In his new book When the Center Held, Donald Rumsfeld calls the “successful handling” of the Mayaguez Incident, the last battle of the Vietnam War, “a turning point” for President Gerald Ford because it forced him “to demonstrate his command at a time of international crisis.” Not all share this rosy and revisionist view of the disastrous and unnecessary search and rescue operation that left 41 American servicemen dead.

Foremost among the skeptics is Mayaguez survivor and decorated Marine Scout Sniper Fofo Tuitele whose conspicuous and overlooked heroism during the battle is now the subject of a congressional investigation. “We lost 41 and saved 40. What kind of trade is that? That’s what bothers me still,” said Tuitele. “It didn’t have to happen like that. It all sounded good on paper, but it was a disaster.”

Rumsfeld goes on to make a Freudian slip and erroneously claim that only three Americans died during the operation (41 American servicemen died). Is he referring to the three Marines — Joseph Hargrove, Gary Hall, and Danny Marshall — who were left behind and survived for days before they were captured and killed?

Former U.S. Marine Larry Barnett holds photos of, from the left, Lance Cpl. Joseph Hargrove, Pfc Gary Hall, and Pvt Danny Marshall, inside his home in Urbana, Ohio (Feb. 7, 2001). AP Photo by Al Behrman.

Two weeks after the fall of Saigon, on May 12, 1975, a Khmer Rouge patrol boat seized the U.S. merchant ship SS Mayaguez and its crew in Cambodian waters. President Ford, goaded by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, believed that the ship’s seizure provided an opportunity for the United States “to prove that others will be worse off if they tackle us, and not that they can return to the status quo. It is not enough to get the ship’s release.” One Pentagon official told Newsweek at the time, “Henry Kissinger was determined to give the Khmer Rouge a bloody nose.”

Three days later, eight helicopters carrying almost 200 Marines left Utapao, Thailand for Cambodia’s Koh Tang Island, where they believed the ship’s crew was being held. Minutes before the first helicopters landed, Ford received word that the Cambodians had released the ship and its crew. “The President and his chief of staff exchanged whoops of joy,” wrote Newsweek at the time, “Henry Kissinger beaming ear to ear, the lot of them celebrating what seemed in that taut midnight to be a famous victory.”

By the time the announcement was translated into English and verified, however, the rescue mission was underway for the young Marines who had not completed training, much less been in combat. The only points wide enough for the American helicopters to land were the small beaches on the east and west sides of Koh Tang Island’s northern tip. When Khmer Rouge commander Em Som heard the distant thump of helicopter blades, he roused his men and sent them to their battle stations, where they locked and loaded antiaircraft guns, large machine guns, rocket propelled grenades, small arms, and waited for the Americans’ arrival in fortified bunkers.

Al Bailey (far right) on Koh Tang Island, Cambodia May 15, 1975. Photo credit: James Davis/Koh Tang Beach Club.

Nineteen-year-old Marine Al Bailey was in the first Air Force helicopter that landed on the west beach. The Khmer Rouge held their fire until the chopper was less than 100 feet off the ground, when suddenly Bailey saw the tree line light up as gunfire began to rip through the HH 53’s fuselage. Although the Marines were able to offload, the helicopter was so badly shot up that it took off and crashed a mile offshore. The second Bailey stepped onto the beach, black clad soldiers were shooting at him from less than 50 meters away. In fact, the first dead man Bailey ever saw was the Cambodian soldier he shot in the chest.

Things were not going any better on the east beach, where two helicopters had already been shot down by the Cambodians. “I shot from the distance of about 30 meters from my bunker to the helicopter,” said Em Som. “I aimed for the head and hit the tail. The helicopter was so low that we hit it, it fell to the ground without much damage.”

The Marines on the west beach were undergoing a Khmer Rouge trial-by-fire and were running out of ammunition. When a helicopter filled with reinforcements managed to land. Bailey felt an immediate sense of relief when his senior NCO, Fofo “Sergeant T” Tuitele walked down the ramp like a comic book superhero. “He stepped out of the helicopter and was like, ‘Let me get this shit under control.’ It was a walk in the park to him, he was ready to conduct business.”

