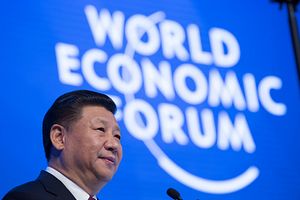

Chinese President Xi Jinping famously remarked at the 2017 World Economic Forum that “pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room; while wind and rain may be kept outside, that dark room will also block light and air.” The remark also captured the essence of Xi’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which aims not only to facilitate Chinese investment abroad, but, through progressive opening up of the Chinese market, allows more foreign enterprises to invest in China. In his Belt and Road Summit Speech in May 2017, Xi stated, “We should build the Belt and Road into a road of opening up. Opening up brings progress while isolation results in backwardness.”

Up to now however, all evidence suggests that China is failing to make the BRI a two-way street. In reality it remains very difficult for foreigners to gain access to Chinese markets. Unless greater attempts to liberalize are made soon, this asymmetric access could well jeopardize the success of the BRI.

The asymmetry is highlighted when we look at foreign direct investment (FDI) flows. In 2017, Chinese outward FDI amounted to $111 billion, more than four times higher than in 2012. In contrast, inward FDI flows into China amounted to less than $40 billion once investments originating from Hong Kong were stripped out.

This discrepancy is primarily a result of China’s reluctance to open its markets. The Chinese government divides inward investments into three categories; encouraged, restricted, or prohibited. However, even investments into encouraged sectors face significant obstacles, for example through minority stake equity caps and limited voting rights.

Despite some liberalization occurring in recent months, the European Chamber of Commerce has described the changes as falling way short of expectations. Consequently, both the United States and the European Union have escalated their long-standing concerns with Chinese FDI and are adopting tougher stances.

The Trump administration is considering establishing a reciprocity system, which would see Chinese investors face the same restrictions in the United States as U.S. investors face in China. While the proposal may well run into legal challenges, it nevertheless shows that Washington is becoming more assertive in addressing its economic relations with China. The European Commission, following Chinese FDI into the EU in 2016 of €75 billion – more than the previous ten years combined – has also proposed a mechanism through which FDI projects originating from outside the EU are evaluated centrally. Moreover, Germany, France, and Italy have raised specific concerns with Chinese investment in the EU. Along with developing more defenses against Chinese investments, countries are also developing counterinitiatives. For example, recent reports claim that the United States, Japan, India, and Australia are considering creating an alternative to the BRI.

With this growing backlash against Chinese investors, motivated by both security concerns and the lack of reciprocity, the Chinese government must ask themselves what this means for the prospects of BRI. Core to the BRI is enabling Chinese firms to find new markets abroad; to both sell goods and construct overseas infrastructure. If more countries begin to shield themselves against Chinese economic expansionism, then this core objective would become much harder to achieve. Moreover, the ability for Chinese companies to acquire know-how and catch-up technologically with foreign competitors would be greatly slowed down and hinder the aims of the “Made in China 2025” strategy.

Politically, China’s ability to muster global support for its re-emergence is based on presenting the BRI as an opportunity for shared benefit rather than a competitive threat following zero-sum logic. Without economic reciprocity however, China’s narrative of the “Silk Road Spirit,” through which all countries benefit, at best loses credibility and at worst seems hypocritical. Instead of reflecting Xi’s comments in Davos, it would seem that right now China wants to simultaneously be in its dark room whilst benefiting from light and air. Yet the growing global backlash proves that China cannot have it both ways.

Grzegorz Stec is an Associate Researcher at European Institute for Asian Studies (EIAS) in Brussels and a Yenching Scholar at Peking University. He is a co-founder of beltandroad.blog.