both times, negative adjectives not only outweighed positive ones, but remained steady: 44.8 percent versus 36.2 percent at the start, and 42.9 percent versus 34.3 percent at the end, respectively.

That our young, urban, and educated respondents’ feelings about Trump were not significantly affected by the process of thinking through his campaign promises, feelings, and potential impact upon the world suggests a degree of reliability in our findings.

The adjectives ranged from the superlative – spectacular, hysteric, imperious, clownish – to the colorful – merry, strange, frivolous, infantile – to the derisive – vredniy (adversarial), khitriy (foxy), umniy (clever), pediatr (literally, child doctor). Positive adjectives included concepts such as hardworking, presidential, confident, purposeful, enterprising, and normal’niy (normal/proper); while negative adjectives included concepts such as showman, inexperienced, indecisive, cruel, and selfish. Some frequent adjectives were ambiguous, sometimes indicating positive feelings and sometimes negative feelings, such as businessman, rich, and unpredictable. (We have prepared a pdf of all the adjectives and our analysis of them for readers. Please click here.)

All told, although we found that negative feelings were more often definitively expressed by respondents than positive ones, underlying patterns suggest something more complex: the notion that the younger and more educated a person, the less positive his or her opinion of Trump – and possibly also of other political figures like him – may not hold true in Kyrgyzstan.

In other words, the idea that there is a direct relationship between one’s status as a millennial and one’s dislike of Trump may be a phenomenon specific to Western societies (and there is debatable evidence that suggests this is a stereotype even in the West).

Christopher Schwartz is a journalist based in Kyrgyzstan. He also teaches journalism at the American University of Central Asia.