There was a time when “a trade war with China” meant real war. During the 1800s, Britain was spending millions on Chinese silk, tea and porcelain, and wanted China to play fair by buying British goods in return. Rebuffed by the Qing Imperial court, the British tapped into a profitable underground demand for opium, imported cheaply from their Indian territories. When Chinese officials tried to stop the traffic, Britain launched the Opium Wars, which ended in 1860 with foreign armies besieging Beijing and forcibly opening up China to international trade.

Within a few years British merchants had established bases in eastern China, and began eyeing untapped markets in the country’s vast interior. But transporting goods inland was slow, unreliable, and expensive: roads were rough and prone to banditry, the rivers full of rapids and pirates, and transport taxes made the cost of British goods uncompetitive.

Looking for a backdoor into China, Britain homed in on the remote southwestern province of Yunnan. British India and Yunnan were separated by just one country – Burma (now known as Myanmar) – which Britain already had her hooks into, following victories in two Anglo-Burmese wars. Yunnan’s mountainous border with Burma was porous, crossed year-round by caravan trains transporting gemstones and raw cotton into China.

Unfortunately, all trade had been suspended by civil war. In 1856 Yunnan’s long-persecuted ethnic Muslims had rebelled against Chinese authority in what the British called the Panthay Uprising. Yunnan became a battleground as Imperial forces fought to stop the Panthays from turning the province into an independent Islamic state.

But it would take more than a war to deter Victorian adventurers. If routes between Burma and Yunnan were blocked, perhaps a British expedition could unblock them and negotiate for a favorable trade deal with whichever side won.

Suspension Bridge on the old Tengchong Road. Photo by David Leffman.

In January 1868 an expedition assembled at Bhamo, a Burmese market town just 30 miles from the Yunnan border. Led by Major Edward Sladen, its initial target was the Muslim-controlled city of Tengyue (today renamed Tengchong), about 100 miles northeast over the Chinese frontier.

Not everyone welcomed Sladen’s plans. Bhamo’s Chinese merchants resented the idea of foreign competition; they also worried that Britain might support Yunnan’s Muslims against Chinese rule. So they hired Li Zhenguo, a Chinese guerrilla fighting the Panthays from his base in the hills outside of Tengyue, to stop the British from reaching their destination.

Even without Li Zhenguo, the expedition’s advance was hampered by local Kachin and Shan peoples, whose sabwas – hereditary chiefs – found reasons to delay these wealthy foreigners in their villages while they milked them for presents and cash. It took Sladen’s party three months just to reach the halfway town of Mangyun, from where they had to fight their way past Li Zhenguo’s stronghold, losing two of their escort in a skirmish. Finally safe inside Tengyue’s city walls, they were interviewed by the Muslim governor, Tasakone, who seemed eager to deal with Britain and promised to send an embassy to Rangoon later that year.

A possible deal in hand, Sladen returned to Bhamo. He concluded that the Panthays would welcome the resumption of cross-border traffic – if Britain supported their cause.

Britain decided, however, not to take sides and in 1873 the Chinese finally defeated the Panthays and reconquered Tengyue. A new expedition swiftly gathered at Bhamo, this time under Colonel Horace Browne. The expedition was to survey a possible railway line to Tengyue and then make a 2,000 mile journey across China to Shanghai. Guarding the expedition were a detachment of Sikhs and Burmese soldiers – a sizable armed force viewed with alarm by the local Chinese authorities.

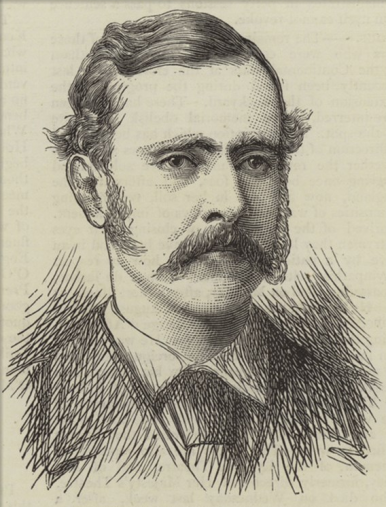

A portrait of Augustus Raymond Margary from his posthumously-published diaries.

