So far, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has focused on investments, particularly infrastructure projects, in Central and Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe. However, the Chinese government’s Vision and Action Plan also foresees the provision of economic opportunities to regions in Northeast Asia. Specifically, three northern Chinese provinces — Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang — are positioned to become part of a Northeast Asian economic zone that could link Russia, Mongolia, and possibly even the Korean Peninsula. However, given the increased tensions on the peninsula after North Korea’s nuclear tests and deepened U.S. sanctions, the room for cooperation between China, South Korea, and North Korea has shrunk even further – or has it?

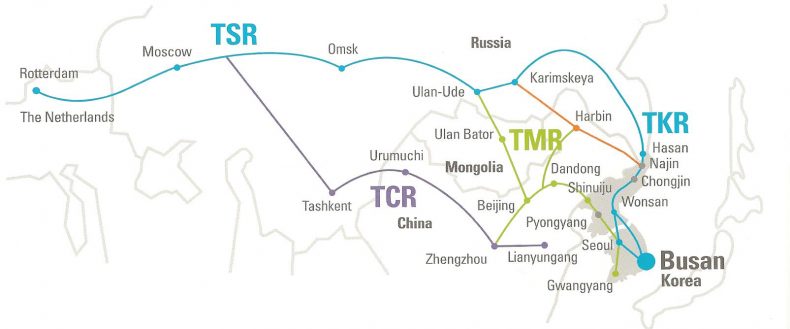

South Korea developed its own “Eurasia initiative” (EAI) in 2013, the same year that the BRI was announced. EAI is also based on economic cooperation in Eurasia through infrastructure projects, such as the trans-Korean railway, that ultimately hope to promote peace to the Korean Peninsula. By doing so, South Korea could also access train routes over the Eurasian landmass, reducing the logistics costs of its exports to Europe by up to 30 percent.

Yet, despite a recent breakthrough in Olympics cooperation, it seems highly unlikely that such a railway will be completed in the near future. While the initiative foresaw the elimination of trade barriers and creation of special economic zones that could benefit the North Korean economy, Pyongyang continues to be too protectionist and concerned with survival of the regime to allow for regional economic cooperation and opening up. Particularly, since new sanctions were enhanced in early 2016 as a response to North Korea’s fourth nuclear test, talks on the EAI have stalled.

Source: itrailnews.co.kr

While both the BRI and EAI should be compatible with each other from the perspective of economic integration and cooperation, ultimately each country’s visions for national and regional security are conflicting. The BRI excludes any remarks about the development of the Korean Peninsula, perhaps due to the Chinese government’s desire to maintain the status quo of a divided Korea and in its assumption that North Korea might resist any call for regionalization. The underlying goal of the EAI, on the other hand, is to promote cooperation on the Korean Peninsula in order to create a more stable security environment for South Korea. By creating new access to the Eurasian market, South Korea hoped to create a domestic boom, while becoming less dependent on trade with China and the United States. At the same time, the initiative foresaw North Korea’s economic integration into the region, which might trigger changes for the country.

Comparing the outlook of the two initiatives for the peninsula, it seems that they cannot coexist at this state without creating further tensions in the region. If China does not include South Korea in its initiative, but approaches North Korea for trade, then relations between Seoul and Beijing might deteriorate. Likewise, China will not be too pleased if the South pushes forward with an initiative that diminishes China’s economic grip on the peninsula.

Nevertheless, there might still be a window for greater economic cooperation. Clearly, China is aiming to economically regenerate its northeastern provinces and improve cross-border trade; a special economic zone in the region that connects to the Far East would be one way of promoting this agenda. South Korea, in turn, could look for areas with greater synergies between its EAI and China’s BRI — especially in terms of infrastructure and industrial investments. If South Korea and China manage to align some of their economic and strategic interests, this could create more room for a dialogue on geopolitical aspects of how both initiatives could stabilize the region.

While China and South Korea have their differences, they are not insurmountable. It is, instead, the actions of the North Korean regime that continue to pose an obstacle to achieving the final piece of the Eurasian integration puzzle. Long-term projects such as the EAI and BRI require long-term, stable cooperation, as they are implemented over the years to come. Despite accelerated diplomatic talks on all sides over the past year, North Korea has continuously tested and built up its nuclear arsenal, and consequently the possibility for trade with either South Korea or China has declined significantly.

China even invited North Korea to its first Belt and Road Summit in May 2017. Previously, the North underwent slow economic reforms that allowed for gradual increases in trade and entrepreneurship in limited areas, and this could certainly have been a starting point for talks point during the summit. However, given the backdrop of intensified international sanctions as well as North Korea’s foreign policy, any meaningful cooperation through the BRI was impossible.

With North Korea continuing to play a mixed strategy, where it fluctuates between threatening the international community, and occasionally showing desires to cooperate, there will no doubt be opportunities to engage through both the EAI and BRI. Policymakers must seize those opportunities; the economic cooperation promoted by both initiatives could really spark an opportunity for increased connectivity and stability across the peninsula. Yet, the reality remains that no full-fledged agreement will be made until either the nuclear issue is resolved or the geostrategic interests of China and South Korea converge. This is why both countries should look for strategic synergies and put forward a proposal on how to best merge both initiatives in order to create a more stable Korean Peninsula. If both countries can find a common denominator and outline economic opportunities for Pyongyang, perhaps North Korea would be more willing to make concessions on regional cooperation and integration.

Maximilian Römer is a MPP candidate at the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin and a Yenching Scholar at Peking University in China.