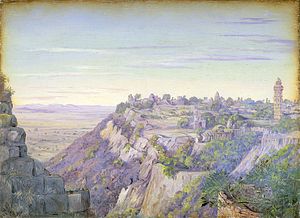

The only queen that ruled over the great fort of Chittorgarh when I visited it in 2004 was named Ambience. The castle, a condominium of stone and nature, is vast and tranquil, with spaces for long, peaceful walks between the monuments. Although it was silent, history was whispering from every tower, window and corner. Located in the southeast corner of Rajasthan, India’s largest state in terms of territory, Chittorgarh is a great place to visit for history-lovers. Strolling around it, you can imagine how large a population could shelter within its walls and how difficult it was for invaders to overpower it, with the sturdy fort sitting atop a rocky hill. And yet it was conquered.

A Calm Before a Siege

In 1303, the army of the Turkish Muslim sultan, Alauddin Khalji, set off from the ruler’s seat in Delhi to defeat King Ratan Singh, the ruler of Chittorgarh, a Hindu by religion and a member of the Rajput community.

“The fort was formidable, the terrain mountainous. The Rajpūts fought valiantly, but finally the ruler, Raja Ratan Singh, submitted. The Sultan entered the fort at the end of August 1303. The Raja’s family were not persecuted, but the village headmen were slaughtered,” writes S.A.A. Rizvi in the authoritative The Wonder that was India, vol II.

That was 600 years ago and it was not the last time that the keep fell.

In 2017, the castle has faced a new siege (of sorts). The queen called Ambience is not ruling over Chittorgarh at the moment, her place has been taken by the angry princess named Controversy. At certain times this year, a group of protesters have blocked the fort’s entrance or organized protests next to its walls. These ongoing demonstrations are, in a way, connected to the story of the 1303 siege. Yet, throughout this ongoing controversy history has remained silent and hidden behind the ramparts. While its voice was defended in much of the media and academia, on the streets fiction collided with fiction.

The protests began because of an upcoming Bollywood film, Padmavati. Sanjay Leela Bhansali, the director of the work, known for his taste for history and historical fiction as movie material, as well as for specializing in grandiose design and colorful backgrounds, chose the story of Chittorgarh’s siege as the setting for his movie. Expect a clash of kings and a love story, served with vast spaces, large historical buildings (or their look-alikes), and a host of people fighting iron to iron and dancing in flashy attire. The film is supposed to tell the story of Sultan Khalji’s attack on Chittorgarh but it also focuses on the character of Queen Padmavati, the wife of king Ratan Singh, though the existence of such queen does not seem to be confirmed in any historical source.

Bhansali was clear that the movie is a work of fiction so there is no reason to judge it with the harsh facts-and-sources measuring rod of historians. Queen Padmavati appears in certain poems, the earliest known being Padmavat by Malik Muhammad Jayasi, written possibly around 1540, and thus more than 200 older than Khalji’s siege itself.

Jayasi told the story of Padmavati, the queen from the “Singhala kingdom” (which would be modern Sri Lanka), who became the wife of King Ratan Singh. Historically speaking it would seem that the main reason for Sultan Khalji’s attack on Chittorgarh was his quest for dominance, as at the time Chittorgarh was situated on a trading route towards central India and further on to south India, regions which the Turkish sultan had been mercilessly plundering. In the poet’s version, however, Alauddin Khalji stormed Chittorgarh’s fortress because he wanted to capture Padmavati, famed for her astounding beauty. Moreover, while Rizvi, quoted above, wrote that the sultan spared the king’s family, in Padmavat all men died while defending the castle and all the women committed suicide on a funeral pyre, preferring to immolate themselves rather than fall prey to the invaders. Eventually Khalji conquered an empty fortress, a kingdom of ash. Thus, the poet showed us what desire can do to peoples’ lives.

Through Jayasi’s work and later poems, the character of Padmavati and the dramatic end of her life became popular across northern India and became one of those stories that are difficult to counter, as among some people they may be better known than the actual history. Hence, there are many people for whom Padmavati is a true historical persona.