Britain now sent a consular official, Augustus Raymond Margary, to meet Browne’s party at Bhamo and act as their interpreter and troubleshooter. Born to a military family in India in 1846, Margary had been in China for seven years; his diaries reveal a patient but determined diplomat, who made friends among Chinese of all classes and worked hard to understand their point of view – even when worn down by delay, illness, and the constant intense scrutiny which all foreigners attracted.

Margary left Shanghai for Yunnan in August 1874. He faced resistance from the Chinese officials he met along his way, who were distrustful of foreigners’ motivations and tried to deter him with dire warnings of the dangers ahead. In fact Margary faced serious trouble on only two occasions: once when he was mobbed by an aggressive crowd; and again while out hunting, when he discovered that the three “deer” he was stalking were, in fact, tigers.

Reaching Yunnan that December, Margary cut southwest across the province toward the Burmese frontier. At Mangyun he found the former guerrilla Li Zhenguo, now a colonel in the Chinese military. Despite Li’s hostility towards Sladen’s expedition, to Margary’s surprise “he prostrated himself, and paid me the highest honors… Li told [the local gentry and sabwas] I had come protected by an Imperial edict, and that they had better take care of me.” Yet Margary was astute enough to wonder if Li might still harbor a grudge against the British.

Margary arrived at Bhamo in January 1875, where he met up with Browne’s expedition and prepared to escort them back into China. At the same time, a small British team was packed off south to survey a longer, more likely route for the railway; but it hadn’t got far when, on February 17, it ran into none other than Li Zhenguo. Li claimed that this back road to Tengchong was blocked by tribal war, and after a week of failed negotiations the survey team was forced to return to Bhamo. In retrospect, it’s likely that this story was invented by Li to get the British to retreat with minimum fuss; it also gave him an alibi for what followed.

Meanwhile, Margary and the main expedition were heading east toward Mangyun. A few days into their journey, reports reached them of an ambush waiting for them on the road ahead. Margary – who had traveled this route safely just weeks earlier – ridiculed the stories as the typical alarmist rumor he’d heard many times before. Convinced that there was nothing to worry about, he went ahead to investigate.

The rest of the expedition camped out in the hills above Mangyun, where Browne made inquiries at a nearby Kachin village. The sabwa appeared polite, but the sheer number of armed men wandering about – and a warning not to worry if they saw any Chinese soldiers – convinced the expedition that something was definitely amiss.

On February 22, Browne awoke to the news that Margary was dead and that a huge party of Chinese and their Kachin allies were about to attack. The expedition had just enough time to take up defensive positions before Kachin swarmed in from the forest, waving spears and screaming battle cries, while the better-armed Chinese held back. Disciplined volleys from the Sikhs soon had them diving for cover, but the battle dragged on until Browne bribed one of the Kachin sabwas to defect to the British side; his men set fire to the undergrowth and Browne’s party escaped. Back at Bhamo, reports confirmed that Margary and four of his Chinese staff had been killed outside Mangyun on February 21, and their heads hung on the town walls.

It says something about the region’s isolation that it took over six weeks for news of the “Yunnan Outrage” to reach the British community in eastern China. Yet this was nothing next to the eight months it took Britain to send an investigative mission to Yunnan – much of the intervening time was wasted in angry posturing on the British diplomatic side, matched by skillful inaction by the Chinese authorities.

Headed by the British Legation Secretary, Thomas Grosvenor, the mission reached Yunnan in March 1876 to find that the Chinese had already completed their inquiries. Yunnan’s governor, Cen Yuying, was a xenophobic, hard-bitten war veteran with a violent temper, though he allowed the Grosvenor Mission to witness a “burlesque of a trial” involving 11 Kachin men accused of killing Margary. The British felt that the Kachin barely understood their interpreter, had no idea of why they were in court, and were merely asked to confirm the Chinese version of events. According to popular gossip, the accused were actually innocent amber merchants, and the Imperial commissioner had been bribed by Cen Yuying to gloss over his role in the affair. Chinese investigators admitted to Grosvenor that none of them had actually visited the murder site.

