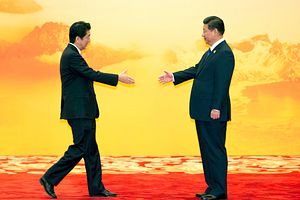

Half a decade has passed since Xi Jinping’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was first unveiled in Kazakhstan. Nevertheless Japan continues to flip-flop on the audacious vision.

On the one hand, Tokyo has been ramping up its diplomatic détente with China. Since mid-2017, positive signs of potential cooperation have been rising along with a series of reciprocal high-level official visits to discuss a whole range of issues, including but not limited to collaboration over infrastructure development. In tandem with its rising tension with United States, China has also largely welcomed Japan’s embrace. Taking cooperation a step further, in an iteration of the Japan-China High Level Economic Dialogue, both sides pledged to constructively establish a “Sino-Japanese public-private sector committee” to fuel intensified efforts to improve infrastructure in third countries. Southeast Asia will become the most visible test ground of the Public Private Partnership (PPP).

However, while promoting his concept of “Asia’s Dream” (presumably a counter to Xi’s “Chinese dream”), Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has frequently spelled out various conditions for Japan to participate in BRI projects, such as good governance, transparency, and fairness. There are lingering fears in Japan that Chinese projects might potentially hurt the debtor nation’s finances. Furthermore, Tokyo has been pioneering its own “belt and road,” ramping up its signature Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI) and subsequently incorporated similar thinking into the newly established Indo-Pacific Fund with Australia and the United States so as to meet global appetites for infrastructure investment.

On the domestic level, these flip-flops are understandably aimed to preempt political dissent among various factions. From a geopolitical standpoint, such an approach ostensibly enables Japan to kill two birds with one stone – countering China’s influence and maintaining U.S. resilience. However, the overpoliticization and overwhelmingly geopolitical representation of China’s BRI vs. Japan’s PQI might miss the point.

Southeast Asia’s Infrastructure Gap: A Growing Appetite For Burden-Sharing

Dotted around Southeast Asian cities these days are Chinese construction landmarks, tangible symbols of China’s growing influence in the region. Once Xi jumpstarted the “going out” policy, the regional infrastructure market was quickly engulfed by a Chinese “invisible hand,” which worked astutely to secure numerous infrastructure deals across the region. Unlike Japan’s customary cautious decisiveness toward large-scale infrastructure projects, Chinese “patient capital” has a higher tolerance for long-term risks.

China’s enduring desire to develop massive infrastructure projects has been the cause of euphoria among host governments. The thriving “politics of development” trend among Asian leaders has besotted them with the belief that rapid infrastructure development will drive economic growth and social equality, and concomitantly provide a veneer of political legitimacy. The drawback is that local governments, obsessed by the intriguing incentives, have been somewhat foolhardy about taking on infrastructure projects. As a result, many have foregone reliable feasibility studies, prompted short-term construction booms, and, been eventually dragged into Chinese patient capital’s “play it by ear” approach toward various externalities.

In Malaysia, the staggering scale of China infrastructure projects, coupled with corruption and fears of “debt-trap diplomacy,” has been criticized by newly elected Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamed as the revival of Chinese neocolonialism. Former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s political downfall raised doubts on the sustainability of the BRI as well as creating a new “compensation” trap if the incumbent government axes infrastructure deals.

Meanwhile, the $6 billion Sino-Laos rail project has exacerbated the precarious debt levels of Laos, which already amounted to 68 percent of GPD in 2016. As Laos was not able to contribute 40 percent of start-up capital in cash as per the joint venture’s requirement, its government borrowed $465 million — tantamount to 5 percent of Laos GDP — from China’s Export-Import Bank (Exim). In Myanmar,, the suspended Myitsone Dam — previously approved by the military junta in cahoots with the notorious domestic conglomerate, Asia World — leaves the new government in a bind. Myanmar has chosen to compensate for the suspension by granting further concessions to China in the $7.5 billion Kyaukpyu port town project. Risky as it is, Myanmar will have to resort to Exim to fund its own share, given the consortium led by CITIC has agreed to a 30 percent stake for Myanmar.

But one need not look far away to find a way out of this vicious cycle. Any reform of regional order would not be realistic without the participation of Japan, which already has remarkable experience in assisting ASEAN development. Japan’s “know-how” will be critical to help reconcile China’s over-optimistic “play by ear” approach in conjunction with development euphoria and political avarice among local governments.

The estimated demand for airport and other infrastructure projects in Asia will rise to over $26 trillion through 2030, and utterly bankable infrastructure projects should be generated. Japan’s PQI strategy is critical in this regard.

