Spoilers for Wolf Warrior 2 to follow.

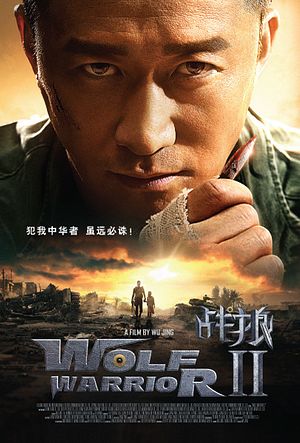

As the jingoistic, action-packed Wolf Warrior 2 (Zhàn Láng 2; 战狼2) advances closer to $1 billion in global box office receipts, it appears China has found — as Rance Row, a prominent Asian film consultant, says — its “Rambo.” Yet, box office receipts don’t tell the whole story, Warrior also blew away another Chinese movie metric: it exceeded box office receipts for a movie during the non-Chinese New Year period, a traditional movie-going period akin to the holiday season in America. It would seem Warrior’s success surpassed even its own previous expectations: the first installment, Wolf Warrior (Zhàn Láng; 战狼), netted $88 million in 2015. In an interview with Variety, Row remarked that “this is definitely an important event.”

As BBC’s Beijing bureau points out, Warrior auspiciously debuted a few days ahead of the People Liberation Army’s massive 90th anniversary celebration and parade and on the same day as the state-sponsored film, The Founding of the Army (Jiàn jūn dàyè, 建军大业). Even though Founding, a historical drama that chronicles the formation of the PLA, is packed with pop star cameos, it received a lukewarm reception by Chinese audiences. Why the disparity? Perhaps, Founding’s propaganda-esque feel deterred Chinese viewers. State media does enjoy an essential monopoly over film production for some time. There could be other, alternate reasons for Warrior’s success. China’s has banned or limited the release of imported movies. Hollywood is accustomed to jockeying each year for one a few coveted spots for imported films in Chinese theaters, essentially corralling viewers to homegrown flicks. Moreover, Chinese movie houses have been involved in ticket-sale scandals where they bought their own tickets to inflate sales or puff cinema statistics. But this is not the case here; the audience’s enthusiasm is real and there is a genuine desire to see Warrior.

Wolf Warrior vs. Rambo

The Warrior franchise follows Jing Wu, an ex-special forces sergeant, as he takes on a vicious drug lord bent on exacting revenge (Warrior 1) and a gang of evil, violence-wielding Western mercenaries in Africa (Warrior 2). Warrior’s huge success augurs a Chinese appetite for more assertive Chinese military heroes and, possibly subconsciously, for a more assertive PLA. While patriotic war movies are not new to American movie goers, Warrior has struck a chord with Chinese audiences ambivalent of hackneyed, party-sponsored films. This will likely be the start of a growing trend in the military action film genre. Be prepared for more Warrior and Warrior-like flicks to come. But first, why the Rambo analogy?

If the arts do in fact reflect society then the Rambo simile by Row is even more telling with emerging Chinese perceptions of its modernizing military. Indeed, a generation of Americans were raised on Chuck Norris’s Delta Force and Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo movie franchises, among others. Specifically, the 1980s Rambo trilogy focused on three movies: Rambo: First Blood, Rambo: First Blood Part II, and Rambo: III. For those unfamiliar with the Rambo movies, essentially the stories follow an ex-Vietnam special forces, John Rambo, with his action-fused adventures both at home and abroad in Vietnam and Afghanistan. The Rambo movies’ personified America’s ability to accept its Vietnam veteran community and misadventure in Vietnam and even for the direct smack-down, confrontation that Americans longed for against their Cold War adversary, the Soviet Union. Combined, the first three Rambo movies grossed over $600 million worldwide, big by 1980 box office standards, but a drop in the bucket compared to Warrior 2’s success thus far.

Roll Credits

Just as this writer watched action-packed war movies growing up, generations of Chinese watched Maoist and Party propaganda films celebrating China’s defeat over Japan or America’s supposed defeat against North Korea. As the Oxford Handbook on Chinese Cinema notes, one of the more popular ones was the flick Shanggan Ridge based on a Chinese unit repelling waves of American attacks in Korea. But noticeable changes are already underway in other Chinese media genres: TV programming and documentaries. Once a taboo topic, the Korean War or The War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea reemerged last year on a Chinese television series. 38th Parallel chronicles two Chinese fishermen that survive an American attack in 1950 on the Yalu River and then decide to fight as volunteers alongside the North Koreans. Meanwhile, the documentary Twenty Two (Èrshí’èr; 二十二), released within a few weeks of Founding and Warrior, follows 22 Chinese women forced as comfort women for the Japanese in World War II. It brought in over $18 million – making it the highest grossing domestic documentary ever in China. The Warrior films may reflect a broader resurgence of the PLA and reversal of previous Chinese humiliations in popular culture.

Either way, Warrior syncs not only with Chinese economic and political aspirations, but also military ones as well. While the movie is silent on any mention of the Communist Party or Chinese leadership, the plot highlights economic and political cooperation in Africa, a trademark of the One Belt One Road. The movie is set in a fictitious African nation and a status of forces agreement would ostensibly exist for the Chinese military operating there. More germane to China military analysts, cameos of new military technologies and techniques are sprinkled throughout Warrior. Viewers can’t miss the obvious bow to traditional martial arts in multiple, close quarters fight scenes between Wolf Warrior and Big Daddy, played by Frank Grillo as the Western-stylized mercenary ringleader. The inclusion of armed drones by the mercenaries, the PLA Type 99 battle tank, and synchronized long-range fire support from a PLA-Navy warship is a more subdued nod to an increasingly expeditionary, modernized, and maritime-focused PLA, noted in the 2015 Chinese Military Strategy white paper. Moreover, mission themes sprinkled in the plot include scenes of Chinese non-combatant evacuations, anti-piracy operations, and civilian peacekeeping that mirror real-life, non-fictional missions. China evacuated over 35,000 nationals from Libya in 2011 as it descended into chaos, provides UN peacekeepers in a variety of hotspots in Africa, such as South Sudan and Mali, and continues to support anti-piracy missions along the Horn of Africa.

In light of recent border tension with India at Doklam, militarization of its “terriclaims” in the South China Sea, and the unveiling of its new and first forward military base in Djibouti, an ascendant China sharing the screen with Wolf Warrior 2 does not seem that farfetched. As mentioned earlier, if art does reflect society, then it appears the Chinese are leaning not only into a Wolf Warrior that is responsive, globally-focused, and bent on protecting Chinese nationals and interests, but also a People’s Liberation Army that is as well. As the Chinese blogger Chublic notes, “To some extent, the whole movie can be seen as a convenient set-up to show off the might of a rising superpower.” The movie concludes with a fight scene between Wolf Warrior and Big Daddy in which Big Daddy goads Wolf Warrior that “People like you will always be beaten by people like me. . . Get used to it.” The Wolf Warrior replies “That’s history” and kills the antagonist with a round of fatal jabs. It seems Chinese viewers are keener for where China’s military is going rather than where it has been. Anticipate the Wolf Warrior 3 trailer in theaters soon.

Wilson VornDick is a Commander in the Navy Reserve and previously served at the Chinese Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College and studied in China. These are his personal views and are not associated with a U.S. government or U.S. Navy policy. He tweets at @vorndick.