The establishment of a Kra Canal in Thailand may soon become a reality as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The canal would permit ships to bypass the Malacca Strait, a crucial maritime chokepoint, amplifying the strategic significance of the project.

Throughout history, there have been multiple attempts by the Thai monarchy and European colonists to capitalize on the commercial and strategic importance of the region by constructing a canal across the narrow isthmus that connects Thailand to the Malay peninsula. In recent times, China’s global vision of a new Maritime Silk Road has renewed the attention on the possibility of developing the Kra Canal. The modern Kra or Thai Canal project would be connected to the various Chinese infrastructure and connectivity projects in the region.

The maritime portion of the BRI is an ambitious connectivity project that aims at linking Southeast Asia to Europe through the Indian Ocean. In the last two decades, the construction of new ports and maritime facilities has contributed to the increasing competition among nations in the Indian Ocean region. As China continues to expand its presence across the maritime domain, the establishment of infrastructure projects, like the Kra Canal, is likely to influence the new emerging security architecture in the Indo-Pacific.

Most recently, the Thai-Chinese Cultural and Economic Association and the European Association for Business and Commerce participated in a conference on the Kra Canal in Bangkok on September 2017 and a follow-up event on February 1, 2018, signaling a greater interest in executing the project.

Historical Significance

The strategic purpose of the canal was initially recognized in the 19th century under King Rama I and King Rama IV as a quick way to send Thai troops to counter Burmese invaders to the north of Thailand. Under King Rama V, the French sent Ferdinand de Lesseps, the engineer credited with building the Suez Canal, to raise the possibility of constructing the Kra Canal again. But, in an effort to appease the British who already had a strong foothold in the Malacca Strait, especially Singapore, the Thai King declined the offer.

After World War II, Thailand was forced to sign Article 7 of the Anglo-Thai treaty of 1946, which prevented them from constructing the canal in an effort to ensure international political stability. It wasn’t widely discussed again until the 1980s, when the potential of the project was highlighted by the American-led Executive Intelligence Review (EIR) and the Fusion Energy Foundation as a major economic advantage to an increasingly industrialized and globalized world. The report included the long-term advantage of the canal to Thailand and its neighbors.

The onset of the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s provided a major setback for the Kra project and it wasn’t until Yingluck Shinawatra’s prime ministerial term that the canal came back to the limelight. Yingluck Shinawatra’s commitment to infrastructure and development projects to boost the country’s economy reinstated the country’s positive approach to the possibility of the Kra Canal.

The Canal as a Part of BRI

The possibility of the Kra Canal becoming a reality has been greatly increased by China’s Maritime Silk Road initiative and the Thai Canal Association (TCA), a group of influential former top brass soldiers advocating for the project. Based on reports, the canal will cost approximately $28 billion and take a decade to complete. China is reportedly willing to supply the financial and technological support to Thailand in hopes that the Thai canal reaches fruition.

The new Thai Canal project comprises two portions. The first portion is seen as a counter to the “Malacca Dilemma.” The canal will link the South China Sea to the Andaman Sea, connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean respectively, drastically diminishing transit time across the busiest maritime shipping route. Chinese companies are extremely interested in speeding up the project as over 80 percent of Chinese oil imports flow pass through the Malacca Strait. The second portion is the establishment of a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). The new zone includes the addition of cities and artificial islands, which will enhance new industries and infrastructure in the region. This would make Thailand into a “logistic hub” and link Thailand to countries from all over the world.

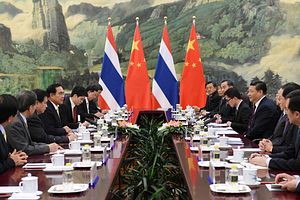

While the Chinese government has refrained from making any official claims, reports state that China and Thailand signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on the canal project in Guangzhou in 2015. The MoU was signed by the China-Thailand Kra Infrastructure Investment and Development company and Asia Union Group. Apart from the Chinese interests in the region, however, the Thai government is trying to attract other international funding from Japan, South Korea, India, and ASEAN countries.

Challenges

While the construction of the canal is a lucrative idea with significant strategic implications, it is not without challenges. The major concerns associated with the construction of the project are environmental effects and Thai national security. The division of the isthmus has considerable environmental implications on the flora and fauna of the region. Chinese counterparts expect the Kra Canal to be similar to other Chinese megaprojects like the Three Gorges Dam in China.

A serious concern associated with the construction of the canal is its possible impact on Thai sovereignty and security. The southern portion of the country (south of the proposed canal) has seen an increasing divide between Thai Buddhists and Thailand’s Malay Muslims. The historical animosity between the two groups stems from 1902, when Thailand first annexed the independent state of Patani. In the last few decades, due to the mismanagement of the government, the southern part of the country has seen an increase in insurgency attacks. The construction of the Kra Canal would further exacerbate the volatile region, creating further divisions within the country.

Rhea Menon is a researcher at Carnegie India.