Since Xi Jinping came to power, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) has taken a significantly hardline turn. Xi has repeatedly instructed MoFA officials to demonstrate “fighting spirit (斗争精神).” As a result, MoFA adopted a set of strategies that have been described as “wolf-warrior diplomacy.” Under this strategy, MoFA officials see the world through a lens of struggle with the West, especially the United States, in international discourse and other arenas, as MoFA spokesperson Hua Chunying declared in an internal meeting. The duty of Chinese diplomats is to rebut “foreign attacks” and spread Chinese talking points.

Therefore, the world has seen increasing aggressiveness from MoFA officials, from promoting lies about the origins of COVID-19 to physically attacking protesters in Manchester. The excessive hostility of MoFA officials significantly damaged China’s international image. Hopes for modifying “wolf-warrior diplomacy” after the November 2022 meeting between Xi and U.S. President Joe Biden were shattered by China’s reaction over the “spy balloon” incident, Wang Yi’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, and China’s polemics against the United States.

However, one cannot understand China’s diplomacy fully by only looking at MoFA. Since Mao Zedong, Chinese leaders have approached foreign affairs in several dimensions. In addition to state-to-state relations, China established relations with foreign political parties, localities, individual politicians, business leaders, and other significant members of the society. Furthermore, China cultivates foreign individuals, the so-called “old friends of the Chinese people.”

During the Mao era, China adopted this multidimensional diplomacy to break out of diplomatic isolation. For example, Mao repeatedly met with leaders of the Japanese Socialist Party to establish an unofficial relationship with Japan. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) also established ties with pro-trade Diet members and business leaders, which led to the flourishing Sino-Japanese trade. In addition, Mao sent key diplomatic intentions during meetings with foreign “friends.” When Mao met with Edgar Snow in 1970, he signaled his intention to improve China-U.S. relations by inviting President Richard Nixon to visit China and meet with him directly.

China-Japan Relations: A Case Study in Multidimensional Diplomacy

The case of Sino-Japan relations provides an interesting case study. On the one hand, historical issues, maritime disputes, and great power competition in Asia deteriorated bilateral relations. On the other hand, both Beijing and Tokyo understand the importance of engagement in strengthening economic ties and maintaining regional peace. As a result, Japan and China developed multiple layers of official and unofficial diplomatic channels to maintain communication.

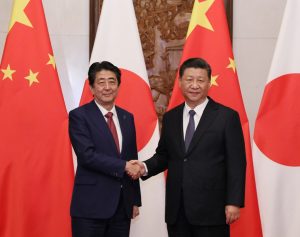

Sino-Japanese relations dropped to the freezing point after the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Island disputes between 2010 and 2012 and then-Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine in 2013. However, the uncertainty over Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. 2016 presidential election drove Beijing and Tokyo toward a reconciliation. Abe’s visit to China in 2018 illustrated the vitality of multidimensional diplomacy in China’s foreign policy.

Longtime U.S. China hand Chas Freeman has highlighted the importance of cultural exchange as “an instrument for the subversion of dogmatism,” which soften the hostility in a foreign society and disincentivizes the foreign government to conduct adversarial behaviors. In the case of China, cultural exchange organizations are backed by MoFA. Thus, they play critical roles in signaling China’s diplomatic intentions and paving the path ahead of formal diplomatic negotiation.

The Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) is a MoFA-affiliated, semi-official cultural exchange organization. Its duty is to advance Chinese diplomatic goals by establishing connections with foreign subnational actors, such as businesses, cultural groups, think tanks, academic institutions, and local governments. In addition, the CPAFFC leads seven regional-focused and 29 country-specific friendship associations.

For example, the Sino-Japan Friendship Association (SJFA), currently headed by former Chinese Foreign Minister and renowned Japan hand Tang Jiaxuan, is historically active in shaping Sino-Japan relations. It has built an extensive network in Japanese politics, including different political parties, local governments, and social groups. Since its foundation, it has facilitated some of the most important Sino-Japan negotiations, such as Japan’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China in 1972 and the 1978 Sino-Japan Treaty of Peace and Friendship.

Continuing that trend, the Sino-Japan negotiations on detente started with a series of CPAFFC meetings almost one year before Abe’s Beijing visit. Between December 2017 and January 2018, the CPAFFC and SJFA hosted five meetings with Japanese counterparts, including Japanese Ambassador to China Yokoi Yutaka, President of All Nippon Airway (ANA) Ito Shinichiro, Japanese painter Kinutani Koji, and other political and business leaders. The Chinese representatives declared 2018 a “window of opportunity” for improving bilateral relations since it marked the 40th anniversary of the signing of the 1978 Sino-Japan Treaty of Peace and Friendship. Thus, both sides should “seize the opportunity” to enhance economic, cultural, local governance, and youth exchange collaborations. China also invited Japan to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

In general, China used these meetings to signify its readiness to negotiate with Japan and address mutual concerns in trade and other areas. The 20th and 30th anniversaries of the Sino-Japan Treaty resulted in state visits and the signing of major China-Japan joint statements. Thus, China highlighted the 40th anniversary to show its sincerity for a major diplomatic breakthrough; Beijing wanted to seize the opportunity to thaw the bilateral relations. China pulled the BRI card to discern Japan’s sincerity by testing whether Tokyo wanted to cooperate with Beijing’s concerns.