A Review Before a Movie

Although we do not know yet how much of Padmavat there will be in Padmavati, it seems safe to assume that one of the poem’s main plot points – the sultan’s attack on the fort being caused by his wish to kidnap the queen – will be included in the movie. This would have seemed to be the perfect ammunition for radical Hindu political goals. We have a cruel Muslim ruler dreaming of capturing the Hindu queen and slaughtering the many Hindus standing in his way. The Hindu radicals should rather distribute free tickets for the premiere and write ecstatic reviews on how the movie captures the essence of past Hindu-Muslim relations. Moreover, while nobody revealed the spoilers from the grand finale, it seems nearly certain that if he has Padmavati in the movie, we should also witness her death in flames in the end of the story (or will we?). In that case, the Hindu extremists would have another reason to uphold the movie as history: a Hindu queen chose death over royal imprisonment at court of Muslim ruler.

But what happened was the reverse. A block of radicals were agitated about a rumor that the movie will include an erotic scene between Padmavati and Alauddin Khalji. And so it happens that the actor playing the villain, Ranveer Singh, is the new hot male star of Bollywood while the role of Padmavati will be played be Deepika Padukone, one of India’s most popular actresses. The Western viewers might have seen her in XXX: Return of Xander Cage but she has accomplished much more in Bollywood. Some Hindu nationalists cried that such a love scene as was rumored to be in Padmavati would be “distortion” of history, as if the movie was history and as if Padmavati herself was historical. Possibly they were also perturbed at the very thought of a Hindu queen indulging in carnal pleasures with a Muslim invader. Under fire from fringe and dangerous groups, the creators of the movie promised that no such scene will be included in Padmavati.

But that did not placate the extremists. The main protesting groups were seemingly small and otherwise little-known: the Rajput Karni Sena, the Kshatriya Samaj, the Akhil Bharatiya Kshatriya Mahasabha. The Rajput Karni Sena claims to represent the Rajputs, an ethnic community to whom the king of Chittorgarh had belonged. Padmavati, the organization claimed, is a movie that hurts the “sentiments” of the “whole community” of Rajputs. The agitated members of the Rajput Karni Sena first attacked the sets of the movie while it was being shot. As the film’s premiere, originally scheduled for December 1, approached, Rajput Karni Sena demanded a complete ban on Padmavati, blocked the entrance to the Chittorgarh fort and staged a sit-in protest; in November tourists were not able to enter.

The protests and criticism rose to overblown proportions, eventually becoming stronger than the promotional activities around the film, and crossing the borders of law and civilization. A cinema hall was attacked in the town of Kota, not far from Chittorgarh. At some places the demonstrators burned the effigies of actress and the director. A member of the Kshatriya Samaj has put a 50 million rupees bounty on the heads of Deepika Padukone and Sanjay Leela Bhansali. The amount of the “reward” was doubled by Suraj Pal Amu, a member of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and until recently a member of the government of the state of Haryana. Moreover, a member of the Akhil Bharatiya Kshatriya Mahasabha raised the stakes by offering 10 million rupees to a person who would burn the actress. Fortunately, none of that has happened. The most gloomy incident so far was the finding of the body of a low-caste man in Jaipur, he’d been hung. A barely readable sentence scribbled on a nearby stone said: “We do not only hang effigies, Padmavati.” In this case, however, we know so little of the incident that it would be preposterous to assume it was only connected to the movie controversy. At any rate, one wonders if the radicals feel the irony of the symbolic role change: now they are laying a siege of sorts to the fortress (like Khalji once had) and threatening the life of the actress who is playing the role of the queen.

The mainstream Hindu nationalists did not fully lend their support to these fringe group: some distanced themselves from the issue, most chose to remain silent and some voiced similar concerns about the movie, although couched in a tone that was not so bellicose and threatening. The movie was cleared by the censors’ board and a few journalists considered closer the government than to the opposition were allowed to watch Padmavati and found nothing objectionable in it. The controversial Arnab Goswami, for instance, insisted that the queen was historical but considered this the reason for the movie’s greatness. “So if Rani Padmavati were to be a myth, she shall now be a greater myth and if she is a part of our history, which she is, then she shall be entrenched even deeper” he said. “In our history, this Karni Sena will be left looking utterly foolish once this film hits the box office because far from an intimate moment, Alauddin and Padmavati — Ranveer and Deepika — don’t even share one single frame together in the film.”

