“Pay half of the book’s price, read it and return it to me,” suggests the pavement bookseller to the unconvinced passerby. Both happen to be women and the venue is Daryaganj, an area of Delhi famous for its Sunday market of used books. The offer could have been unusual, but this overheard dialogue signals that I have just entered the zone of deep bargains.

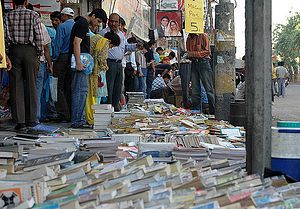

On the visual level, the bazaar is everything but dazzling. Every Sunday the book merchants lay out mats – or whatever material they happen to have – straight on the pavements, between small shops, the busy street, and the small streams of dirt that flow along the verges of the roads. Most assemble the books in neat rows, but some put them in stacks that lean against the walls of the back-alley buildings, and a few simply leave their belongings in unruly piles. Most trade on the pavement: during the Sunday flea market only a few sellers reside in real shops.

Yet, after my first visit to Daryaganj I returned with some 30 books. My trophies included editions of the famous chronicles of the Mughal empire: the Baburnama, the Ain-i-Akbari, the Akbarnama, and much more.

Daryaganj is a flea market, but it offers much more than just leftovers. Impoverished people are often forced to sell things from their houses, as if parting with the memories of their past, happier lives. We see them in India, I see them in Poland, we all witness them in so many places, offering random, used stuff, sometimes bordering on plain rubbish. The old family treasures become cheap material sold at the price of bread (and for the sake of earning bread) – and only by luck they can become somebody else’s treasures. It’s sad and unjust and I am not saying it does not happen at Daryaganj as well. But at the same time Daryaganj is so much more.

The eminent Indian historian Ramchandra Guha, who wrote a piece praising and defending the book market not long ago, considers Daryaganj one of the few such places left in India’s biggest cities, and one which “remains in a class of its own.” Guha also pointed out that the renowned Indian sociologist Shiv Vishwanathan “once even dedicated a scholarly essay to this book bazaar; which, in the absence of a world-class library in India’s capital city, had provided him the resources with which to conduct his research!” Obviously this may greatly depend on what you need and what you can get there: not every scholar may be that lucky and Daryaganj can not serve as a proper research library. Daryaganj is not a gem, but you can find gems hidden within its twisted folds, if you look hard and are lucky.

To be frank, nowadays it is easier to collect school textbooks and equip a child with stationery at Daryaganj then to search for really old books. Many of the publications are actually quite or entirely new, packed and looking like they arrived straight from the bookstore. And you can also buy copybooks by weight – for instance, for a mere 100 rupees (less than $2) per kilogram. “First time in the world books sold by weight, “ announced the banner on one of the shops, in a somewhat exaggerated fashion.

Contrary to Guha’s and Vishwanathan’s experiences, during my last visit Daryaganj I did not find the books I needed for my research but they were so old and rare that I would be surprised if they would be there. But looking for the dusty oldies is always a matter of very specific hobbies and chance. One of the most amusing things I noticed at Daryaganj was a booklet about a Chinese hotel (yes, written entirely in Chinese and no, it wasn’t a hotel in Beijing or Shanghai).

But it’s worth adding that while the flea market takes place on Sundays, the books rule the area throughout the week. Opposite the pavement bazaar, on the other side of the main road, stands a neighborhood that hides Ansari road, a street with two rows of proper bookstores. More shops line up along the Asaf Ali Road, the main street that goes along a part of the pavement market. New books dominate the working days; the old books come out on Sundays. The flea market may not be a world class library but combined with Daryaganj’s many bookstores it could count as one.

For me, visiting Daryaganj was also finding a piece of the “Old World.” Not in the sense that the publications I purchased were dated and torn, not because I picked historical volumes, and not only because Daryaganj happens to be located in Old Delhi. This was the “Old World” because the books were sold with nothing to promote them but their own value. When I took the cumbersome baggage of 30 books back home by bus, they were not held in any designer shopping bags but brought together into two bulky columns with a simple rope – apparently the only way of packing the seller could offer. It is the same “Old World” in which – 14 years ago – the man selling tea at the Delhi government school in which I studied used to brew it in a simple pot over a small gas stove. There was no restaurant, no canteen, and no soft drink vending machine in the school at that time. No advertising, no investment, and no fashion: only the man and his work to speak for itself, just like with the value of the books sold from the pavement bazaar.

Of course, the phrase “Old World” is a generalization. There are always many “old” and “new” things and many ways of understanding of what is “old” and “new.” It is easier to say what Daryaganj is not: it is not an outlet of a chain of fancy stores, it is not a shopping mall, and it is not an attraction for tourists and the middle classes dressed up as a shop with traditional products.

In January 2018, reports emerged that Daryaganj was closed and there was gossip that it may not reopen again. Would another part of the “Old World” disappear? My intuition suggested to wait – and indeed the book market has returned after some time. In May 2018 I found the Daryaganj flea market alive and kicking, perhaps as vibrant as I first saw it in 2004. There is, however, always a risk that due to my infrequent visits I am missing some important changes.

I do not doubt, however, that places such as this may face a threat of closure or gradual death. Shopping malls may not take over the trade from them as there is only a partial overlap in products. E-commerce may pose some challenges, but will only entice away the middle class customers that have constant access to the web and possess virtual cash (however awkward that may sound). And herein one finds the the crucial factors behind the market’s staying power: lack of financial resources (that allow one to buy new, original, and more expensive things) and of widespread access to technology (which allows to make purchases in different ways). It’s aspects like these which may keep places like Daryaganj alive, at least for some time. This flea market will hopefully not flee too quickly.