Human rights activists in Indonesia have gained a brief respite after the Constitutional Court on December 14 narrowly rejected a petition to alter the criminal code to make extra-marital and homosexual sex illegal. The petition for the judicial review was lodged by a conservative group called the Family Love Alliance (AILA) and was aimed at changing the substance of a number of articles in the criminal code to reflect, as this group contended, religious values and social norms that prevail in Indonesia. Specifically, AILA requested amendments to articles 284 and 292 of the criminal code to render all extra-marital sex and homosexual sex illegal.

The judicial review attracted national and international attention and was one of the longest in the history of the Constitutional Court. The trial caused divisions between social groups and in the panel of judges presiding over the case. This division was reflected in four of the nine judges, including the chief justice and deputy chief justice, putting forth a dissenting opinion that stated that the criminal code should be brought into line to reflect the living law that prevails in Indonesia by outlawing all forms of extra-marital and homosexual sex and thus the petition should have been granted.

The dissenting opinion stated that homosexuality constitutes a behavior that is intrinsically abhorrent according to religious law and community values in Indonesia and that the original formulation of the criminal code was a victory for homosexuals. The dissenting judges contended that the narrow formulation of the article in regulating only adultery and not fornication was influenced by European secular-hedonistic philosophies that differ from the sociological condition of Indonesian society.

Currently, only adultery is illegal under Indonesian national law; other consensual sexual relations between adults are not regulated by law. The parties who supported the petition for the judicial review put forward arguments that the law as it currently stands does not reflect the religious values or morals that exist in Indonesian society. These groups, including the Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI) and Association of Islamic Wives (Persistri), argued that the criminal code, which was drafted in colonial times, is a product of Western liberalism and reflects a tolerance to homosexuality and extra-marital sex that is not applicable to the living law in Indonesia.

Related parties to the judicial review who opposed the petition explained to the court that if the petition was approved by the court, widespread criminalization of large cross-sections of Indonesian society would occur. If the criminal code was to be altered in accordance with the petition, unmarried youths, LGBT groups, couples whose marriages are not registered, and the thousands of followers of minority religions whose marriages are not recognized by the state would be prone to criminalization. The National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) has long contended that an unintended consequence of this law reform, should it go ahead, would be the criminalization of victims of sexual violence and rape.

Rape and sexual violence in Indonesia is underreported and when cases are reported offenders are rarely successfully prosecuted. Should extramarital sex be outlawed, victims of rape will be increasingly hesitant to report their cases to law enforcement for fear of criminalization. If a victim were to report a case to law enforcement and the perpetrator claimed that the intercourse was consensual, there is a high possibility that criminalization of the victim would occur.

In the autonomous province of Aceh, extra-marital sex or zina has been made illegal through the Islamic criminal code and people who commit zina are routinely caned in public. In 2014, a gang of eight men broke into a private home where they alleged a couple was engaged in sexual relations. The eight men violently gang-raped the woman and beat the man before taking the couple to the police and reporting them for extra-marital sex. The rape victim was caned publicly for committing extra-marital sex while many of her rapists evaded arrest.

In November 2017, in what has been referred to as a case of sexual torture by Komnas Perempuan, a mob broke into a private home in Tangerang, West Java and forced an unmarried couple onto the street. Men forcefully stripped the seized woman naked and assaulted her while onlookers filmed the incident.

Naila Rizqi, a lawyer with the Community Legal Aid Institute (LBH Masyarakat) who fought against the petition in the constitutional court, explained that making extra-marital sex illegal would spark an increase in similar mob “vigilante” actions.

Mob actions whereby groups acting as moral police invade private homes and commit acts of violence against unmarried couples are already common in Indonesia. It can be expected that these mobs would interpret changes in the law as legal and moral justification for carrying out these raids.

In denying the petition, the Constitutional Court clarified that the court did not oppose the notion of the revision that was included in the petition, rather the decision was focused on arguments of jurisdiction. It was explained that it is not the role of the Constitutional Court to act as a positive legislator but the Peoples’ Representative Council (DPR) that has the responsibility to enact such changes by passing new legislation.

Human rights groups fear that these legislative changes are not far away. The draft revised criminal code (RUU KUHP) is currently being debated in the DPR and Article 484 of the code makes extra-marital sex a criminal offense punishable by five years in jail. It can be expected that the dissenting opinion of the four judges will be used by conservative groups to lobby members of the DPR and push for the retention of this article in the RUU KUHP. In response, civil society must step up campaigning and lobbying to increase awareness among members of parliament of the dangers involved in outlawing consensual sexual relations to ensure the article on extra-marital sex is removed.

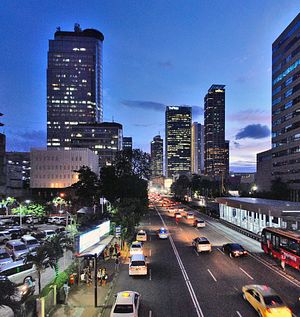

Jack Britton is a translator, researcher and freelance writer currently embedded with the Indonesian National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) in Jakarta, Indonesia.