North Korean leader Kim Jong-un visited a known site for missile research and development in December 2017, likely to provide guidance on an anticipated satellite launch in 2018, The Diplomat has learned. According to U.S. government sources who spoke to The Diplomat on the condition of anonymity, U.S. military intelligence, in addition to tracking Kim’s visit to the site, also tracked the movement of components associated with a new North Korean satellite launch vehicle (SLV) near the facility shortly after Kim’s visit. This suggests that a new North Korean satellite launch in 2018 may be a possibility; North Korea last launched a satellite, the Kwangmyongsong-4, in February 2016.

Kim Goes to Sanum-dong

The site known as the Sanum-dong Missile Research and Development Facility, or Sanum-dong Research Center (SDRC), by the U.S. intelligence community is known to host missile- and satellite-launcher-related developmental work. Kim Jong-un visited the facility, presumably to offer guidance, on December 21, three weeks after the first successful launch of the Hwasong-15 intercontinental-range ballistic missile. Kim is known to personally inspect missile- and satellite-related facilities; many, but not all, of his visits are broadcast to the world through North Korea’s state-run newspaper Rodong Sinmun and state-run Korean Central Television (KCTV).

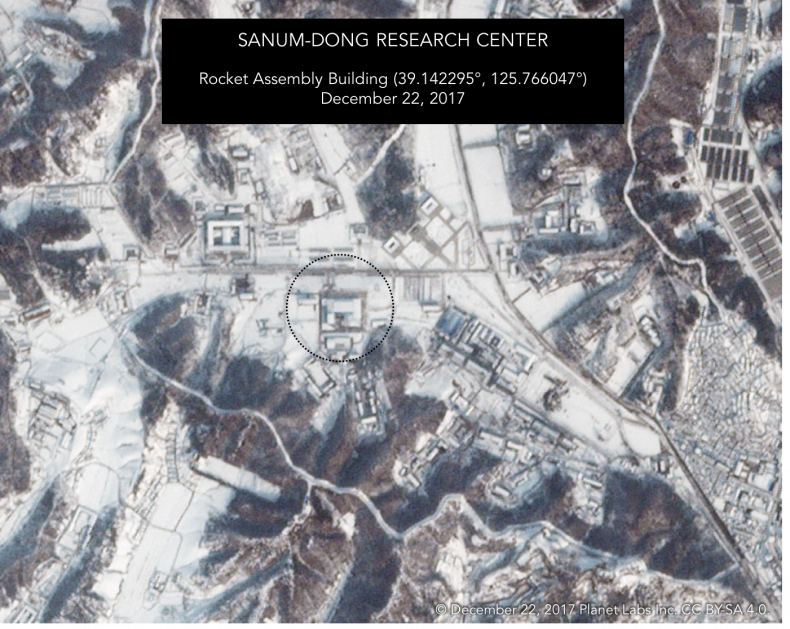

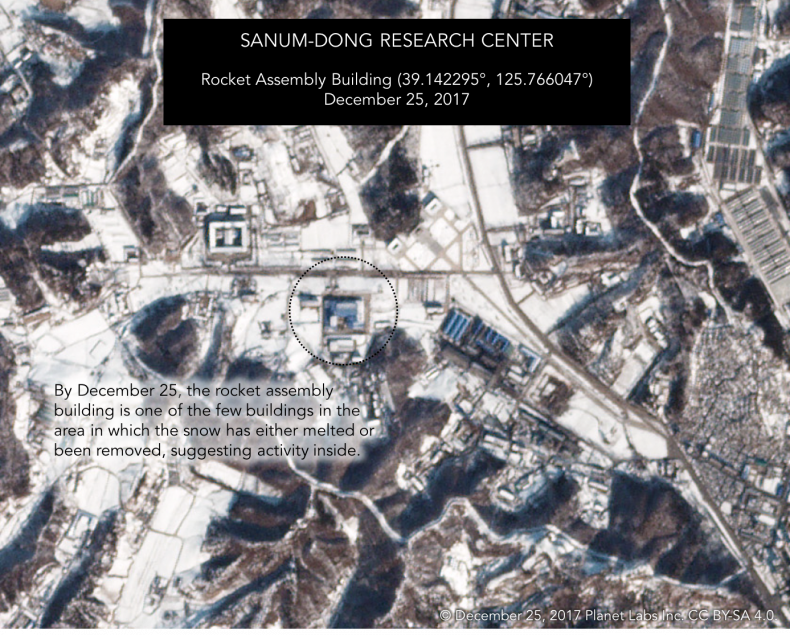

While Kim’s visit is not readily corroborated in open source resources, commercially available satellite imagery offers evidence of a sudden uptick in activity at SDRC starting on December 21. To take a closer look, The Diplomat spoke to Jeffrey Lewis, the director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. Using Planet Labs Inc.’s daily imagery of the site from the week of Kim’s visit, Lewis found a tell-tale sign of ongoing activity: disappearing snow. As late as December 22, it’s apparent that most of the SDRC facilities, including a known rocket assembly building, are initially covered in snow, at least through December 22.

