Along a mountain highway in southern Kyrgyzstan, a herder moves his horses down a paved road winding from the high Alay Valley – a now-remote region that was once a key channel of the ancient Silk Road. This road will eventually terminate at the city of Osh in Fergana, a large basin spanning the international borders of three modern nations – Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. One of the most beautiful and agriculturally rich regions in Central Asia, today Fergana is messily divided between the three countries, with piecemeal borders sometimes tracing topographical features or even demographic patterns. In recent years, tensions have run high and have occasionally flared into violence, as the region struggles to redefine itself in the post-Soviet era.

Although modern sociopolitical developments have now made it difficult to traverse the region, for most of human history this mountainous area served as a natural highway for the movements of people, animals, and plants. Dr. Svetlana Shnaider, a researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Novosibirsk, directs a research project at the archaeological site of Obishir – an ancient rockshelter in southern Fergana. Colleagues at her institute have found evidence of human occupation of Central Asia dating back at least 120,000 years. “Central Asia was an important corridor for the movement of the first peoples across the continent,” she says.

The Fergana Valley, bracketed by high mountains, is one of the richest agricultural regions in Central Asia. Photo by William Taylor.

Here, anatomically modern humans may have encountered both Neanderthals and the recently discovered Denisovan humans as they dispersed out of Africa. The mountains act as a magnet for rainfall and biodiversity, providing rich plant and animal resources in an otherwise dry environment. Working closely with Dr. Aida Abdykanova at the American University of Central Asia, Shnaider’s work has revealed cultural connections between Central Asia and faraway areas like the Levant and the Zagros Mountains following the last Ice Age. From the earliest days of human history, it seems, the region has facilitated the movement of people across the Eurasian interior.

Dr. Svetlana Shnaider, Dr. Andrei Krivoshapkin, and Dr. M Krajcarz analyze a cultural layer at the Epipaleolithic rockshelter of Obishir-V. Photo byM. Krajcarz.

Along with humans, Central Asia has also funneled other organisms like plants and animals between East and West – leaving a major fingerprint on human history. The area’s dry climate and high mountains, such as the Pamir, Tien Shan, and Alay Mountains, make it well suited for certain kinds of agriculture. Perhaps as a result, Central Asia boasts some of the earliest evidence for long-distance movement of domestic plants between eastern and western Eurasia – a phenomenon archaeologists refer to as “proto-globalization.”

Dr. Robert Spengler is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany. He specializes in paleobotany, the study of ancient plant remains. Spengler’s work has shown that for at least 4,000 years, the mountains of Central Asia (and the people who lived in them) helped to move domestic crops such as millet, wheat, barley, and rice into parts of the continent where they were previously unknown. “As early as the 3rd millennium BCE,” he says, “exchange in crop varieties across Central Asia shaped the economies of the ancient world.” During the mid-first millennium BCE, a traveler moving through Central Asia might have been surprised to find grapevines and be offered a local wine. By the time of the Roman Empire, increasingly sophisticated Silk Road trade networks transported indigenous fruits like the apple and the pear as far away as China and the Mediterranean.

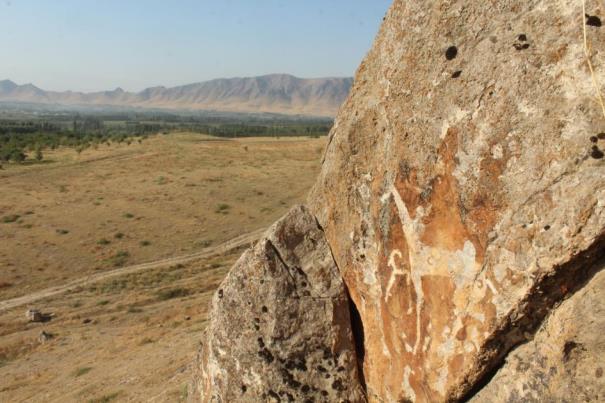

An Iron Age petroglyph shows a tall Fergana horse at an archaeological site in Kyrgyzstan. Photo by William Taylor

Exchange of domestic animals, too – particularly Central Asian horses – began to influence the social and economic landscape of a vast stretch of the Eurasian continent. Recent genomic studies suggest that Central Asian horsemen already practiced selective breeding by approximately 600 BCE, developing horses that were stronger and with greater endurance than ever before. By the second century BCE, people living in Fergana had developed a landrace of tall, powerful horses supposed to have sweat blood – perhaps caused by a small parasite found in Central Asia and other areas of the Old World.

Around this time, China’s Western Han dynasty became embroiled in what was to be a centuries-long struggle with the Xiongnu (perhaps most familiar to some readers as the barbarous villains from Disney’s Mulan). Beleaguered by Xiongnu raiders from the steppes of Mongolia, the Han were desperate for quality horses. Word began to trickle in of the rare, powerful horses from Fergana. The Chinese Emperor became convince that these noble beasts were the legendary Tian Ma (天馬), or “heavenly horses,” descended from dragons and linked with immortality. After a series of Han military campaigns to Central Asia checkered by heavy losses and brutal travel conditions, a contingent of soldiers returned to the emperor with 1,000 Fergana horses. Over the coming centuries, demand for Central Asia’s strong and magnificent horses became one of the major economic drivers of the Silk Road networks linking East and West.

A Chinese ceramic figurine, dated to the Tang Dynasty (circa 600-900 CE) depicts a Fergana horse. From collections at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia. Photo by William Taylor.

In 2018, plants from around the globe can be bought at most neighborhood grocery stores, and horses have become little more than a novelty for those living in urban centers. However, a closer look shows that movements in people, plants, and animals through Central Asia had a lasting impact on our modern world.

A roadside market near the city of Osh shows an abundance of fruits and vegetables for sale. Photo: W. Taylor

“What you see sold in the markets today are the result of several millennia of cultural exchange and interaction,” says Spengler. “For example, in Bukhara [Uzbekistan], you’ll see bananas being sold alongside local varieties of melons that may be thousands of years old.”

The heavenly horses, too, are far from extinct. Many consider the Akhal-Teke horse to be the descendant of the original Fergana horses. Every two years, Kyrgyzstan hosts the World Nomad Games – a global competition including equestrian sports like horse racing and Kok-boru – where the athletic prowess of the region’s horses is on full display. Kyrgyzstan took first place in the 2016 competition.

Increasingly, research is showing that the networks and processes that structure our world today are linked to developments in the past. With China gearing up for a several hundred billion dollar “New Silk Road” infrastructure project, understanding the corridors of movement that brought the first humans through the high mountains, and later couriered domestic plants and animals across Central Asia, are as relevant now as they have ever been.

“If we want to understand our globalized world, and the way it works,” Shnaider says, “we have to look even closer at the past.”

William Taylor is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, whose research explores ancient human-environmental interactions