On January 24, a shocking video did the rounds in India: of terrified school children, ducking inside their school bus, whose glass windows had been shattered. The bus, ferrying children in Gurugram, the uber-rich satellite township close to the country’s capital, had been attacked by supporters of the Shri Rajput Karni Sena, as they protested the release of the movie Padmaavat (erstwhile Padmavati).

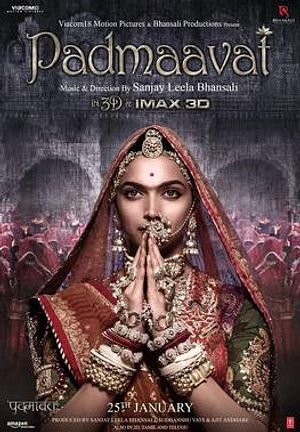

The violent saga pertaining to this opulent movie has dragged on since 2017, and has included attacks on its director, Sanjay Leela Bhansali, vandalism of the movie sets, and death threats for the lead female actor Deepika Padukone (who portrays the fictional and controversial character Queen Padmini). Days before the movie was released on January 25, violence escalated. The terrified children in the video were just a symptom of the times in an increasingly intolerant, easily offended, and violent country.

Much has happened since the movie was set to be released on December 1. The name of the movie was changed, towards dissociating legend from a work of fiction, based on the recommendations of the country’s Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), which regulates the public exhibition of movies. The exposed midriff of Padukone in the song sequence Ghoomar has also now been covered through CGI — in keeping with the objections raised by Karni Sena for depicting the queen in such a manner.

The movie is an adaptation of Padmavat, an epic poem penned in 1540, that describes the conquest of parts of the Rajput kingdom by the Muslim Turko-Afghan ruler Alauddin Khilji, who also sought to capture Queen Padmini. The queen is said to have immolated herself, in a practice known as “jauhar” to protect her honor. The tale passed into folklore was lodged in the mind of people as a true account of the battle between Khilji and the Rajputs.

This is not the first time that this tale has been attempted on the silver screen. The first attempt was in 1963, in a Tamil movie, and most recently a Hindi TV series made an attempt. Most reviews of Padmaavat yawn at its opulence, idiosyncratic of the work of director Bhansali. Yet, those who have made it to the theaters so far — in states other than Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Haryana, where film distributors are not yet screening the film — are stepping out with the realization that the movie adheres to what the Karni Sena has been throwing violent tantrums about: adulation of Rajput bravado, and the non-existence of any agency on her own life by queen Padmini, and other Rajput women. In fact, there was nothing to the imagined insinuation that the queen (played by Deepika Padukone) had an affair going on with Alauddin Khilji (portrayed by Ranveer Singh) — the original bone of contention for the Karni Sena.

That should have pacified the Karni Sena, who were invited for a preview of the movie by Bhansali. But as the Karni Sena rubbished off this invitation, its supporters — men from the upper caste Rajput community — went about vandalizing public property. The various acts of violence were committed hours after the Supreme Court refused to modify its order scrapping the ban on the film’s screening imposed by several states.

Protesters have since clashed with the police, set a car on fire (unknowingly, one that belonged to one of the protesters), all in addition to attacking the bus carrying school children. According to one report, 150 men have been arrested.

In Ahmedabad, the capital of Gujarat where Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was chief minister for 14 years, agitators vandalized a shopping mall with a cinema, and torched vehicles at three places. They dispersed only when the police opened fire. A mall was also vandalized in Haryana, a state — like Rajasthan, where majority of Rajputs hail from — infamous for instances of female foeticide and an abysmal sex ratio.

Extolling the valour of Rajput women who protected their honor by committing “jauhar” — jumping into a pit of fire to avoid rape and being captured by invading army — the patron and founder of Karni Sena, Lokendra Singh Kalvi, the son of an erstwhile minister, went on to say that 1,908 women in Rajasthan had registered their names to perform “jauhar” on January 24 if the film’s screening was not stopped.

What seems as a last straw of curtailing free speech and an open door for hooliganism to thrive, thanks to the silence of the respective state governments where the violence has taken precedence over other pressing issues, the CBFC chief Prasoon Joshi — CEO of McCann Worldgroup India, poet and screenwriter — has withdrawn his attendance from the prestigious Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF) in Rajasthan, after receiving threats from the Karni Sena.

For the children who were attacked on the bus, the blurring lines of history and legend and myth and violence only drive home the point of fear — far from the stories of valor that the violent Karni Sena, which has terrorized India, claim to keep alive.