Margary’s sole memorial is a headstone-like marker in a field outside Mangyun, which reads simply “Site of the Margary Affair.”

Keen to do better, Grosvenor pressed on to Tengyue and Mangyun, interviewing anyone with fresh information: Burmese merchants, Kachin tribesmen, Chinese officials, undercover detectives, French missionaries, and even Li Zhenguo’s mother. Yet each new informant only increased the tangle of contradictions: nobody agreed on who had murdered Margary, why he had been killed, or even where the attack had happened.

So who did kill Margary? The trial named one of the Kachin suspects, La Dou, though Grosvenor believed that the Chinese, keen to deflect blame, had fabricated his confession. Yet all other conclusions – Chinese and British alike – relied on hearsay, rather than hard evidence.

Everyone agreed that Li Zhenguo was involved somehow, though at the time he himself was elsewhere, busy repulsing the railway survey team. Was the murder carried out on his orders by a ragtag mob of opportunistic bandits, Chinese soldiers, or even those 11 Kachin later put on trial?

The British, having briefly blamed the Burmese king for engineering the attack, concocted an anti-foreign conspiracy going right back to Yunnan’s unlikeable governor, Cen Yuying. Under his instructions, Li Zhenguo’s militia had cooperated with Chinese forces to cover the two likely routes that the British might take; while Li dealt with the survey team, local soldiers and Kachin killed Margary and then raced off to attack Browne.

The Chinese denied that any of their soldiers or officials had been involved: they insisted that Margary’s murder was a robbery gone wrong, and the attack on Browne’s party was an entirely separate incident. The guilty parties were Kachin and renegade Chinese in Li Zhenguo’s pay, and the crimes were committed in a lawless region where the British should have known they’d be at the mercy of bandits. They did concede that Li Zhenguo had incited his followers to repulse the British, but insisted that Li had never intended bloodshed: Margary had only been killed after first shooting one of his assailants.

Despite everyone claiming that hundreds of people were involved, nobody aside from those 11 Kachin was ever convicted. All were executed. Li Zhenguo was demoted, while Cen Yuying removed himself from public office for two years, ostensibly in mourning for his mother.

It’s even harder to pin down exactly why the British were attacked because so many people had a motive. Tengyue had just suffered 18 years of bloodshed during the Panthay Uprising, and locals might have seen Browne’s heavily armed expedition as a new invading army. Then there were Bhamo’s Chinese merchants, who would have faced unwanted competition; and the sabwas, who levied tolls on goods ferried through their territories by mule, and stood to lose out had Britain built a railway. Railways themselves were contentious in China, as they were seen as facilitating foreign invasion. Tengyue’s gentry were also concerned that the British would bring with them Christian missionaries, whose presence had divided communities elsewhere in China.

Mule Train sculpture in Tengchong. Photo by David Leffman.

Though big news at the time, Margary’s murder is little remembered today. Its most lasting legacy came from China’s mission of apology to Britain in 1877, led by the scholar-official Guo Songtao. The mission was accommodated at 49 Portland Place, London, which soon became the permanent address of China’s first overseas embassy. Guo’s time as ambassador was not entirely successful: He wrote so enthusiastically about the superiority of Western technology (especially railways) that Beijing eventually forced his retirement.

Margary’s body was never recovered, and his sole memorial is a headstone-like marker in a field outside Mangyun, which reads simply “Site of the Margary Affair.” Nearby, a larger tablet gives the Chinese view of events: That the British attempted to invade China, that local ethnic groups killed Margary, and that their valiant defense of China’s borders would never be forgotten.

Between these two monuments, a minor road still runs to the Burmese border, the descendant of trails followed by the two British expeditions. It never became an important trade route.

David Leffman is a British photographer and travel writer and the author of The Mercenary Mandarin, a biography of the British adventurer William Mesny.