On February 25, 1956, in a closed session of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev gave his “Secret Speech” denouncing Stalin and his cult of personality. The political tremors from this questioning of Communist doctrine traveled across the border to Beijing where Chinese-leader Mao Zedong initially responded with an invitation for criticism (“Let a thousand flowers bloom”), only to double down on his relentless pursuit of internal enemies and continuous revolution. In search of a strategic breakthrough, Mao embarked on the Great Leap Forward, a sweeping, terrifying and, ultimately, catastrophic economic program designed to surpass the achievements of Western industrialization in an accelerated timeframe (in one “big bang”).

Beginning with Deng Xiaoping in 1978, China has since charted a different course, one of economic reform and modernization. This internal change dovetailed with external factors such as the end of the Cold War and expansion of globalization. Nearly forty years later, with hundreds of millions of Chinese lifted from poverty, a growing middle class, and the world’s second largest economy, Beijing’s ascent is one of the most important narratives in modern history. China’s rise has also been graded and moderated in comparison to the turbulent and tragic character of Mao’s era.

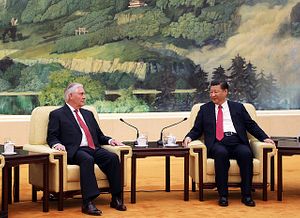

However, we are seeing Beijing turn way from the steady “hide and abide” approach of the Deng period. Buoyed by its economic performance following the global financial crisis and with President Xi Jinping’s recent consolidation of power, China may be entering a new daring revisionist phase, this time on the global stage. On October 18, 2017, at the 19th Party Congress, standing in the majesty of the Great Hall, Xi proclaimed that he would be leading China into a “new era.”

Period of Strategic Opportunity

According to the 2017 annual report of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC), China’s senior leadership believes we are amidst a “period of strategic opportunity” during which China can expand national power and achieve objectives such as unification with Taiwan and control of disputed territory along China’s periphery. The USCC is a non-partisan Congressional body mandated with investigating the national security implications of U.S.-China relations, including Chinese military plans, strategy and doctrine.

Three USCC commissioners, including former Senator Jim Talent, offered in an addendum to the report intended to sound the alarm for U.S. policymakers: “In short, China is not just an asymmetric threat to the United States, or even a near-peer competitor. It has become, in its region, the dominant military power. That fact, more than any other, explains why China’s aggressions over the last five years have been successful.” These actions include “the ‘great wall of sand’ in the South China Sea, the ADIZ in the East China Sea, aggression against the Philippines in defiance of international law, coercion of Vietnam over the Spratly Islands, increasing pressure on Taiwan, harassment of Japan over the Senkaku Islands, and other provocative acts.” We could add to this list the stand-off with India in the Doklam region of the disputed China-Bhutan border.

Beyond contested borderlands, Beijing has also begun to flex its muscles on the world stage. On August 1, 2017, China opened its first permanent overseas military base in Djibouti, strategically located near the Gulf of Aden, adjacent to the Arabian Sea – and also a short drone flight away from Camp Lemonnier, a major U.S. counterterrorism hub and America’s only permanent military base in Africa. In May, Xi led a forum featuring China’s “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) scheme of interconnected multimodal corridors linking China with Asia, Africa, and Europe, and encompassing approximately 60 countries. Xi pledged an additional $124 billion for OBOR’s large-scale infrastructure projects, which involve financing by the Beijing-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), as well as from the Export-Import Bank of China and China Development Bank.

In 2017, China also engaged in significant international institution-building activities such as expansion of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to include the major (and dueling) powers of South Asia, India and Pakistan, and continuation of BRICS, hosting the 9th annual summit attended by the leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. While the U.S. was withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Beijing continued negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade agreement involving 16 countries in the Asia-Pacific that account for half of the world’s population and almost one-third of global GDP.

Military Modernization and Advanced Weaponry

Underlying China’s new posture is the country’s military modernization program. Beijing continues to improve its military software – its command-and-control structure. Over the last two years Beijing has centralized and consolidated space, cyber, electronic warfare, signals, and potentially human intelligence capabilities under the “Strategic Support Force” within the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). According the USCC report, this could enhance the Chinese military’s ability to conduct integrated joint operations by providing a wide range of collection capabilities including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support. Responsibility for the intelligence and reconnaissance functions involved in locating and tracking targets will be centralized at the Strategic Support Force rather than dispersed among different units. In the event of a conflict, the USCC warns that Washington must assume this advancement will contribute to Beijing’s anti-access/anti-denial (A2/AD) capabilities vis-à-vis U.S. forward deployments in the region.

Additionally, China continues to invest in military hardware supported by a growing military budget, announced to be $151.1 billion for 2017 (a likely underestimation, but 7 percent greater than the previous year), and still well below the $611 billion in U.S. in defense spending for 2016, as reported by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. But the military budget is only one consideration. The development of advanced weapons reflects a broader sophistication in the fields of science and technology, inclusive of private sector innovation. In turn, the USCC highlights China’s “comprehensive and state-directed approach” to leverage government funding, commercial technological exchange, foreign investment and acquisitions, and talent recruitment to bolster its dual-use technological advances.