After December 22, the snow is no longer visible on the rocket assembly building, suggesting to Lewis that it had either melted due to potential heat generation within the building or been intentionally removed. Nearby buildings remain snow-covered between the two dates, suggesting some sort of special activity at the rocket assembly building and ruling out a drastic change in weather as the cause for snow’s removal. Readers can pan between the two images to observe the differences here.

The building circled in the annotated image above is known to be associated with SLV and ballistic missile assembly specifically and Kim has visited it before to inspect ongoing SLV work ahead of an eventual launch. Dave Schmerler, a researcher and North Korea analyst who works with Lewis, had analyzed undated footage of Kim inspecting the February 2016 Kwangmyongsong-4 launcher at an unidentified facility and was able to geolocate the scene to this specific building at SDRC in 2016. The idea of Kim repeating an inspection of ongoing work on a new SLV in December 2017 ahead of an anticipated 2018 launch is thus more than just plausible. (Sanum-dong, unlike other sites associated with North Korea’s strategic weapons programs, is a short and convenient drive from Kim’s main residence in Pyongyang, the North Korean capital.)

Kim Jong-un inspecting the Kwangmyongsong-4 Unha-3 launcher at Sanum-dong Research Center. (Undated.) Source: KCTV screen capture.

Kim Jong-un inspecting the Kwangmyongsong-4 Unha-3 launcher at Sanum-dong Research Center. (Undated.) Source: KCTV screen capture.

Kim Jong-un inspecting the Kwangmyongsong-4 Unha-3 launcher at Sanum-dong Research Center. (Undated.) Source: KCTV screen capture.

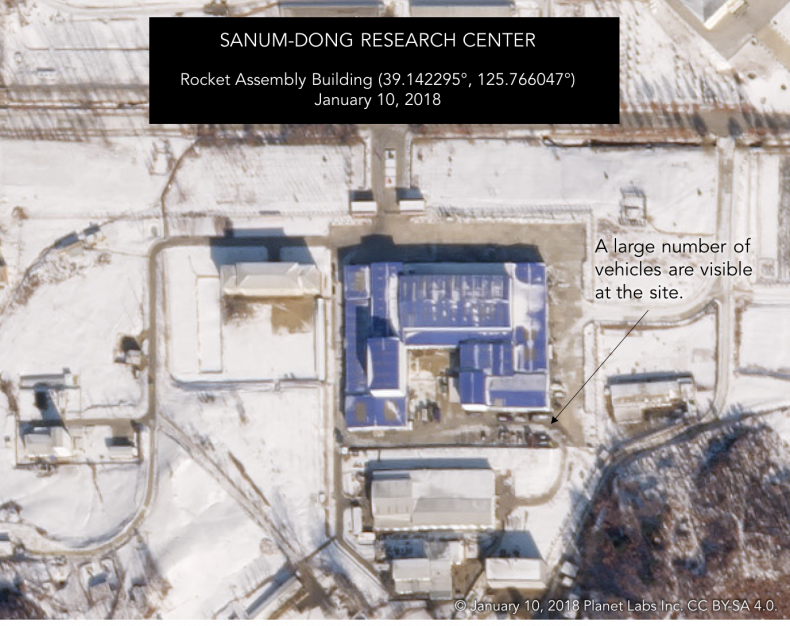

What’s more, recent high resolution satellite imagery of the SDRC site shows even greater activity since Kim’s visit. In the image below, for example, a large cluster of vehicles are visible right outside the rocket assembly building, suggesting ongoing activity. According to a U.S. government source who spoke to The Diplomat, U.S. military intelligence detected what appeared to be a heavy transporter for the first stage booster of a satellite launcher at the SDRC site on January 2, just over a week before the image below was captured.

U.S. military intelligence closely monitors SDRC throughout the year given that it is one of the primary sites for North Korea’s manufacturing of production and prototype ballistic missiles. Through 2017, U.S. military intelligence observed activity nearly weekly at SDRC; various North Korean ballistic missiles were regularly observed moving around the facility on their transporters, according to intelligence assessments shared with The Diplomat.

Context Before Kim’s Visit to Sanum-dong

Kim’s visit to SDRC also occurred shortly after North Korea convened the 8th Conference of its Munitions Industry. Footage of the conference released by KCTV showed a prominent display of the three new long-range ballistic missiles North Korea tested successfully in 2017 — the Hwasong-12/KN17 intermediate-range ballistic missile, Hwasong-14/KN20 intercontinental-range ballistic missile (ICBM), and Hwasong-15/KN22 ICBM — and what appears to be a satellite launch vehicle, most likely the Unha-3.

