News reports over the past few months paint a bleak picture of the state of democracy in Asia. In Cambodia, a severe crackdown on political dissidents has been imposed by the prime minister and the closing of the last independent newspaper suggests that democracy is crumbling well before next year’s general elections. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte’s anti-drug crusade has led to thousands of victims in a spate of extrajudicial killings. In India, civil society has called on the government to address the shrinking civil space and ensure that people are given appropriate voice. And in Myanmar, one of the international community’s most prominent defenders of democracy and human rights, Aung San Suu Kyi, has received harsh criticism from around the globe for failing to act on the ongoing Rohingya crisis.

However, the bigger picture actually tells another story. Over the past ten years, net democratic progress has increased significantly. Democratic gains have surpassed the rollbacks and the agenda for “government of the people, by the people, for the people” is gaining momentum.

Net democratic progress – surpassing other regions

Quantitative measures can help us see the forest rather than just the trees. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Democracy Index as one of these measures provides evidence of democratic progress and backslides building on key dimension such as electoral processes and pluralism, civil liberties, the functioning of the government, political participation and political culture.

According to the EIU Democracy Index, when comparing the level of democracy, measured on a 10 point scale from 0 (authoritarian) to 10 (full democracy) over the past ten years, the average democracy score in Asia has increased from 5.05 in 2006 to 5.41 in 2016. Matching global figures – for both years – were 5.52. Thus, while the world seems to have been on a standstill, Asia has been moving forward. Net democratic progress is surpassing all other regions around the globe.

Progress in south and southeast, stagnation in the east

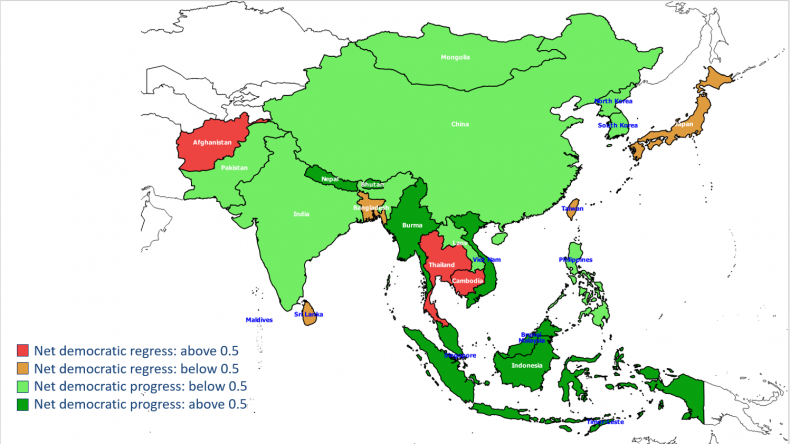

At the same time, sub-regional variations are significant. Whereas solid democratic gains are recorded in South (0.62) and Southeast Asia (0.50), East Asia is experiencing stagnation (0.02).

Some of the most prominent gains made are worth mentioning. In Nepal, the democratic movement swept the country as the peace agreement between the government and the Maoists insurgents was signed, and royal powers were replaced with a republic over just a few years. Elections were organized and in 2015 a new federal constitution was put in place. In Bhutan, the absolute monarchy was substituted by a constitutional monarchy and a new democratic constitution was put in place, followed by the country’s first elections in 2008. In Myanmar, the military government has gradually conceded space to democratic reforms, culminating in the organization of multiparty elections in 2015 – the first of its kind in the country in the last 20 years. Significant achievements were also recorded in countries like Timor-Leste, Vietnam, Indonesia and Malaysia over the past decade.

On the other hand, South and Southeast Asia also hold the three countries with the most democratic regression. In Thailand, the military coup of 2014 and much-delayed elections have put the democratic project in jeopardy. Cambodia started out already at a low level but has nevertheless slipped even further. And following a period filled with hope after the 2004 elections, Afghanistan has experienced another strong backslide.

Compared to this, East Asia is experiencing total stagnation. In other words, net change – positive or negative – is close to zero. South Korea and Japan represent the two countries with the most advanced democracies, but neither has been able to make additional progress over the past decade. North Korea remains at the bottom of EIU’s Democracy Index list of countries – not only in Asia, but also globally. Whilst very modest, net progress is actually highest in China, much thanks to its ability to deliver effective governance.

Five areas to watch for continued advancement

Regional trends hold the keys to the success of the democratic movement. Here’s a roundup of five key elements that the democracy movement must watch out for in the years to come.

