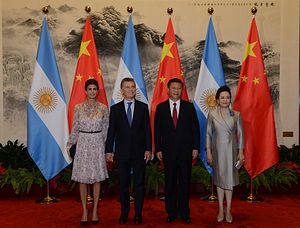

In May 2017, Chinese president Xi Jinping welcomed Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri in Beijing by proclaiming that “Latin America is the natural extension of the 21st century Maritime Silk Road” while applauding Argentina’s support and participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Sino-Argentine meeting underscored the fact that, four years after it was revealed, the BRI is rapidly being expanded to Latin America and paying dividends for China and its partners. It is also evident that the United States appears content to withdraw from the region and cede leadership to China, a startling state of affairs considering that Latin America had long been considered to be part of the U.S. geostrategic backyard.

While Latin America used to be considered the United States’ geostrategic backyard, covered by the Monroe Doctrine, Washington has been neglecting and withdrawing from the region for a long while now. Twenty years ago, in 1997, U.S. Southern Command moved from Panama to Miami with revised priorities, objectives, and capabilities. In 2000, Panama officially took over the Panama Canal from the United States. In the aftermath, the canal lost some of its strategic importance to Washington, but its importance to the rest of the world did not diminish. As China’s economy burgeoned, it also sparked a wave of eastbound exports from Brazil to China, prompting Beijing to seriously court various Latin American governments.

Then in 2013, with the writing on the wall and Washington unable to block Chinese initiatives, then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry effectively announced the end of American regional leadership in Latin America by declaring that “the era of the Monroe Doctrine is over.”

With this context in mind, it’s not clear whether the U.S. government received any prior notice before Panama officially recognized the People’s Republic of China over the Republic of China (Taiwan) in June 2017, an unthinkable scenario just a few short decades ago.

Panama is the most recent example of a Latin American country pivoting toward China at the expense of the United States. Just five months after China and Panama established official diplomatic relations, Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela Rodriguez visited Beijing in November 2017. During the visit, Varela inaugurated Panama’s embassy in Beijing and consulate office in Shanghai, as well as adopting 19 agreements and a joint declaration with his Chinese counterpart. Perhaps the most important agreement is the inclusion of Panama in the BRI. Going forward, Panama will likely play a key part in China’s efforts in Latin America, with the Panama Canal and the country’s strong financial and logistics platforms giving China key infrastructure capabilities in the region.

The future of U.S.-Panama relations is increasingly unclear. With Panama looking to China for support and leadership, Washington may in fact consider it a potential problem. Given that the Trump administration wasted no time in taking a confrontational tone toward Beijing, Washington may be putting China’s partners on notice.

Thus far, the Trump administration strongly prefers a policy of withdrawal and retrenchment rather than engagement, prompting Richard Haass, the president of the Council on Foreign Relations, to describe Trump’s foreign policy as “the Withdrawal Doctrine.” While there is a legitimate debate over whether the United States overplayed its hand after the unipolar moment following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Washington is now in danger of damaging its core interests through neglect.

Consider, for instance, the Trump administration’s reluctance to provide global public goods. Certainly, internal financial woes and external overstretch have made it increasingly untenable for the United States to provide global public goods. But while past presidents, from Jimmy Carter to Barack Obama, have lamented this state of affairs, Trump is the first to truly force the issue, declaring that the United States “does too much for the world.” Practically, what this means is that the United States is disengaging from crucial international forums and decision-making bodies.

For example, on October 12, the U.S. government announced that it would leave the United Nations Educational, Cultural, and Scientific Organization (UNESCO), an organization that Washington helped found after World War II. Perhaps worse still, the Trump administration is threatening to pull out of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Pulling out of the WTO would be a seismic change in policy and has predictably triggered backlash from fellow WTO members. As ministers from the 164-member body gathered for the 11th WTO Ministerial Conference on December 10 in Buenos Aires, Latin American leaders issued a clarion call to strengthen the multilateral trading system.

For Latin American governments, Trump’s policies, rhetoric condemning immigrants, and calls to build a border wall, read like an abdication of leadership. When Trump does not even appear interested in appointing an assistant secretary of state for western hemisphere affairs to be confirmed by Congress, it is difficult to take Washington’s commitment to the region very seriously.

It is hard to imagine a more stark contrast from Trump’s withdrawal doctrine than China’s call to embrace globalization. Beijing has championed the ambitious BRI, which proposes to connect China with markets in Asia, Europe, and Africa through infrastructure development. During the inaugural ceremony of the Belt and Road Forum in May 2017, Xi Jinping portrayed the BRI as “economic globalization that is open, inclusive, balanced and beneficial to all.” China also invited the World Bank and other international institutions to join it in meeting the needs of developing and developed countries.

Whether the BRI meets all of Beijing’s expectations in Latin America remains to be seen. But even now, it contributes to the future of Sino-Latin American relations in three ways. First, China is forging new markets and exporting Beijing’s model of state-led expansion. Second, China is building infrastructure as a diplomatic tool and expanding its circle of friends by inviting more South American countries to join the Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank. Third, China is extending the BRI to the Americas and helping enhance the region’s connectivity to the rest of the world through projects such as the proposed 19,000-kilometer, trans-Pacific fiber-optic internet cable from China to Chile.

With so little opposition from the United States, China’s Belt and Road Initiative will naturally and easily extend to Latin America. This may be acceptable to the current American administration. But American influence in Latin America, once lost to China, will be extremely difficult to recover.

Antonio C. Hsiang is Professor and Director of the Center for Latin American Economy and Trade Studies at Chihlee University of Technology, Taiwan.