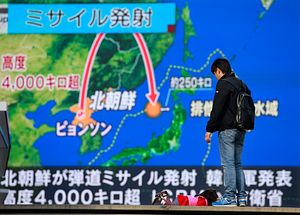

A public statement issued by the North Korean government on yesterday’s test launch of a new intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), called the Hwasong-15, possibly contains language intended to signal that the Kim Jong-un regime is willing to engage in diplomacy in the near future.

While the November 29 statement emphasizes that the new missile model is purportedly tipped with “a super-large heavy warhead” capable of “striking the whole mainland of the U.S.” and that the test succeeded despite “vicious challenges” by the “U.S. imperialists,” it also stressed Pyongyang’s commitment to maintain world peace and more importantly announced that it may finally possess a credible nuclear deterrent capability.

“As a responsible nuclear power and a peace-loving state, the DPRK [Democratic People’s Republic of Korea] will make every possible effort to serve the noble purpose of defending peace and stability of the world,” the statement reads. As North Korea watchers know, Pyongyang has consistently been claiming that its nuclear missile program contributes to peace and stability in the world.

The statement becomes more interesting and unique when it notes that the DPRK has “realized the great historic cause of completing the state nuclear force” and that the new Hwasong-15 ICBM meets “the goal of the completion of the rocket weaponry system development set by the DPRK.” It also stresses that the country’s missiles“will not pose a threat to any country” and will only be used to defend against “U.S. imperialists’ nuclear blackmail policy and nuclear threat.”

The statement by the DPRK that it has accomplished its goal of fielding a credible nuclear deterrent to prevent U.S. military action is a first and deserves attention, whether true or not. For one thing, it could be interpreted as a deliberate signal to underline Pyongyang’s willingness to engage in dialogue with Washington in the not so distant future. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the statement does not contain any references to future tests.

It is important to note that this interpretation presumes that North Korea is indeed interested in some form of direct exchange with the United Stares. The ostensible de-escalatory language in the statement could also just be a tactical move by North Korea to influence and divide public opinion in the U.S. by deliberately juxtaposing (ostensibly toned down) North Korean rhetoric and the bellicose words of U.S. President Donald Trump who has repeatedly threatened preventive war.

Either options are a possibility, yet we should not expect major policy shifts in the coming weeks. Furthermore, yesterday’s announcement in no way means that North Korea will stop its nuclear or missile tests. For one thing, it appears that the DPRK has still not mastered reentry technology, although U.S. government sources have claimed that North Korean reentry vehicles could likely hit targets in the continental United States if fired at a minimum energy trajectory.

There is still the possibility that the DPRK will conduct an atmospheric nuclear test over the Pacific Ocean. Indeed, it is more than likely that North Korea will continue its tests in order to be able to offer up a possible testing freeze as a bargaining chip in future negotiations in exchange for a lifting of sanctions. Importantly, any new tests will also increase the chance of a military confrontation.

Still, talks remain a real possibility.

An October statement by a North Korean official quoted by CNN appears to confirm that the North might be more inclined to talks following the recent missile test. “Before we can engage in diplomacy with the Trump administration, we want to send a clear message that the DPRK has a reliable defensive and offensive capability to counter any aggression from the United States,” the official said.

The same official told CNN this week that a reliable defensive and offensive capability would not just entail the successful “testing of a long-range ICBM” but also an above-ground nuclear test, which is strictly prohibited under the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. Such a test would be seen as a massive escalatory step by the United States and its East Asian allies and could trigger a military response.

Yet it does not necessarily have to come to that. As long as the North thinks that it has persuaded the United States that it can successfully fire nuclear missiles at U.S. continental targets, Pyongyang might abstain from an above-ground test. Indeed, U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis’ remarks yesterday may have been deliberately chosen to acknowledge North Korea’s credible deterrent capability when he said that the missile launch demonstrated the North’s ability to hit “everywhere in the world.”

However, there are little signs that the Trump White House has shifted the prevalent U.S. strategy of trying to deter, isolate, and sanction North Korea while refusing any sort of direct dialogue.

Nonetheless, the United States has privately conveyed to North Korea that it is willing to commence talks without pre-conditions. Conversely, while North Korea has publicly been insisting on the U.S. to drop its hostile policy against the regime and to begin treating the DPRK as a nuclear power as pre-conditions to talks, it has in private also repeatedly expressed its willingness to start a dialogue.

But this is likely to go nowhere until Pyongyang feels it has achieved its major strategic goal of obtaining a nuclear first strike capability. The November 29 statement might indicate that this endpoint is coming into sight rather sooner than later. Indeed, a first test for both countries’ willingness to at least be open to talks could come as early as January should Kim Jong-Un announce the completion of the regime’s nuclear weapons program during his annual new year’s address.

The United States has learned to live with another nuclear power that used to be considered a rogue state and threat to world peace in the past (See: “How a State Department Study Prevented Nuclear War With China”). The U.S. will also have to learn to learn how to live with another nuclear armed rogue state unless it wants to risk a war involving the use of weapons of mass destruction.