The strategy is supported by government-backed agencies, including the Japan Bank of International Cooperation (JBIC) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which provided funding of $2.204 billion and $69 million, respectively, in 2018, with additional funds from the private sector. In terms of fiscal investment and loan programs in fiscal year 2018, JICA added an additional $5.5 billion whereas JBIC contributed $11 billion. These financial guarantors can reduce the potential risks from market externalities and, to a greater extent, tame the unrealistic expectations of local governments.

In this respect, burden-sharing between the two giants, China and Japan, is surely welcomed. Sino-Japan infrastructure collaboration in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) will establish a possible template for a burden-sharing mechanism. Although it is still under consideration, Japanese companies seem sanguine about partnering with Chinese and Thailand counterparts for a high-speed railway project that will connect three airports in Thailand. Monitored by the JBIC as part of the Japan-led Indo-Pacific economic cooperation, this mega-project will at the same time curry favor with the China-led BRI.

The Missing Soft Infrastructure

A second concern is that, as the BRI has touched a chord with an overwhelming emphasis on physical infrastructure, Southeast Asia has been surprisingly troubled by a lopsided boom in “hard infrastructure,” while “soft infrastructure” — a prerequisite for development — is yet to catch up. Sino-Japanese rivalry over the infrastructure in the region has been intense, and has the targeted countries’ governments racing to chase staggering sums of investment for projects prioritized by the BRI and PQI — namely road, ports, railways, power plants, and telecommunication grids.

In the Philippines, for example, Rodrigo Duterte’s aggressive Build, Build, Build program is meant to spark economic growth through infrastructure. Taking advantage of the geopolitical situation, Duterte has been agitating for Chinese funding while simultaneously scrambling for Japanese concessional loans. It has led to a division of labor, particularly in the railway sector — the northern lines have been offered to Japan while China is responsible for the southern segments. Though such “indirect” burden-sharing is welcome, nonetheless such an approach has its limits. The infrastructure-related debt crisis under Duterte’s predecessors is a clear reminder of how public spending sprees, in cahoots with a cumbersome bureaucracy and corruption, will confound Duterte’s ambition for economic growth. If the booming hard infrastructure cannot march along with the advancement of soft infrastructure – including the delivery of governance, health, education, and cultural services to citizens – the plan will backfire.

In this respect, we need to differentiate between a geopolitical representation that demands rivalry and the empirical realities that call for collaboration and incorporating Japan’s know-how into the BRI. Japan’s BRI policy remains shrouded in vagueness, but we can expect to see it largely as Japanese “constructive engagement,” meant to “incentivize” relevant stakeholders to perform better than their counterparts in establishing sound infrastructure governance.

In relation to this, there are a “thousand faces of China.” The BRI encompasses both well-managed projects run by highly professional companies and “white elephants” that fail to comply with market discipline – and everything in between. This is even more true in Southeast Asia, where “rules” are often too loosely defined. The wide range of Chinese projects – and, for that matter, Japanese efforts — exposes the hypocrisy of trenchant criticism.

Tokyo should not lose sight of the fact that even though Japan in most areas has been doing better, it too had a learning curve. Improving transparency and professionalism is a process, and Tokyo also went through this phase. Decades ago, when Japanese foreign aid implemented a request-based system, funding arrangements often were plagued by risk, such as aiding corruption in the Philippines. For more than a decade, about 10-15 percent of Japan’s Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund loans in the Philippines were siphoned off to Marcos and his cronies by more than 50 Japanese aid contractors. And in the late 1980s and early 1990s, a transnational protest referring Japan as an “eco-terrorist” was mounted against the environmental damage caused by Japanese companies operating in Southeast Asia, including drift-net fishing, trade in tropical timber, and mishandling of land grievances.

Good governance comes at a price and is not easy.

Final Thoughts

Last but not least, in principle, Tokyo’s constructive engagement with the BRI will not only help with China-Japan cooperation, but will also be highly complementary for presenting the best quality of regional development. However, it’s worth noting here that the recent establishment of China’s own courts, under the authority of the Chinese Supreme People’s Court, to handle BRI-related international disputes has rocked the boat. Insofar as Japan is attempting to enforce a free, open, and fair economic zone, Chinese unilateral attempts to provide legal protections for businesses might erode the confidence for potential collaboration.

All in all, the trajectory of China-Japan constructive engagement is at a crossroads. A traditional Chinese proverb says, “One mountain cannot accommodate two tigers.” Will Japan believe it or debunk the myth?

Trissia Wijaya is a PhD Candidate at the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University. Her research interests primarily lie in ASEAN-China relations, state-business relationship, and political economy in East Asia.

Yuma Osaki is a PhD Candidate at the Graduate School of Law, Doshisha University. His research interests are in International Political Economy in the Asia-Pacific region, theoretical and empirical study of regional integration, international trade governance, and foreign policy in Japan and Australia.