Yet, in face of the protests, the premiere was delayed (so if you happen to live in London you can see Padmavati earlier than the inhabitants of India). Moreover, the governments of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh (where the BJP happens to be in power) banned the movie, as did the government of Bihar (where BJP is a coalition partner). What is more troubling is that even some members of other political camps, such as the Chief Minister of Punjab (who belongs to the Indian National Congress, BJP’s main rival) expressed similar reservations about Padmavati. This brings us to the real sultans of the story: the politicians, who are the sultans of the swing in sentiments.

A Marketing Campaign Before the Elections

This is not the first time that a movie in India has been attacked by protesting groups which seem to appear out of nowhere. Various films have been under fire for the alleged hurting of sentiments of particular religious communities, ethnic groups or even specific castes. Sometimes the accusation is true but quite often they are off-the-mark or downright absurd. Even a single word may be found objectionable, leading to court cases or street protests. Possibly the most insane charge was levied on one of Bhansali’s earlier movies when the criticizing person found it condemnable that the name of the god Ram appeared in the movie’s title. For people of this sort, wrestling with the movie’s makers may be an attempt to squeeze some money from a powerful film company, either through a court case or a sheer threat of one. And for radical outfits the popular movies are like marketing balloons, to which they cling, flying to the heights of undeserved and short-lived fame. If not for the Padmavati controversy, only a few in India would ever have heard about the Karni Rajput Sena.

Some aspects show that the controversy is fabricated. In the fortress of Chittorgarh, the protesting Rajput Karni Sena members forced the Archaeological Survey of India to cover an information plaque that called the story of Padmavati a “legend.” Moreover, the same fort saw the removal of the mirrors through which – it was wrongly claimed – Alauddin Khalji once had a glimpse of Padmavati. Both the plaque and the mirrors stood in the castle for years, and somehow did not invite the ire of the extremists.

Their criticism is also highly selective. The Hindu nationalists have a tendency to perceive Indian society through the lens of the Hindu-Muslim divide, and yet somehow ignored the fact that Muhammad Jayasi, the author of Padmavat, was a Muslim. Moreover, if his poem is to be believed, Padmavati was of Singhala origin and hence not a Rajput by birth. In that case, why would the Rajput community be so outraged? This is unless we take a patriarchal view of the matter (which the protesters possibly do): Padmavati became a Rajput on the account of her marrying a Rajput king. And should we really consider the historicity of the poem whose characters include a talking parrot, and god of the Ocean and his daughter?

It may be assumed that the real battle is not being fought in the fort and not on the streets, not in the books of poets or academics, and not even in the media or in the courts. The real battle is in politics. The governments of the states that banned the movie or expressed reservations about it are mostly those that must consider the feelings of the Rajput community living in their states. Perhaps more importantly the state of Gujarat (the Indian Prime Minister’s home turf) is going to the polls in December, during which month the movie was supposed to hit the screens. In Gujarat, not only the ruling BJP spoke against releasing the movie but the main opposition party (the Indian National Congress) joined the camp.

It is ironic to hear Hindu radicals stating that they are defending history against distortions. Firstly, they are claiming the existence of a scene in a movie which they have not seen and the makers of which point out does not even exist. Secondly, the movie itself is a work of fiction. And thirdly, the alleged scene involves a fictional person that possibly first appeared in a poem which itself is a work of fiction. Thus, the entire controversy is a false accusation of a fictional work which is at least partially based on another fictional work. It’s not just distortion – it’s a distortion within a distortion within a distortion.

At the end of the poem Padmavat, the sultan enters the conquered yet empty fort and realized that this was not what he wished for.

After the Padmavati controversy, the politicians and their affiliates will probably win the electoral battle but they will not pause to look at the ashes of history they leave in the wake of their siege.

The movie itself is bound to become popular. Once it does, it will become yet another brick out of which queen Padmavati’s popular image and fame will be built. More than ever before, it will be difficult to ever point out that Padmavati’s historicity has not been proven.