In late July, rumors broke that the Indian Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) had blocked a proposal by a Chinese conglomerate, Fosun International, to buy 86 percent of Indian drug manufacturer Gland Pharma. The block was instantly described as a byproduct of the ongoing stand-off between Indian and Chinese forces on a Himalayan plateau claimed by both China and Bhutan. A closer look at the deal suggests that India’s concerns predate the stand-off and that India, like other countries with increasing exposure to China, is struggling to find a happy medium between much-needed investment and overexposure to China’s economic woes.

The Fosun/Gland deal, first announced in late July 2016, was described as the first case of a major Chinese investment in an Indian manufacturing firm. It has shown signs of trouble since long before the Doklam stand-off began. India’s policy on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the pharmaceutical sector required that investments of more than 74 percent in existing companies be approved by the Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) (this body is now defunct; the Fosun/Gland deal was one of the last cases it reviewed). The FIPB deferred decision on the proposal for two consecutive sessions, unusual although not unheard of; earlier reports suggested that the FIPB’s reluctance to take up the proposal was due to the objections of the Home Ministry. Finally, at the end of March 2017, the FIPB pushed the proposal to the CCEA. This step was not administrative; the FIPB has full power to approve proposals involving investment of less than $785 million, and Fosun’s was listed at $675 million.

The CCEA is an opaque body. At least one government official denied that the CCEA had even reviewed the Gland proposal, much less rejected it, and the lack of public minutes make it hard to know for certain. Comparisons to the CCEA’s usual practices suggest that the proposal is in trouble, however. Between December 2015 and its final meeting in April 2017, the FIPB referred 9 proposals to the CCEA, five of which fell below the $785 million threshold for automatic referral. Five of the nine have since been approved, all within roughly three months of referral. The cases that have met delays, not including the Fosun/Gland deal, are generally smaller proposals that are highly complex or that touch on new points of FDI policy. None involve a large-scale acquisition of an Indian company by a fully foreign entity.

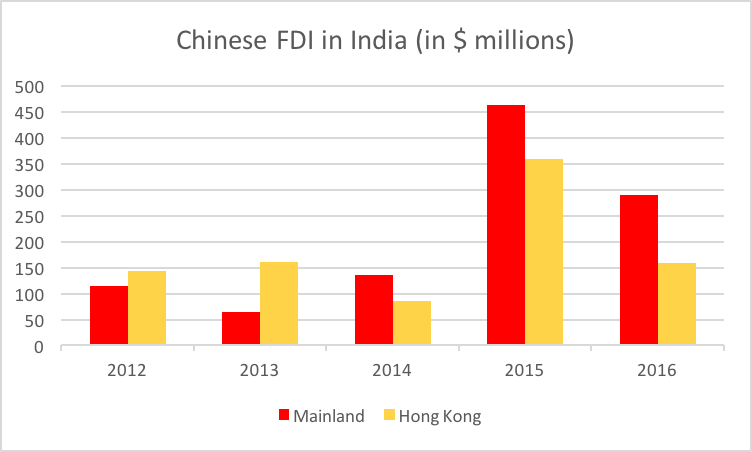

Part of the difficulty of evaluating the significance of the hold or block on the Gland acquisition is that it is such an unusual event. Indian statistics on Chinese investment show significant but not consistent growth. Investment from China spiked in 2015 after a period of stasis but fell again in 2016. (Additional Chinese investments are likely routed through Singapore or Mauritius, the official top source countries for FDI into India thanks to their favorable tax treatment.)

India’s pharmaceutical industry, which has gained fame as a generic drug supplier to the world, is a surprisingly sensitive sector for Indian regulators. But it’s also possible that the CCEA is less concerned about the target than the acquirer. Fosun is one of a group of high-profile Chinese conglomerates that have recently fallen on hard times. These so-called “grey rhinos” have amassed so much debt that they may threaten the Chinese financial system, particularly its state-run banks. Fosun is politically exposed as well; the company’s chairman, Guo Guangcho, was briefly held by police at the end of 2015, apparently to help with an anti-corruption investigation. As part of an effort to reduce their debt load, the Chinese government has been leaning on the grey rhinos to walk away from pending deals; it’s possible that the Gland acquisition could become a casualty of this approach even if CCEA gives its approval. Some of India’s Asian neighbors are beginning to question the wisdom of selling assets to Chinese companies enmeshed in debt, even if they lack strategic value.

Despite the relatively small presence of Chinese firms, their investments attract disproportionate attention in the media and from state-level Indian officials. As I wrote last year, cooling relations between the Indian and Chinese governments don’t stop state officials from courting Chinese business. These junkets and meetings have continued apace. Haryana is considering a joint venture with Dalian Wanda to build shopping malls; Andhra Pradesh is courting Chinese investment in its new capital; SAIC is reviving the former General Motors plant in Prime Minister Modi’s home state of Gujarat. Part of the attraction for state leaders may be Chinese investors’ willingness to pledge enormous sums, such as a commitment by now-disgraced technology company TEB Technology to invest $4.3 billion in West Bengal. In the hyper-competitive race among states to pull in the most investment pledges, empty promises have their own value.

India needs investment, whatever the source. Sino-Indian economic relations show promise and are a welcome offset to security tensions between the two countries. But countries around the world are re-thinking their previous openness to unfettered investment. In this respect, India may be ahead of the curve.

Sarah Watson is an associate fellow in the Wadhwani Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). She tweets at @SWatson_CSIS.