Officials from North and South Korea confirmed this month their interest in cohosting the 2032 Summer Olympics. That this was the case was no surprise: the two countries often use sports as a way to improve relations across the demilitarized zone (DMZ), having formed multiple joint teams for various competitions, including women’s ice hockey at the PyeongChang Olympics, and potential teams for several sports at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics. Recently, a joint North-South Korean team even won a gold medal at the Asian Games, the first such victory for these two countries at a multi-sport event.

However, forming a joint team for a brief period is by no means a good indicator of whether these countries will be up to the complicated task of hosting an Olympics, especially as relations between these two nations can be quite volatile.

The Korean joint bid will compete with bids from several other countries, likely including Australia, China, India, and Indonesia. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) will not announce the official host for some time, giving these countries plenty of time to prepare their bids. The IOC only recently decided to start allowing joint bids, so just a handful of countries have even discussed the idea so far. Considering the lack of precedent, the IOC may have reservations about the first joint bid occurring between two countries with such an unstable relationship.

The complex costs of hosting an Olympics leave many hosts in debt and with infrastructure costs (e.g. stadiums) that have limited use after the games, something cities must consider before making a bid. The IOC has recently tried to mitigate these costs with its Olympic Agenda 2020, encouraging countries to use existing and temporary facilities, but hosting the Olympics still remains costly. For instance, the PyeongChang Olympics cost South Korea just under $13 billion, and questions remain about whether the high price was worth it.

South Korea appears as a viable host, having previously hosted the 1988 Summer Olympics, while, other than the May Day Stadium in Pyongyang, North Korea presumably lacks the appropriate venues to host concurrent competitions.

The possibility of a successful joint bid with Pyongyang builds upon warming relations since the election of South Korean President Moon Jae-in and the unified team from the Winter Olympics earlier this year. The symbolism of a joint bid also plays into broader support for eventual unification. For example, over two-thirds of South Korean respondents in the Korean General Social Survey view unification as necessary, and surveys from the Asan Institute consistently find clear majorities interested in unification. However, South Korean public opinion on aspects of relations with North Korea remain far less popular. In particular, the South Korean public remains very unsupportive of economic aid without a change in the behavior of the North’s authoritarian regime.

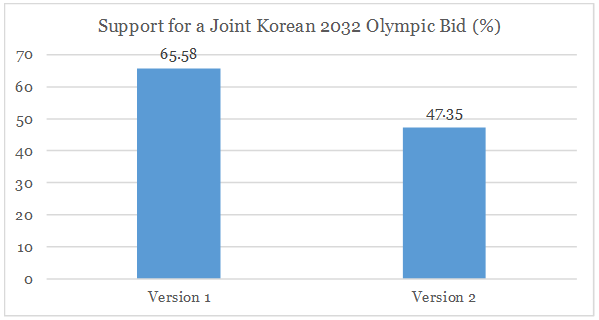

With this in mind, we wanted to identify the extent to which public support for a joint bid was sensitive to how such a bid was presented. For example, a sizable literature suggests that framing and priming effects, especially ones that suggest economic costs, influence perceptions of policy options. To do so, we surveyed 605 South Koreans in the middle of November 2018 via a web survey conducted by Macromil Embrain using quota sampling based on gender and province. We randomly assigned respondents to one of two versions of a question regarding the Olympics. The versions were:

Version 1: North and South Korea have discussed a joint bid for the 2032 Olympics. I would support this joint bid.

Version 2: North and South Korea have discussed a joint bid for the 2032 Olympics. I would support this joint bid, even if South Korea has to help fund the building of Olympic facilities in North Korea.

As seen below, while a majority of respondents favored a joint bid as presented in Version 1, this dropped by 18.23 percent when framed as potentially costing South Korea in terms of construction costs in the North. Among male respondents, the decline is even more noticeable, a 22.52 percent decline (72.19 percent vs. 49.67 percent). Regression analysis further identifies that this pattern endures after controlling for demographic factors (age, gender, income, education), as well as political ideology and support for unification.

What does this mean? The findings suggest that despite confidence-building measures across the Korean Peninsula, South Korean citizens remain sensitive to the costs associated with this interaction. While such sensitivity on its own is unlikely to prevent further discussion on a joint bid, the Moon administration may wish to consider either means to minimize the infrastructure costs in North Korea or attempt to assuage public concerns by focusing on infrastructure with practical purposes after the games.

The survey used in this article was funded by the Academy of Korean Studies (AKS-2018-R05).

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics in East Asian democracies.

Isabel Eliassen is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University majoring in International Affairs and Chinese.