China has long been involved in Arctic affairs and has become an important player in the region in recent years. But without a clearly articulated Arctic policy, China’s frontline diplomacy has lacked guidance, leading other countries to be suspicious of its intentions on key issues.

China’s publication of an Arctic Policy White Paper on January 26 will do a lot to resolve these problems. It was welcomed by polar scientists, countries involved in Arctic governance, and interested organizations that have long called for China to stake out a clear position.

An Important Stakeholder

China defines itself in the white paper as an “important stakeholder” in Arctic affairs, noting that geographically it is close to the Arctic although not an Arctic nation.

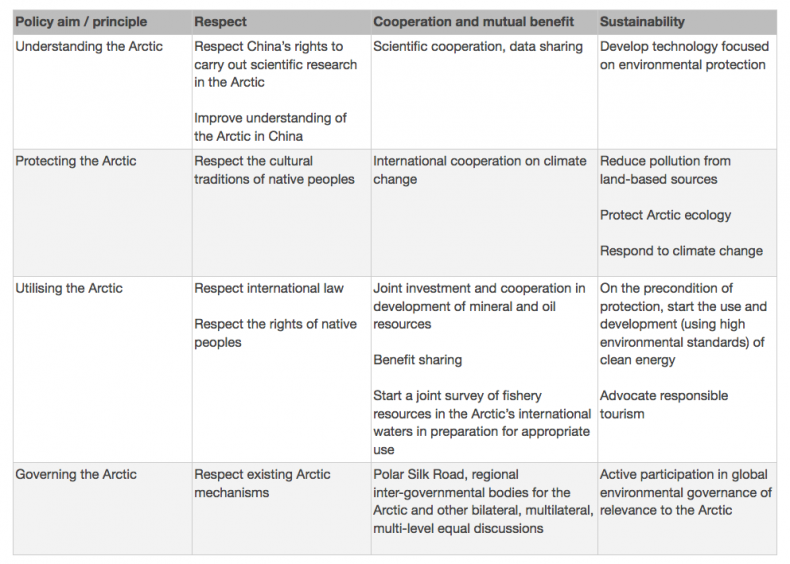

As a self-described stakeholder, China sets out principles of “respect, cooperation, mutual benefit, and sustainability.” Respect refers to the rights of Arctic nations under international law, while also requiring that the interests of China and international society are respected by the Arctic nations. Mutual benefit is a long-standing value in Chinese diplomacy, while sustainability refers to a balance between protection and utilization.

The table below puts the policy stances of Section 4 of the white paper within the framework of its policy aims and principles:

Protecting the Arctic Environment

The white paper expends considerable ink on environmental protection and sustainable development, with the following highlights:

China is promoting a global, rather than regional, approach to the Arctic.

Given the importance of climate change on the Arctic, the white paper refers several times to ideas such as “the overall interests of international society” and “the shared fate of humanity.” While actual policies focus on international cooperation on climate change, developing renewable energy in the Arctic, and actively participating in global governance of the Arctic.

“Understanding the Arctic” is the foundation of all policy, which means China will rely on scientific research in its decision-making.

Late last year five Arctic nations and five other nations, including China, agreed to a moratorium on fishing in international Arctic waters. The idea behind the agreement was to carry out a survey and research, so that any future commercial development would have a scientific basis. This cautious approach is unprecedented in global fisheries management.

China wants citizens to participate in Arctic affairs.

This includes creating a center for people to learn about the Arctic, and describing a “low-carbon, eco-friendly and responsible” approach to developing tourism. During the Antarctic Treaty conference last year, 10 Chinese travel companies launched an initiative on responsible Chinese polar tourism, based on the understanding that responsible tourism can build links between the Chinese people and the Poles, inspiring them to help protect both the Poles, climate, and enrich China’s participation in polar governance.

Polar Worries

Although the white paper covers protection of the polar environment, it is not time to celebrate yet. There are still concerns about development and climate risks, and respecting the wishes of native peoples.

Some Arctic nations have welcomed China to the Arctic governance “club,” in large part because they are keen to develop the region but lack the resources to do so. China’s participation may bring to the table much needed investment in oil and gas exploration and infrastructure building. The white paper makes no effort to hide China’s interest in the region’s economic development, which seems inevitable.

Although China speaks of raising development standards, the Arctic has its own specific risks and therefore requires extra caution.

In November 2017, a Russian state-owned tanker became trapped in sea ice on the Northern Sea Route and had to be rescued by the Yamal, a nuclear-powered icebreaker. If the ice had crushed the tanker’s hull, the consequences of an oil spill would have been grave. Such risks will increase as Arctic shipping opens up and oil and gas resources are exploited.

The methane contained in the Arctic permafrost is a climate time bomb. There are 50 billion tonnes of methane, in the form of hydrates, on the Siberian Arctic continental shelf. When the sea bed warms, either gradually or suddenly, within the next 50 years, that methane is likely to be released.

More methane in the atmosphere means faster global warming, which will further accelerate warming in the Arctic, increasing the rate of sea ice loss, reducing reflection of solar energy and leading to faster melting of the Greenland ice cap. Glaciers distant from the Arctic will also melt. This vicious circle is irreversible. So far, there is little to no discussion about how to mitigate the effects on the Arctic.

Finally, while the white paper aims to “respect the culture, traditions and interests of the native peoples,” this may prove difficult in practice.

The 2011 Circumpolar Inuit Declaration on Resource Development Principles in Inuit Nunaat gives the Inuit people the right to be informed and heard when decisions on resource development are being made and requires their agreement before development takes place. That means resource projects will have to work carefully with the Inuit, and any project may face criticism for “damaging local traditions.”

In the past, local traditions have also been in conflict with environmental protection.

In 2009, the European Union (EU) bowed to pressure from animal protection groups and banned the trade in seal fur. Canadian Inuit groups, fearing this would damage their traditional seal hunting practices, sued the EU. In 2011 the General Court and the EU Court of Justice rejected the suit, which had been brought by 17 Inuit groups, including the ITK, Canada’s biggest Inuit group. This case shows how the rights of native peoples are not always aligned with those of environmental protection.

Overall, China’s white paper indicates the country will take an open and active approach to participation in Arctic governance. This may speed up development of the Arctic, but China’s ideal of a “human commonwealth” and its contributions to scientific research and governance in the Arctic can strengthen international society’s response to the grave challenges it faces.

This post was originally published by chinadialogue and appears with kind permission.

Chen Jiliang is a researcher at Greenovation Hub, a non-governmental organisation based in Beijing.