India’s space organization, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), launched its heaviest communication satellite, the GSAT 6A, on March 29. The satellite was carried on GSLV-F08 rocket from the second launch pad at the Satish Dhawan Space Center at Sriharikota in South India.

GSLV-F08 rocket itself was on its 12th mission, and the sixth using an indigenously developed cryogenic engine. Putting the satellite into the right orbit (a geosynchronous orbit above 36,000 kilometers) was to take place subsequently in what is called an “orbit raising operation.” The first of the three such operations took place on March 30, and the second operation was successfully conducted on March 31.

But then the ISRO confirmed on April 1 that it had lost communication with the satellite, four minutes after the second orbit raising operation. Even several hours after losing the communication with the satellite, ISRO officials maintained that they may still be able to reconnect, saying that they know the “approximate location of the satellite in space by using other satellites and other resources.”

It is suspected that the loss of communications links is due to a power failure. This could have been something like a short-circuit, leading to what the experts call “‘loss of lock’ or loss of contact with the ground station.” The Chairman of ISRO, Dr. Sivan, too, pointed to a recent similar incident in Russia, when the Russians lost links with a communication satellite that they were launching for Angola (Angosat-1).

To be sure, this is not entirely new: there had been a number of incidents in the 1980s and 1990s where Indian satellite launches have experienced power failures. Since then, however, the ISRO appeared to have fixed the problem.

The latest incident with the GSAT 6A suggests this might not be the case. This is not without consequence. Reports suggest that if ISRO is unable to establish communication links with GSAT 6A, it could end up floating in space as debris but fully loaded debris, with fuel for its orbit raising and for its full life cycle of 10 years.

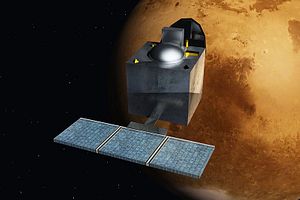

The GSAT 6A satellite, built at a cost of 2.7 billion Indian rupees ($41.5 million), was to last 10 years and was meant as a backup for the GSAT 6, which was launched three years ago. GSAT 6A is a communication satellite meant to offer mobile communication for India with multi-band coverage facility – five beams in S-band and one in C-band.

There were high hopes placed on GSAT 6A. With a 6-meter unfurlable S-band antenna, the biggest used yet by the ISRO, GSAT 6A was supposed to offer better capacity and thereby strengthen the communication system. The satellite was also to help mobile communication throughout the country, particularly in India’s remote areas. Beyond this, the satellite was also important for the Indian military, which was hoping to enhance its own communication network.

This launch itself was also important because it tested the ISRO’s modified, High Thrust Vikas booster engines, which generated about six percent more thrust than previous Vikas engines. This time, the new Vikas engines were used only in the second stage; in the future, the four first stage booster engines will also be the high thrust boosters.

How significant is this failure given all of this?

Media accounts have noted that this is technically the second major failure in the last six months, and the first since Dr. Sivan took over as the ISRO Chairman. The launch was certainly scheduled prior to his taking office. The previous failure involved a PSLV C-39 carrying India’s navigation satellite, IRNSS-1H, due to a problem with the heat shield. The next navigation satellite IRNSS-1I, the eighth satellite to join the NavIC navigation satellite constellation, will be launched on April 12 as per schedule.

The deeper question, beyond the one of blame and individuals, is whether the failure of the GSAT 6A will have a longer-term impact on ISRO’s credibility as a reliable satellite launcher. Considering that there do not appear to have been any problems with the launch itself, or the new high-thrust Vikas booster, the ISRO can salvage something even if they are not able to re-establish communication with the satellite. Hopefully, this will mean that the GSLV can achieve the kind of reliability that the PSLV has achieved, which has made the latter a tried and tested workhorse of the ISRO.

This failure, however, is not without its costs. The first part of this is the simple reality that the ISRO, which itself works on a shoestring budget, cannot afford failures. Beyond that, the Indian military will also now have to wait longer to upgrade its communications. But most of all, failures like these hurt the ISROs reputation as a credible space agency that can launch satellites in a cost-effective manner. That is what will worry it the most.