Secondary evidence suggestive of an upcoming satellite launch emerged first in the press in December 2017. The North Korea-focused news site NK News first featured an account from a Russian expert who had recently been to North Korea and been told by “representatives of the National Aerospace Development Administration” in November 2017 that North Korea was planning to launch “two new satellites.”

The author, Khrustalev Vladimir, provided additional detail conveyed to him by North Korean representatives, including that at least one of the two planned satellites may be considerably larger than any previous satellite payload attempted by Pyongyang. Since Vladimir’s account in NK News, North Korea’s deputy ambassador to the United Nations, Kim In-ryong, told a UN General Assembly committee on the peaceful uses of outer space that North Korea planned to launch more satellites “that can contribute to the economic development and improvement of the people’s living.”

What Kind of SLV and Satellite?

On December 30, compounding accounts of new satellites in NK News and elsewhere, Japan’s Asahi Shimbun published a report noting that Kim had directed top military officers and scientists at the munitions industry conference to complete work on a new SLV by September 2018 for a launch to coincide with the 70th anniversary celebration of the founding of North Korea in 1948 by Kim Jong-un’s grandfather, Kim Il-sung. If Kim is planning to launch a considerably larger and more ambitious satellite, timing the launch close to a prominent anniversary may make sense. (The Kwangmyongsong-4, for example, was launched slightly over a week before what would have been Kim Jong-il’s 74th birthday in 2016.)

For now, U.S. intelligence suspects that work on a new North Korean SLV may well be underway at SDRC for a potential launch in the second half of 2018. Commercially available satellite imagery establishes that activity is ongoing at Sanum-dong’s rocket assembly building. What remains unclear is what specific sort of SLV design North Korea may choose to deploy in this new launcher. Its SLVs, going back to the Taepodong-1 in the 1990s, have mostly made use of older Scud- and Nodong-derived engines. (Its most recent SLV, for instance, featured a cluster of four Nodong engines for the first stage booster.) It is possible that the twin-chambered, 80-ton engine that North Korea first tested in September 2016 and described as “a new type high-power engine of a carrier rocket for the geo-stationary satellite” may finally see use in an SLV after first appearing successfully in the Hwasong-15 ICBM. (ICBMs and SLVs, though divergent in purpose, can share design commonalities; the Soviet Union’s first ICBM, the R-7 Semyorka, would go on to launch Sputnik-1 and other satellites, for example.)

If accounts of a larger and functional satellite payload are accurate too, this SLV may require a larger payload fairing than the slender-tipped upper stages of the Unha SLVs used for the Kwangmyongsong series of satellites would permit. The December 2012 and February 2016 Unha launches successfully inserted their payloads into orbit, but neither the Kwangmyongsong-3 nor the Kwangmyongsong-4 satellites offer North Korea any known benefit. If Kim seeks to deliver a large and functional satellite to geosynchronous orbit, potentially to offer the country’s military some sort of space-based sensor capability, the final SLV may end up looking quite different from everything we’ve seen North Korea launch to date. (The Kwangmyongsong-4, the largest North Korean satellite payload to date, is estimated to have weighed as much as 200 kilograms.)

Lewis agrees. “If North Korea is going to continue its run of surprising ‘firsts,’ then the logical next step for its space program is to place a satellite in geostationary orbit,” he told The Diplomat. “That will require a bigger rocket than the Unha series.”

Conclusion

Any North Korean satellite launch in 2018 would have serious political and diplomatic consequences and be in violation of the country’s commitments under UN Security Council (UNSC) resolutions. While North Korea defends its space activities as peaceful and the legitimate right of any country, a satellite launch would assuredly invite diplomatic condemnation from the international community and possibly lead to the expansion of sanctions at the UNSC. The Trump administration has recently welcomed inter-Korean diplomacy ahead of the Winter Olympics, reducing tensions on the Korean Peninsula after a particularly tense 2017, but a new satellite launch may reverse this trend. However, a satellite launch, if scheduled for September, may be preceded by further ballistic missile testing or exercises as North Korea feels compelled to respond to the U.S.-South Korea Key Resolve exercises in April 2018.

Despite the almost assured negative consequences for the regime internationally, North Korea appears undeterred and work on a new SLV is ongoing. In defending his country’s space activities at the UN General Assembly committee in December, Kim In-ryong said his country’s will “to produce and launch artificial satellites will not be changed just because the U.S. denies it.” There’s little reason not to take Kim’s statement at face value. As U.S. intelligence and open source evidence show, North Korea is almost certainly on track to launch a new satellite in the coming year.

Ankit Panda (@nktpnd) is a senior editor at The Diplomat, where he writes on politics, security, and economics in the Asia-Pacific. The author is grateful to Jeffrey Lewis and Dave Schmerler for satellite imagery analysis to accompany this article.