The six-foot-two, 250 pound Samoan was a highly respected scout sniper who had been training these “boot” Marines on Okinawa when they were assigned this mission. Born and raised in American Samoa, Fofomaitulagi Tulifua Tuitele, better known as “Fofo,” moved to Hawaii at age 10 and joined the Marines at 18. Tuitele went to Vietnam for the first time in 1967 and during his second tour in 1968, received a bronze star and Purple Heart for saving a friend whose foot had been blown off in a battle against the North Vietnamese. Although the soft-spoken Samoan treated his men well, “nobody and I mean nobody, ever challenged him,” said Bailey. “This man had killed a rack of Vietnamese, you could see it in his demeanor and the way he carried himself.”

Tuitele first calmed the Marines on the west beach and spread them out into a defensive perimeter. He noticed an enemy machine gun position on a ridge at the north end of the beach that was raining down fire, making it impossible for helicopters to land. “I’m going to take care of this problem,” Tuitele said and disappeared into jungle. “Within 15 minutes the machine gun position was silenced,” wrote Al Bailey. “About another 20-25 minutes later, I heard more gun fire to my 11 o’clock position and then silence.”

When the Samoan emerged from the jungle, he was carrying two AK-47s, Cambodian cigarettes, and Ho Chi Minh sandals. “They’re having a garage sale on the other side of the island,” he joked. His commanding officer Dick Keith was checking their northern perimeter when he saw Tuitele carrying the AK-47s. “I asked him where he had been all morning,” wrote Keith, “to which he simply replied ‘Looking for some souvenirs, sir.’”

Fofo Tuitele with captured AK 47. Koh Tang Island, May 15, 1975. Photo: Fred Morris/Koh Tang Beach Club

When Marine Fred Morris watched Cambodian soldiers climb a huge tree overlooking their position, he pointed the tree out to Tuitele, who lifted an M60 machine gun off its stand and fired it from his hip. As he raked the palm tree with machine gun fire, men began to fall out of it. “I don’t know if they were already dead from being shot but if they were not the 70-90 feet fall had to of killed them,” wrote Morris. After things calmed down, Morris asked Tuitele if he was hurt because of the blood on his sleeve. “He just looked at his arm and said ‘it’s not mine,’ he didn’t elaborate.”

By noon, the Khmer Rouge forces were now running out of ammunition. “We couldn’t continue the fighting, because we had no bullets,” said Khmer Rouge soldier Mao Ran. “We retreated into the forest, while the Americans soldiers occupied our bunkers.” During the short break in the action, “Sergeant T” handed out AK47s, canteens, binoculars, rubber tire sandals, and Cambodian cigarettes “like he was Santa Claus.” “Most of us were 18 to 21-year-old young men, scared shitless, experiencing the throes of heavy combat for the first time. By just his presence, his calm demeanor,” wrote Bailey, “SSgt Fofo Tuitele buoyed us up past paralyzing fear.”

The Marines dug in and prepared for a long night, when they learned that that helicopters were on the way to take them off of the island. Minutes later, heroic Air Force pilots and pararescuemen (PJs) packed each helicopter with twice the normal combat load and as they took off, the perimeter shrank. When the final chopper was ready to take off, the Marines on board told the Air Force crew that a three man machine gun team (Joseph Hargrove, Gary Hall, and Danny Marshall) covering their flank was still on the beach.

It was after 8:00 p.m. when the radio aboard the AC 130 Airborne Battlefield Command and Control Center came to life. Air Force Sergeant Robert Veile suspected that it was a Khmer Rouge ruse until he asked for the Marine authentication code and the man repeated it without missing a beat. “I was the last to talk to them,” Viele told Newsweek, “I had to tell them that nobody was coming back for them.”

