With discussion at the recently concluded Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore heavily focused on the Korean summit and the U.S./China spat over the South China Sea, it would be easy to forget about China’s pursuit of the “commanding heights” of all strategic competition: outer space and cyberspace. However, while there can be no doubting China’s ambition in this area, one can make the argument that the country is, at present, far from those heights.

China’s leaders state clearly that the country is aiming to reach the highest ground possible of economic and military power. To do so, it knows the foundations of its cyber defenses will have to be strong. To that end, China is investing heavily in frontier technologies, such as quantum computing and artificial intelligence. As President Xi Jinping has said, there can be no national security without cybersecurity.China is also making tremendous strides in operational cyber technologies for public security, such as facial recognition, vehicle and smart-phone tracking and citizen surveillance. This is against the background of substantial reforms in public security intelligence, persuasively analyzed by Edward Schwark recently in the China Journal.

But the foundations of its cyber defenses, including in the Ministry of Public Security, remain weak. This is the testimony of numerous Chinese sources.

Taking universities as the foundation of all formal cybersecurity education and research in China—as the government does—the country is not well served. The Chinese University Alumni Association ranks no university in the country as world class in this field. Most cybersecurity departments operate inside computer science or engineering faculties and suffer accordingly. There has been little development inside China regarding the study and teaching of non-technical aspects of the problem: such as psychology (insider threats), management, business or economics.

The government moved to correct this in 2016 by elevating the subject to a “Level One” discipline at the university level, but such reforms usually take decades to have the desired effect. It is hard to imagine a workforce solution to China’s manpower deficit in this field, projected to be 1.4 million by 2020. We should also note that this estimate, like similar efforts in other countries, is probably only addressing technical specialists, not cybersecurity work roles in management or social spheres.

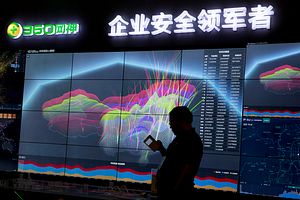

Overall, China’s cybersecurity industrial complex is a work in progress. Two state-owned defense electronics companies, CEC and CETC—both Fortune 500—are the industry leaders, operating through their two main subsidiaries, ChinaSoft and China Cybersecurity. They are complemented by more than 400 privately-owned cybersecurity firms in China, many of which are thriving off the back of rapidly rising demand for products and services. Among the leaders in this group is Qihoo 360.

The private sector growth in this field, however, is from a low base, with its total turnover in 2014 for the entire country being smaller than that of the global privately-owned leader, Symantec, in the same year (6.5 billion USD). That year, the top 20 Chinese private sector firms accounted for 25 percent of the sector’s turnover inside the country.

In this environment, despite a robust push for indigenization of this sector beginning in 2014, foreign firms remain not just important but absolutely essential to the protection of cyberspace in China.

At the operational level, the cybersecurity of most Chinese government agencies and corporations remains weak to very weak. The biggest surprise in this regard is in the Ministry of Public Security, according to open source reporting inside China. Another surprise is a Chinese private sector analysis from 2017 which ranked government cybersecurity in Lhasa (Tibet) and Urumqi (Xinjiang) amongst the lowest in the country, in spite of the political sensitivity of these two locations from an internal security point of view.

China’s Great Firewall, in practice as well as in conception, may be as weak as its namesake, the Great Wall, not least because of the efforts of Chinese émigré geeks and their Western colleagues intent on undermining it. These moves started more than a decade ago. For example, scholars in Cambridge University in 2006, working with an unnamed Chinese national, demonstrated a method to convert official blocking by key word on the part of Chinese censors into a limited denial of service attack on the Great Firewall itself. In addition, according to information from 2017, organizations like the U.S. based Broadcasting Board of Governors, actively devise circumvention technologies that they say liberate billions of web site sessions from the efforts of authoritarian governments like China to block them from its own citizens. Of course, the Chinese government moves aggressively to defeat circumvention technologies, but that industry is alive and well outside China and is committed to undermining the country’s censorship. Analysts, such as Ralph Jennings writing several months ago in Forbes magazine, report continuing use domestically of circumvention technology in China in spite of what he called the “whack-a-mole” policy of the government, implying a mixed picture of success and failure for it.

Dr. Greg Austin is a Professorial Fellow at the EastWest Institute, with a 30-year career in international affairs, including senior posts in academia and government. His latest book, Cybersecurity in China: The Next Wave was published this Spring. This article has previously been published on the EastWest Institute Policy Innovation Blog.