Safeguarding pluralism

Politics in Asia must set the bar high when it comes to accounting for pluralism. Ethnic and religious as well as caste or clan systems form the basis of most societies in the region, but allowing the politicization of such divides puts democracy (and ultimately stability) at risk. Over the past months, we have witnessed growing concerns around the abuse of religion to advance political agendas. Such developments must be met with not only inclusive laws that ensures the rights and fundamental freedoms of all regardless of identities, traits and different opinions, but also strict enforcement. Political leaders cannot linger on this matter, nor remain silent when abuses take place.

Cultivating democracy from the bottom up

Democracy in Asia must be able to deliver in order to gain support for the democratic project “from below.” It must demonstrate the ability to pay off. While rarely hitting international news, the advancement of local structures – that are closer to local challenges, better equipped to identify local solutions and easier to hold to account by citizens – is vital. In Nepal, federal structures have recently been put in place as per the new Constitution. The degree to which it will succeed in pushing service delivery and enhancing citizens’ inclusion in decision-making and thus demonstrate democratic dividends will depend on how the delegation of powers – and, importantly, delegation of discretionary financial resources – are put into practice. Through dividends, a democratic culture can be nurtured and expanded.

Building on technological innovations

Internet and social media have expanded information sharing around the globe and dramatically changed the political scene. In the coming years, these developments will strongly influence political life in Asia. It will affect how political parties work internally, how they are financed, how they communicate with party cadres, and how they connect with electorates in campaigning for office. It will also help civil society to hold politicians to account. Such communications technology provides opportunities for civil society to tack and monitor campaign promises, service delivery, and financial flows in politics and communicate their findings with the broader public. How various actors are able to use new tools to effectively – for parties and politicians to consult and engage will with citizens and for watchdog organizations to take action to promote transparency and accountability – will be key to progress. While the Asian region has an active social media penetration of 47 percent compared to 37 percent for the world average, Freedom House findings on internet freedoms in the region, only one out of 14 countries scrutinized was given the thumbs up. This is a steep hill to climb.

Beyond internet and social media, technological innovations in public management are also worth noting. For example, the organization of electoral processes are increasingly run by the use of technological systems. In using high-tech solutions, the establishment of secure systems that nevertheless operates with significant transparency will pose a challenge. Handled with care and ensuring broad acceptance across political and social divides are necessary for tech solutions to advance the democracy agenda in the region.

Capitalizing on growing cities

The attraction of cities to realize the potentials of the citizens is here to stay. Together with Africa, Asia is urbanizing faster than other global regions and the urban population is estimated to increase from 48 percent today to 68 percent by 2050. In other words, seven out of ten will live and work in the cities. Nearly half of Mongolians live in Ulaanbaatar. Urbanization and emerging mega-cities are going to pose a huge challenge in terms of infrastructure and climate but are, in many countries, considered a vehicle for economic growth and hence development. What is less evident is how such urbanization may push the democracy agenda forward, i.e. how cities will smooth coordinated citizen actions, increase democracy demands and stimulate civic capital. The ability of the democratic movement to seize and capitalize on these opportunities will affect its success.

Benefiting from youth

The growing youth population is – if treated with care – presenting a unique opportunity for advancing the democratic agenda. In countries like Bangladesh and India, young people account for around 20 percent of the total population whereas in East Asia the population is aging. Bringing youth energy and creativity into politics will spur new thinking and innovation. They are tech-savvy and use the internet and social media as their primary voice outlet – including on political matters. Their understanding of the digitized world represent a huge untapped resource in politics today. Mind you, young people in the region tend to pick integrity over corruption and are critical to how corruption has impacted on development.

The bumpy road ahead

Democratic development is challenging. It does not represent a linear path but instead a bumpy road with ups and downs – progress is followed by stagnation and regression before yet again gaining speed. In Asia we see tremendous variation – within the region, within sub-regions and even within countries. Democracy’s resilience is being tested daily, in Asia as across the world.

This November, International IDEA is launching its first Global State of Democracy report, which looks more closely into the resilience of democracy. Alongside the report is a set of Global State of Democracies, which highlights how democracy fared from the 70s to the present. The trends in the upcoming report reaffirm the ups and downs, but underscores democracy’s resilience.

Democracy cannot be taken for granted, and further measures to safeguard democracy through innovative, flexible and adaptive approaches are urgently required of policymakers and citizens alike.

Leena Rikkila Tamang is the Regional Director for International IDEA’s Asia & Pacific Programme. Mette Bakken is Acting Programme Manager for International IDEA’s Nepal Office.