Last week, reports surfaced that Cambodia and Laos had forged some sort of consensus to manage longstanding border issues. While both sides have long sought such mechanisms following previous rounds of tensions, the so-called consensus deserves close scrutiny given the opportunities and challenges it presents for the two countries.

As I have noted before in these pages, Laos and Cambodia, two neighboring Southeast Asian states, share a 540-kilometer, partly demarcated land border, which has been a source of occasional disputes and differences. In 2016, simmering border tensions yet again threatened to boil over into potential conflict and the situation was only de-escalated following intervention by the leaderships of both sides.

The two countries have nonetheless continued to hold exchanges to better manage their border issues. This includes not only managing potential escalation and differences over border surveys and demarcation, which has still proved contentious, but also making inroads in areas of common interest, be it in tackling cross-border crimes such as drug trafficking or making progress in aspects such as legal border crossings and facilitating communication between border facilities.

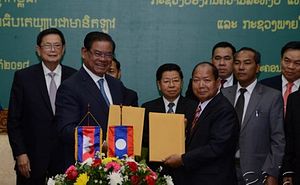

Last week, reports surfaced that Cambodia and Laos had forged a consensus of sorts to manage tensions along the border. Media reports suggested that the two countries had agreed to de-escalate border tensions in Stung Treng province during a World Economic Forum (WEF) meeting that was held in Hanoi, Vietnam.

On September 14, Cambodian media outlet Khmer Times quoted Kao Kim Hourn, the minister attached to the prime minister’s office, as saying that the two governments had agreed on a “three-point resolution” to manage border tensions, with the first and second points related to both sides withdrawing all their troops from disputed areas, and the third on the holding of joint patrols, either with ground personnel or drones, with the aim to combat criminal activities along the border. He added that the Cambodian military had been ordered to withdraw from the disputed Ou Ta Ngav area, and that a joint border committee would periodically review any future issues that arise.

That such a consensus has been reached comes as little surprise. As mentioned before, the flaring up of tensions back in 2016 reinforced the importance of at least better managing some of these border issues for leaderships on both sides, even if actually reaching some sort of temporary resolution had proven challenging. And with Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and his ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) having successfully secured another term in power following general elections in July, there has since been a greater focus on stabilizing ties with the country’s neighbors and major partners.

The exact contours of this consensus remain rather vague for now. For instance, is unclear exactly what the role of the joint border committee will be within the context of other mechanisms that the two sides already have on the defense side, including annual meetings already held by ministries, or how these joint patrols would fit into existing areas of collaboration the both countries have set up thus far as well as what areas they will cover.

Such specifics will be important in assessing the effectiveness of such a consensus as well as its sustainability. Given the sensitivity of these border issues as well as the difficulty of resolving or even managing them in the past, those questions cannot be overlooked even amid the sunny optimism that might be emanating from both sides following the recent consensus forged.