North Korea frequently mentions needing nuclear weapons to prevent an American invasion and scholars contend that North Korea cannot trust assurances by the United States that it would not try to remove the regime even if it relinquished these weapons. Kim Jong-un’s frequent provocations led U.S. President Donald Trump to respond in August that North Korean threats could be met with “fire and fury like the world has never seen,” which North Korea responded to with threats to launch strikes around Guam. Though that never occurred, continued discussion of military options has not stopped and analysts worry that Kim may use Trump’s visit to South Korea as a pretext to test another long-range missile. Meanwhile, the Pentagon claims that any military action to remove North Korea’s nuclear arsenal will require a significant commitment in ground troops. This raises the likelihood of a high number of American casualties, although it’s difficult to estimate without assumptions of American commitments of additional forces in the region.

Despite the attention to North Korea’s recent threats of war, few surveys ask the American public about North Korea, much less multiple questions about the country. I surveyed 1,035 Americans about North Korea online through mTurk Amazon in late October. Scholars frequently use mTurk for experimental designs where respondents are randomly assigned slightly different versions of questions to identify the extent to which framing and priming influence perceptions. While often lacking the demographic representativeness of the American population as a whole, mTurk provides a broader cross-section of society than social science experiments of college students in a university lab.

Typical caveats aside, the results suggest important distinctions in how groups of Americans view North Korea. Across the board, however, Americans’ support for military conflict with North Korea is particularly sensitive to Korean casualties.

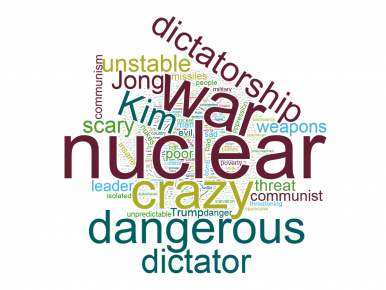

In the survey, I first asked people for the first three words or phrases that come to mind when thinking of North Korea. The most common words are largely predictable (see the word cloud). For example, “nuclear” (and variations like “nukes”) appeared the most, mentioned 200 times and by 27.9 percent of respondents, with references to “danger” or “threat” (159 times), “war” (153 times), and references to the regime as a dictatorship (148 times) each mentioned by at least 20 percent of respondents. However, several statistically significant patterns were unexpected. Trump was not mentioned often (3.9 percent of people, compared to 10.6 percent that mentioned Kim Jong-un), and was more likely to be mentioned by women, Democrats, and those who did not go to college. In general Democrats were more likely to mention Trump, Kim, authoritarianism, and North Korea as “poor” while Republicans comparatively emphasized “evil,” “danger,” “crazy,” and “communist.” In addition, upper income respondents (over $100,000/year) were more likely to mention nuclear weapons and to use terms like “crazy,” “insane,” or irrational” than other income brackets.

In the survey, I first asked people for the first three words or phrases that come to mind when thinking of North Korea. The most common words are largely predictable (see the word cloud). For example, “nuclear” (and variations like “nukes”) appeared the most, mentioned 200 times and by 27.9 percent of respondents, with references to “danger” or “threat” (159 times), “war” (153 times), and references to the regime as a dictatorship (148 times) each mentioned by at least 20 percent of respondents. However, several statistically significant patterns were unexpected. Trump was not mentioned often (3.9 percent of people, compared to 10.6 percent that mentioned Kim Jong-un), and was more likely to be mentioned by women, Democrats, and those who did not go to college. In general Democrats were more likely to mention Trump, Kim, authoritarianism, and North Korea as “poor” while Republicans comparatively emphasized “evil,” “danger,” “crazy,” and “communist.” In addition, upper income respondents (over $100,000/year) were more likely to mention nuclear weapons and to use terms like “crazy,” “insane,” or irrational” than other income brackets.

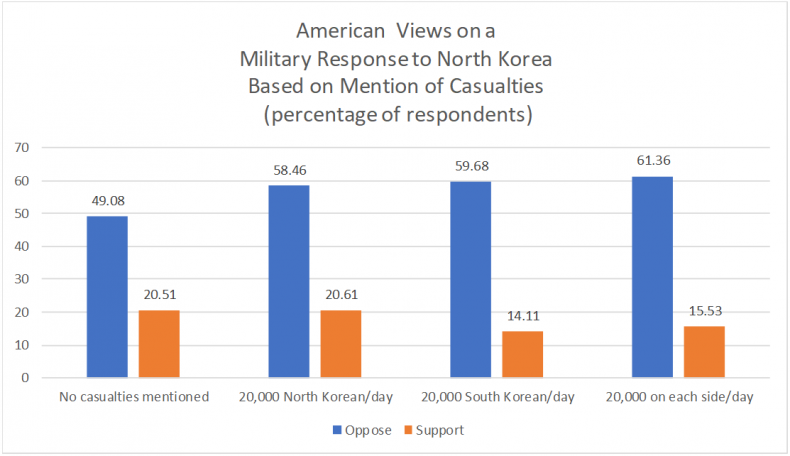

Next in the survey I asked whether respondents would oppose or support an American military response to North Korea. However, through randomization, some people were also provided additional information. Some were told that in the initial stages of military conflict, North Korean casualties could be as high as 20,000 a day. Others were told that South Korean casualties could be as high as 20,000 a day. The last group was told that both sides of the DMZ could see casualties of 20,000 a day. These numbers, in line with estimates elsewhere (see here, here, here, and here), assume only the use of conventional weapons. A Congressional Research Service report estimated that as many as 25 million Koreans on both sides and as many as 100,000 American citizens could be affected by military escalation.

Regardless of the information received, Americans generally opposed a military response. However, the mention of potential casualties on either side of the Korean peninsula increased opposition. In general, Democrats were more opposed to a military response and Republicans more supportive, but the same pattern of increased opposition when casualties are mentioned at all is seen in both groups. Research in social psychology on prospect theory shows that people respond differently to otherwise similar conditions when framed as a potential loss versus a gain. However, the results here suggest perhaps a more general loss aversion even in the absence of estimates of American casualties. The simple mentioning of casualties at all appears to trigger respondents to start thinking about American lives potentially lost.

Furthermore, although previous research finds Americans supportive of additional troops if North Korea attacks South Korea, respondents in my survey that received any of the casualty-referencing prompts were less supportive of increasing the number of U.S. armed forces stationed in South Korea (currently at approximately 28,000 soldiers). In addition, respondents that received information on potential South Korean casualties were more likely to say North Korea did not have a right to nuclear weapons.

Overall, the results not only reaffirm the divisions in perceptions among the American public, but suggests that most have not considered the potential costs of conflict.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. His research focuses on the domestic and international politics of Taiwan, Japan, and the Koreas.