As the night wore on, Marines, Air Force PJs, and Seals on nearby Navy ships planned to return to Koh Tang to search for the lost machine gun team. A SEAL team led by Tom Coulter was waiting for orders to launch a search and rescue mission. Vice Admiral R.T. Coogan told him that he wanted to wait until dawn. They would drop fliers on Koh Tang announcing their intention to recover the Americans’ dead and then send Coulter and his team in unarmed and under a white flag. In an act of defiance celebrated by SEALs to this day, Coulter refused the admiral’s “suicide mission.” Marines Lester “Gunny Mack” McNemar and Captain James Davis volunteered to return to the island the next day under a white flag. When the Admiral rejected even this — his original plan — tempers boiled over. Later that night USS Henry Holt commander Robert Paterson called Coulter into his quarters for a conference call with the White House. Although he does not remember who was on the call that canceled the rescue operation, Coulter remembers that “someone on the call had an accent.”

Memorial service for the servicemen killed and left behind during the Mayaguez Incident aboard the USS Coral Sea, May 16, 1975. Photo credit: Terry Brooks/Koh Tang Beach Club

The next morning, Khmer Rouge soldiers cautiously approached the beaches on Koh Tang, unsure that the Americans had left the island. Destroyer escort USS Wilson was patrolling just off the east and west beaches, looking for any signs of the lost machine gun team. “I didn’t see the Americans withdraw, I just saw helicopters coming and going. We didn’t know if they were reinforcing or withdrawing,” recalled Mao Ran. Once they were positive the Americans were gone, the Khmer Rouge soldiers walked the beach and were amazed by the equipment left behind: “We saw they had everything, including a tool for swimming and food. Some even had two guns,” he said. “We picked them up. At the helicopter crash site there were pistols and many other things that were left behind. The walkie talkie was still operating: ‘pip, pip.’”

Mao Ran also saw the bodies of dead Americans: “I didn’t count how many there were, but I remember dragging five or six bodies myself [to the water]. If we’d known the Americans would have come back some day to look for the bodies, we would have put all the bodies in one easy-to-find place.” Instead they tied the bodies to a row boat and towed them “deep into the sea…”

A few days later, a Cambodian soldier was carrying wooden poles near the water well when he saw a man lurking in the jungle. “Who are you?” he asked with irritation, “Why don’t you help me carry the wooden poles and are just trying to run away?” When the mysterious man ran for his life, the soldier put down his load, squatted next to the well to draw water, and noticed strange boot prints. “‘Brother, I saw someone drinking water and he went running into the forest when I called out at him,’” the soldier told Mao Ran. “The footprints didn’t belong to our men. It was the footprints belonging to the boots of the American soldiers.” The Khmer Rouge assembled a search party.

Although there are different accounts of who killed him and how he died, there is a firm consensus that by the end of the day, one of the Marines, probably Joseph Hargrove, was dead.

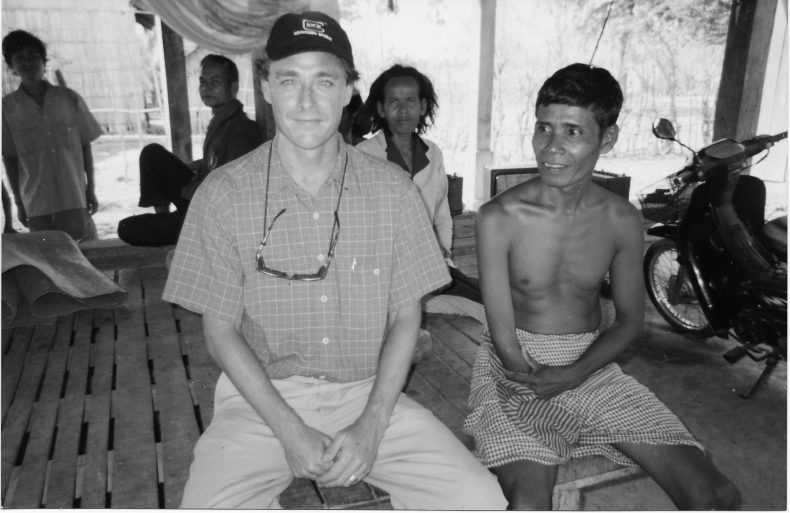

Peter Maguire with Mao Ran, a Khmer Rouge veteran of the Mayaguez Incident. Photo courtesy of Peter Maguire.

