Taiwan’s DPP administration led by Tsai Ing-wen has just reached its halfway point. It now awaits the voters’ first judgment in the November local elections.

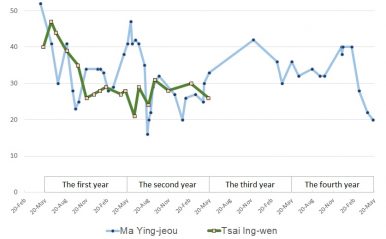

A notable feature of the Tsai administration has been its poor approval rating in opinion polls. Exactly why Tsai’s approval rating has been persistently low is something of a puzzle. She has, after all, introduced numerous reformist measures that previous administrations did not dare take, and the Taiwanese economy has remained stable. In fact, it looks as though Tsai’s path in opinion polls is following that of her immediate predecessor, Ma Ying-jeou (see figure).

Figure: Comparison of rates of satisfaction with Ma and Tsai

Source: Author, based on opinion polls conducted by TVBS

The next presidential election, which is scheduled in January 2020, takes place just 14 months after the local elections. That leaves the loser this year with very little time to reorganize its party machine and reverse its fate – the equivalent of trying to achieve a comeback victory in a game of football after being down 2-0 at the end of the first half. Perhaps it is better, then, to think of the elections this November as the end of the first half, rather than as midterm elections.

In November, Taiwanese voters will be electing mayors and governors, councilors, village and community chiefs, and other local officials. Most of the media’s attention is focused on the mayoral and gubernatorial elections. There are 22 cities and counties in Taiwan; among them six metropolitan cities account for 69 percent of the population.

A peculiarity of Taiwanese politics is that China-Taiwan relations are not an issue in local elections, yet the election results could well influence cross-strait relations. A DPP loss would be interpreted as a rejection of the Tsai administration’s China policy by Taiwanese voters, and there would be mounting pressure on the Tsai administration to change course on China. If the DPP wins this election, by contrast, it would be seen as an endorsement of Tsai’s China policy. Their local nature notwithstanding, the November elections clearly have a broader significance.

Theoretically, as long as the DPP keeps four metropolitan cities and the KMT keeps only one (New Taipei City), the DPP will retain its edge for the coming presidential election. However, if the KMT is able to capture three or four small counties – as it seems likely to do – it would see the KMT winning more cities and counties than the DPP manages, and the Taiwanese media would report this as a KMT victory and a DPP defeat.

There are many factors during the election campaign that may influence voters’ choices, and they will need to be watched closely. For now, let’s look at two. The first, as already noted, is the president’s low approval rating. How this will or will not manifest in the choices made by voters in a local context remains as yet uncertain.

The second factor is the issue of power supply this summer. The Tsai administration is determined to move Taiwan from nuclear power to green energy, but now is a transitional period, and for maximum supply the government will have to rely on several very old thermal power stations that are susceptible to breakdown. This is something of a tightrope for the government. Should a large-scale power outage occur, forcing people to spend a day without air conditioning in Taiwan’s sweltering summer as happened in August last year, the DPP could face some angry voters in November.

Even though Tsai would still have a good chance of being reelected, an ambiguous outcome from the local elections would cast a shadow over her administration and give Beijing more room to intervene in Taiwan’s domestic politics. The uneasy, troublesome situation in Taiwan would continue.

It has been nearly six years since Xi Jinping became leader of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi’s policy toward Taiwan is usually summarized as a strategy involving both the carrot and the stick. On the one hand, to curb the Taiwanese independence movement, Xi has shown himself more than willing to deploy Chinese hard power, including diplomatic and military pressure. Meanwhile, to promote unification with Taiwan, Xi has mobilized China’s soft power, offering the Taiwanese people the chance to participate in “the Chinese Dream” and earn “China money.”

This two-pronged strategy has intensified since 2016, when Beijing suspended all talks between Taiwan and China. Taiwan’s scope to participate in the international community has steadily narrowed, it has lost diplomatic ties with four countries, PLA aircraft flying around Taiwan have become a daily occurrence, and a military drill involving an aircraft carrier was even held for the first time off Taiwan’s eastern coast.

In the next two years, the political situation across the Taiwan Strait will be shaped by Taiwan’s 2020 presidential election. Yet it is unlikely that Xi Jinping will modify his stance. Nor is there much chance that Tsai Ing-wen will change course. The most likely outcome is a continuation of the current stalemate.

For Beijing, the continuation of a DPP administration is unacceptable, and it will do what it can to hamper its chances, even though it knows that the probability of Tsai’s reelection is still high. Xi will step up efforts to contain Taiwan before the election to demonstrate China’s overwhelming power to Taiwanese voters. This has the potential to produce turbulence, and even to a Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis.

Recognizing this, Taiwan, Japan and the United States will need to closely monitor the situation, exchange views, share analyses, and prepare for tensions.

Yoshiyuki OGASAWARA is an Associate Professor at the Graduate School of Global Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.