There has been no shortage of references recently to the fact that China and Nepal are about to conduct a second round of joint military exercises, titled Sagarmatha, in Chengdu in Sichuan, China, next month. The two countries held their first joint military exercise, Sagarmatha Friendship 2017, for 10 days in Kathmandu in April last year.

Often neglected in a focus on headlines alone is the fact that it has been reported that there will be no more than 15 personnel taking part in this edition of the exercise. Nonetheless, even as the scale and sophistication of the China-Nepal joint military exercise is nowhere comparable to the kind that India holds with Nepal, it still raises hackles in New Delhi.

India does the Surya Kiran series of military exercise with Nepal twice a year, alternating between India and Nepal. The last one, SURYA KIRAN-XIII, was held in June this year. Reportedly, this series of military exercise with Nepal remains the “largest military exercise in terms of troop participation” that the Indian army undertakes with any other country. A press statement noted that that the focus of the exercise was on counterterrorism operations.

While India can find some solace in the depth of New Delhi’s relations with Nepal, India’s concerns nonetheless have been growing about this new facet of the China-Nepal relationship that has seen an uptick, particularly in recent years.

That concern is not entirely without reason. India’s own relations with Nepal have seen some testing times. More generally, Beijing’s proactive diplomacy in South Asia and the Indian Ocean remains particularly sensitive to New Delhi. While these are not new manifestations to be sure, China’s outreach has indeed picked up the pace in recent years.

The growing security ties between China and Nepal also comes in the wake of growing commercial and economic linkages as well. China pumped in more than $8 billion in investments in Nepal last year and overtook India as the biggest foreign investor three years ago. That is no small feat.

To be sure, it has not all been smooth sailing for China. For example, Nepal recently cancelled two massive hydroelectric projects that Chinese firms were contracted to build. Furthermore, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been stepping up his outreach to Nepal as well, making his third visit to Kathmandu in just four years.

But, for perspective, Modi’s latest visit was also to repair the damage done by the two-month long Indian economic blockade of Nepal in 2015, a move that had caused serious hardships for ordinary Nepalis. Everything from fuel to medicines and earthquake relief supplies were affected, resulting in a huge backlash against India in Nepal. This had happened in the backdrop of Nepal’s efforts to amend its Constitution and India’s efforts at championing the case of the Madhesi people, which made India a villain in the eyes of ordinary Nepalis. Following these events, Nepal’s outreach to China grew even as the Himalayan Kingdom attempts to maintain a balance in its relationship with these two giants on its border.

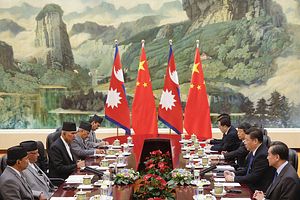

That balance appears set to continue. For example, former Prime Minister of Nepal and alliance partner of the Oli Government, P K Dahal Prachanda, is slated to visit India next month from September 7 to 12, a few days before he travels to China. Prime Minister Oli too had done this balancing act earlier this year, when he travelled to India first before he headed to Beijing.

All of this indicates that the Oli government is possibly just keeping its options open, and that there are really no major or dramatic changes to Nepal’s foreign policy in spite of individual moves that might be taken.

Yet India’s fears about China’s encirclement in the neighborhood are not without any basis. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s aggressive strategic pitch through his Belt and Road Initiative and debt trap diplomacy have seen the strengthening of China’s footprint in the Indian neighborhood.

The case of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is the oft-cited case in point. But the Maldivian government’s approach toward India is another instance of how the traditionally pro-India Maldives has turned against New Delhi, with support from China.

To be sure, India must shoulder its own share of blame for not managing these relations well. But the fact also is that for the smaller countries in the region, the economic incentives offered by China has been critical. Nepal’s decision to join the BRI will beef up Beijing’s role and presence in Kathmandu manifold. Similarly, Modi’s efforts to stem China’s influence in Nepal would depend on India’s ability to deliver on the promises made during Oli’s visit to India earlier this year, apart from any wider geopolitical calculations or moves.

It is worth keeping in mind that the fact that India and China are competing on similar projects including infrastructure development means this competition is likely to be lopsided. India does not enjoy a good track record in completing such ventures on time. The India-Myanmar-Thailand trilateral way is a case in point, with the project, initially conceptualized in 2002, seeing many delays and the latest update suggests 2021 as the completion date.

Certainly, in an election year, Modi will want to show clear successes in his neighborhood-first approach. But unless India strengthens its delivery capacity, New Delhi is bound to continue to lose to China. Ultimately, irrespective of what India’s neighbors do with China in the economic or military domains, New Delhi’s surest bet to shore up ties with these countries is to focus on shoring up its own reputation as a provider of security and prosperity. Nepal is no exception to this rule.