The Cambodian soldiers realized that each night someone was stealing the rice and fish from their cooking pot. “Our men complained, ‘We don’t know who has eaten the old rice,’” said Em Som, “but they didn’t know that the Americans had stolen their rice. The rice was missing every day.” After they found more boot prints on the trail to the kitchen, after the sun went down four Khmer Rouge soldiers hid on each side of the trail. At about 10 p.m. two Marines crept down the trail until armed men emerged from the bush and surrounded them. The Americans raised their hands and used the body language and drew pictures in the dirt to explain that they had been left behind. “We cooked rice in the night and let them eat,” said Em Som. “Now that they were in somebody’s hands they were worried. It would be the same for us.” The Khmer Rouge commander did not consider the exhausted abandoned soldiers a threat and did not even bother to tie them up.

The Cambodian soldiers on Koh Tang had no contact with their leaders because their radio had been destroyed. When a boat finally reached the island, Em Som informed Khmer Rouge naval commander Meas Muth of the captured Americans and was ordered to take the prisoners to the port of Kompong Som. Once they reached the port, the two Americans were put in a car and taken “to Mr. Meas Samouth’s [Meas Muth] place.”

“We saw the Americans die with our own eyes, but it was not my men who killed them,” said Em Som. “They were not shot. They were killed with a stick.”

Once Meas Muth was named as a war crimes suspect and charged (in absentia) by the UN’s Khmer Rouge war crimes court, Em Som and other Khmer Rouge soldiers from the Mayaguez Incident began to change their stories. However, today there is firm consensus among the leading Khmer Rouge researchers that the Ford administration left three living Marines behind on Koh Tang Island on May 15, 1975. No less of an authority than Rich Arant, a former U.S. Air Force human intelligence officer, Defense Intelligence Agency field investigator in Cambodia, and translator for the UN’s Khmer Rouge Tribunal believes that Marines were left behind: “Multiple first-hand witnesses from the Khmer Rouge 164th Naval Division have given detailed sworn testimony regarding the capture of U.S. military personnel on Tang Island, events surrounding their handling on the island and the Cambodian mainland by the Khmer Rouge chain of command, and their final disposition.”

“Based on the extensive evidence I have seen about the Mayaguez affair,” wrote Craig Etcheson, the dean of Khmer Rouge war crimes investigators, who has been conducting field research in Cambodia since the early 1990s and was the lead investigator for the UN’s court, “I am convinced that several U.S. Marines were captured alive on Koh Tang and later executed by the Khmer Rouge.”

Forty-three years after the Mayaguez Incident there is a renewed effort to get long overdue recognition for the veterans of the last battle of the Vietnam War. While the Marine, Air Force, and Navy officers were heavily decorated for the disastrous rescue mission, the unsung heroes, the enlisted Marines who prevented a much worse outcome, have not received the acknowledgement they deserve. Why were these veterans denied the Vietnam Service medal in 2016?

Only recently has the valor of Marine Fofo Tuitlele come to light. “Many more lives would have been lost for not the actions of SSgt Tuitele,” wrote Al Bailey. “His talent and experience were needed on that fateful day.” The effort to get the Samoan the recognition he deserves has been spearheaded by the enlisted Marines whose lives he saved. “I can tell you that what SSgt T directed us to do and how he re-supplied us did two things for me and I’m sure the others,” wrote Herrera. “We had a little more confidence and supplies to continue the fight. Without that I do not know if we would have survived.”

In May, American Samoan Congresswoman Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen filed a DD-149 “Application for Correction of Military Record” and four letters from Marine eyewitnesses on Koh Tang Island. Al Bailey put it best, “Whatever courage I displayed that day, I drew from that courageous man.”

Prof. Peter Maguire is the founder and director of Fainting Robin Foundation and the author of Law and War: American History and International Law, Facing Death in Cambodia, and Thai Stick: Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade. He has taught the law and theory of war at Columbia University, Bard College, and the University of North Carolina Wilmington