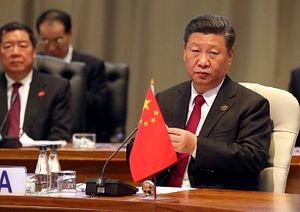

Xi Jinping has a global vision for China and has centralized foreign policy around himself and the CCP. In this six-part blog series, MERICS researchers take a closer look at the (new) setup of China’s foreign policy leadership, institutions, budget, and personnel – as well as on its policy approach to Europe. This is part 1.

Xi Jinping has put the world on notice that China intends to be an active global player. In support of this new and more visible profile, the Chinese leadership has changed the foreign policy setup to give Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) greater control. This was reflected in changes to the foreign policy leadership team at the CCP’s National Congress in November 2017 and the National People’s Congress session in March 2018.

As more details become known, it is time to take stock of this reorientation. This blog series will focus on concrete changes to China’s foreign policy leadership team, institutional structures, budgetary practices and personnel policies as well as of adjustments of its policy approach to Europe.

Foreign Policy Tailored to Fit Xi Jinping

After assuming the leadership of the Party in 2012 and of the state in 2013, Xi left no doubt that he saw the shifting global environment and the relative decline of U.S. power as a strategic window for China to increase its global influence. The Chinese president began talking about a “new type of international relations” in 2013. He coined new concepts such as the “community of a shared destiny for humankind,” and his administration even managed to insert this language into several UN documents. And he launched the Belt and Road Initiative with great fanfare.

A lot of these concepts remain vague, but it is fair to assume that China sees itself at the center of this new type of international relations. This became clear at the high-level Central Conference on Work relating to Foreign Affairs on June 22 and 23, 2018. In a break from previous speeches, Xi no longer mentioned “nonalignment” with or “noninterference” in other countries. Instead of “working toward” he now wants to “lead” the reform of global governance.

The vision of China’s central role in the world is matched by Xi’s central role in foreign policymaking. Several so-called leading small groups were established to strengthen Xi personally, and the CCP more broadly, to take charge of foreign policymaking at the expense of the Foreign Ministry. The work conference in June was the second under Xi’s leadership, while his predecessors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao had only held one each. In a visible break from past practice, state media reports about the conference fail to mention previous leaders and their concepts or even the party leadership, but are full of references to foreign policy projects and concepts developed under Xi.

Personnel Appointments Are Closely Linked to Xi

The personnel appointments to top foreign policy-making positions are all closely linked with Xi or his concepts. Party factions around Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin are marginalized and those in the driver’s seat are much closer to Xi personally or had a role in shaping or promoting his major concepts and initiatives, from the “Belt and Road” to the “China Dream.”

The new Politburo Standing Committee members Wang Huning and Wang Yang, as well as the new Politburo member Yang Jiechi, had been deputy leaders of the BRI “leading group” since 2014. The new Vice President Wang Qishan is a personal friend of Xi’s, and the heads of the CCP International Liaison and United Front Work departments, Song Tao and You Qian, have likely connections to Xi through their careers in Fujian where Xi served as governor. Wang Huning is known as a chief theorist and as the top aide supposedly behind the “China Dream” concept.

The announced “upgrade” of the former Central Leading Small Group on Foreign Affairs to Central Foreign Affairs Commission can be interpreted as a signal of increased party control over foreign policy making (see part 2 of this series). The commission has a coordinating role between state institutions, but is also tasked with strengthening the CCP’s role, and its general office will likely be equipped with more staff and authority than that of the previous Leading Small Group.

The establishment of the China International Development Cooperation Agency points to more centralized control in an area two state institutions previously competed over: the ministries of commerce and foreign affairs (see part 3 of this series). Wang Xiaotiao, who heads the new institution, promoted the BRI as deputy director of the powerful National Development and Reform Commission, and in his new role makes the BRI central to every statement. His appointment may indicate a shift from Chinese development cooperation being driven by short-term commercial benefit to subordination to longer-term strategic interests.

The increased focus on developing a more effective, forward-leaning foreign policy is supported by further strong increases in the foreign affairs budget and efforts to strengthen the diplomatic corps (see part 4 and part 5 of this series). Expenditures remain on a steady upward trajectory and show an increasing strategic focus on China’s contributions to multilateral institutions and security-related activities such as peacekeeping and conflict-resolution diplomacy.

The Chinese government appears to put more emphasis on diplomatic support for China’s longer-term goals. Beijing has left several seasoned ambassadors at high priority embassies such as Moscow or London in their posts for up to nine years. Newly appointed ambassadors on average have more regional experience than their predecessor generation.

Ambassadors to European capitals also command greater regional expertise, which is supposed to help them orchestrate Beijing’s onoging charm offensive toward Europe. But while China appears as a sensible partner in times of a fraying transatlantic relationship in some areas, Beijing’s expanding foreign policy reach increasingly puts Europe and European unity to the test (to be discussed in part 6 of this series).

Europe – as well as other major players in world politics – is well advised to closely monitor China’s new foreign policy setup and the outputs it produces.

Thomas Eder is a research associate at the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) in Berlin, Germany.