These preliminary negotiations produced fruitful results; official diplomatic talks reflected the spirits of these negotiations. On January 28, Abe sent Foreign Minister Kono Taro to visit Beijing. While meeting with Kono, Premier Li Keqiang said that Sino-Japanese relations were “heading toward positivity despite uncertainties.” This rhetoric departed from the mutual hostility during the deep freeze. In addition, Li invoked the 40th anniversary theme and declared that 2018 should be “the year of opportunity to put Sino-Japanese relations back to the normal track.” Kono welcomed Li’s declaration and claimed that Japan was ready to cooperate with China to manage the Senkaku Island disputes and participate in the BRI. He also invited Li to visit Tokyo for the China-Japan-Korea summit in May 2018.

The Kono visit started a series of high-level meetings between China and Japan, such as Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Tokyo in April, Li Keqiang’s visit to Tokyo in May, the Abe-Xi meeting in Vladivostok in September, and Abe’s visit to Beijing in October. Besides these formal state visits, China cultivated key individuals to support the Sino-Japan détente. One such individual was LDP Secretary-General Nikai Toshihiro, whom Xi Jinping considered “an old friend of the Chinese people.” He met with Xi and led a 700-member business delegation to Dalian and Chengdu. In addition, Wang Yi met with Nikai individually after meeting with Abe in April, showing that China viewed him highly. China wants to use Nikai’s position and influence in the LDP to strengthen political support for Sino-Japan reconciliation.

Another critical individual was Yamaguchi Natsuo, the head of LDP coalition partner Komeito, who visited Beijing twice during the summer of 2018 to coordinate Abe’s state visit. On August 20, Yamaguchi met with Song Tao, the director of the International Liaison Department, which manages CCP’s relations with foreign political parties. On September 5, Yamaguchi met with Wang Yang, the chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, who oversaw the “United Front” work in the CCP. Both parties recalled the long CCP-Komeito friendship and Komeito’s vital role in Sino-Japan relations and agreed to strengthen the CCP-Komeito ties. Yamaguchi delivered Abe’s letter to Xi and conveyed Abe’s hope to deepen high-level communication and meet with Xi personally. He also claimed that Komeito would play a vital role in constructing a close Sino-Japan partnership.

The Chinese leadership holds a positive view of Yamaguchi. Between 2013 and 2017, Yamaguchi visited China three times, and the visits in 2013 and 2015 followed significant Sino-Japanese diplomatic crises: Japan’s nationalization of the Senkaku Islands and the adoption of security reform legislation in 2015. Thus, both Chinese and Japanese leaders saw Yamaguchi as a valuable and trusted communication channel between Beijing and Tokyo. In addition, the CCP views Komeito as a “friendly force” in Japan. Komeito adopted a policy of recognizing and engaging the People’s Republic of China since its foundation in 1964 and has a peace-oriented foreign policy agenda. By strengthening ties with Komeito, the LDP’s ruling partner, the CCP hoped that Komeito could “soften up” Abe’s security policy.

Abe’s Beijing visit produced fruitful results. China promised to liberalize access to its domestic market for Japanese investors. Both countries also agreed to deepen economic cooperation in currency swaps, innovation, industrial development, and financial market integration. Besides the economic relationship, Beijing and Tokyo initiated negotiations on a mechanism to prevent air and maritime accidents and pursue maritime search and rescue. China even agreed to send new pandas to Japan. The visit also became Abe’s defining legacy with China. When Abe was assassinated last summer, Xi Jinping declared that the former prime minister “made contributions to improving Sino-Japan relations.”

Abe’s 2018 visit shows that Chinese diplomacy is not as dogmatic as observers declared. Beijing’s willingness to interact with an archrival (Japan) and a “troublesome” leader (Abe) illustrates diplomatic flexibility that even the United States cannot match. In addition, when Beijing is ready for negotiation, it will first use low-level channels to test the water.

These are valuable takeaways for Washington when engaging China. First, communication with China should never die; Abe demonstrated that engagements could shape China’s behavior. Second, Washington should not dismiss lower-level and Track II diplomacy efforts. They will serve as critical information and communication channels. The United States can use these channels to discern China’s intentions, cultivate key actors within the Chinese government, and shape China’s foreign policy choices.