Of particular consequence is Beijing’s prioritization of “leap-ahead” technologies that can provide a “surprise breakthrough” that changes the strategic balance in the Asia-Pacific and beyond. More specifically, the USCC cites six examples: (1) maneuverable reentry vehicles, (2) hypersonic weapons, (3) directed energy weapons, (4) electromagnetic railguns, (5) unmanned and artificial intelligence (AI)-equipped weapons, and (6) counter-space weapons. According to the USCC, China is employing the strategy of shashoujian, which translates as “assassin’s mace weapon,” in which a weaker power utilizes a specific capability to defeat a stronger one. To borrow from the pioneering game theorist, Thomas Schelling, China seeks a “strategic move” that induces the United States into making a choice constrained by the debilitating threat of advanced weaponry.

For example, the USCC reports that China has developed unmanned aerial and underwater vehicles, and conducted research on unmanned ground and surface vehicles with the potential for autonomous swarm control capabilities. For example, at the Guangzhou Airshow in February 2017, China demonstrated a record-breaking formation of 1,000 rotary-wing drones based on pre-programmed routes. According to the USCC, such swarming techniques could be used to create a distributed armed system which, coupled with AI capabilities, could be used for saturating and overwhelming the defenses of high-value weapons platforms such as aircraft carriers. This could impact the outcome of a potential U.S.-Chinese engagement in the South or East China Sea.

For counter-space technology, the USCC documents Beijing’s small-satellite “rendezvous and proximity operations” that could be applied against U.S. commercial or military satellites. China can use space-based platforms to launch kinetic, non-kinetic physical, or electromagnetic attacks. Combatting and deterring the “space superiority” of the United States is critical for a potential conflict, for example, in the Taiwan Strait involving long-range precision strikes. This is consistent with an earlier finding of the USCC that Beijing has rejected international efforts, such as the EU-proposed International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities, which may curtail its counter-space weapons like co-orbital anti-satellite systems. As I noted in these pages, with space increasingly becoming an area of international competition, from economic to strategic, we should expect China and other powers to militarize their space technology, even under the guise of civilian or commercial use.

The USCC concludes with a blunt warning: “The United States for the first time faces a peer technological competitor – a country that is also one of its largest trading partners and that trades extensively with other high-tech powers – in an era in which private sector research and development with dual-use implications increasingly outpaces and contributes to military developments.” In an international environment involving multi-dimensional spheres of warfare (land, sea, air, space, and cyber), today’s race to develop frontier technology could determine tomorrow’s balance of power.

National Greatness and Elusive Equilibrium

The international security dynamic remains tense and unpredictable. With their separate but comparable appeals to nationalism, both China and the United States have added to this uncertainty. Xi, who has become the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao, has vowed to realize a new “Chinese Dream” – the great restoration of Chinese power and “lost” territory – galvanizing crowds at Communist Party rallies. Propagandists have reportedly carried “with Mao-like zeal” the revised Communist Party charter enshrining “Xi Jinping Thought” to outposts in the South China Sea.

However, standing in the way of Xi’s Chinese renaissance is a security architecture buttressed by American power. For his part, U.S. President Donald Trump has built upon the populist wave he fostered in the 2016 election by calling for a renewed American sovereignty and patriotism, supported by a substantial increase in defense spending. He has also threatened war on China’s doorstep, the Korean peninsula, and Chinese trade practices, from aluminum steel imports to intellectual property protections. Unsurprisingly, given the unfinished and uneven development of Trump’s “America first” foreign policy, the White House continues to struggle in finding balance in the U.S.-China relationship.

Indeed, equilibrium will remain elusive when there are competing visions of national greatness. As Henry Kissinger once observed, “No power will submit to a settlement however well balanced and however ‘secure’, which seems totally to deny its vision of itself.” Political Scientist Robert Gilpin adds that a state will “never cease” in pressing what it regards as its “just claims on the international system.”

For China and Xi, this may mean pressing to resolve outstanding territorial claims and continuing to make a new regional order reflective of China’s self-image. For the United States and Trump, this may lead to readjustment of the bargain underlying U.S. trade and a reassertion of American hard power in the “Indo-Pacific” – including, if necessary, engaging in preemptive self-defense against North Korea. It does not take Thucydides to recognize that, within this unsettled context, a Chinese leap forward, through military modernization and advanced technology, will lead to a new and dangerous phase in international relations.

Roncevert Ganan Almond is a partner at The Wicks Group, based in Washington, D.C. He has advised the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission on issues concerning international law and written extensively on maritime disputes in the Asia-Pacific. The views expressed here are strictly his own.