In 2006, Malaysian antropologist Aihwa Ong’s Neoliberalism as Exception was first published. The text soon became a reference book to all of those interested in the hybrid forms neoliberalism can manifest in around the world. One of Ong’s main arguments was that Asia, and particularly post-Mao China, had been successful in taming the neoclassical economic doctrine while subjecting market agents to a very selective state-controlled regime of free market dynamics in the region. The outcome was a condition of “graduated sovereignty and citizenship.”

In other words, Asian states would deliberately allow for some neoliberal “exceptions” to a firmly state-centric mode of politico-territorial governance. For example, Beijing still maintains the upper hand when it comes to deciding who will play the capitalist game inside the territory – and the example of Google possibly is the most telling in this regard.

A decade ago, when Ong was writing her book, China and Southeast Asia were striking as role models for the future, whereas Japan and South Korea were already considered established powers for every practical matter. Some of the elements leading to Ong’s set of conclusions could – and can – be clearly seen in Taiwan and Hong Kong, then and now. In the former, the idea of representative democracy and liberal capitalism making an inseparable match has become rooted in less than two decades. In the latter, financial deregulation was deepened by the increasing acknowledgment of China’s renminbi as a reliable and globally tradeable currency.

Another interesting feature of Asia’s “neoliberalism as exception” over the last ten years concerns the manner in which China, Japan, and South Korea have organized their own high-tech industries in order to benefit the most from global value chains. In comparison with American and European companies, Asian businesses are far more verticalized and closed in their relationship with worldwide suppliers, usually buying raw materials and manufactured parts from local producers rather than foreign ones – thus applying a kind of protectionist spin. A quick approximation between the industrial cycles of two electronics giants, Apple and Samsung, would drive home the point.

In a sense, all the progress reported lately by feminist movements and NGOs in Japan and South Korea also connects with the advancement of this neoliberalism-as-exception approach. While cultural and religious factors may hamper and prevent women from joining the marketplace on an equal footing with men – since they are still under strong social pressure to play traditional feminine roles – the rising influx of domestic workers (not to mention sex workers) from poorer countries in Southeast Asia – mainly Thailand and Vietnam – help to free women who belong to the middle and upper classes from activities strictly related to housekeeping and child rearing. However, there is heightened concern today as to whether these new realities in Asian liberally oriented economies will do harm to the social fabric.

Higher Education: The Next Frontier

Neoliberalism as exception also appears to be growing stronger at academic venues. Japan and South Korea were educational laggards in the 1950s (when less than 10 percent of their respective populations had access to higher education), but have spectacularly implemented an ambitious plan with a view to make their nationals enroll in higher education courses. The bottom line of those initiatives, taken in the early 1960s, was very impressive: By 1990, while around 42 percent of all Japanese citizens had been taking courses and earning their university diplomas, roughly half of the South Korean population were being (or had been) schooled at the university level. That was a revolutionary move under every respect.

Unsurprisingly, the educational shifts in current times come from India and China. New Delhi aspires to have some 30 percent of its huge population enrolled in higher education by 2030. For that, massive investment in R&D, especially in the field of information technology, is a shortcut envisaged by the Indian government to catching up with the best and the brightest. Meanwhile, Chinese elite universities – such as Peking, Tsinghua, or Fudan, to name just a few – can already claim membership to a very exclusive club, as they are ranked among the top 100 in the world. The higher education budget is surging and will soon make up 2 percent of China’s annual GDP.

The beauty of Asia’s educational drive lies in the way Asians absorb cutting-edge knowledge from Western academic bastions – the so-called Ivy League institutions, which receive thousands and thousands of Indians, Koreans, and Chinese students yearly – and adapt such ideational contents to their national/regional backgrounds. This tendency has everything to do with neoliberalism as exception: selectively grasping techniques and information for a given purpose, but without relinquishing the local and/or cultural strings. Just look at the way adaptive think tanks – a most typical Western invention – have blossomed in China and India lately, and you will realize the extent and depth of this unique Asian contemporary phenomenon.

Confucius Meets Ronald McDonald

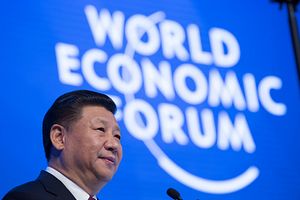

Earlier this year, Xi Jinping delivered a speech at the World Economic Forum in Switzerland which captured headlines and sparked much controversy, being interpreted as an ode to economic globalization. Xi’s case for free trade sounded like music to the ears of old-school Westerners in North America and Europe. As a consequence, many global media outlets – including The Diplomat – asked: Has China ultimately gone liberal?

I’m afraid not. American political scientists Peter Katzenstein and Nicole Weygandt provide an insightful take: While Chinese cosmovision is often associated with Tianxia – the concept according to which China enjoys centrality in the universe – the US perspective about the world we live in can hardly be detached from neoliberalism – or, should one prefer another label, utilitarian thinking. Please note that there might be full compatibility between one viewpoint and the other. Confucius can meet Ronald McDonald these days, but such an inter-civilizational encounter would be tactical and contingent rather than existential and transformative. At the end of the day, China or Asia may stand exactly where they are. This is – so I argue – what the Asian exceptional neoliberal experience is all about.