Expectations about the upcoming U.S.-North Korea Hanoi summit centre on a simple assumption: a peace declaration between the United States and North Korea will bring stability and economic development to the whole region. Trump, more than anyone else, seems to believe this.

Does this hypothesis hold water? After a peace declaration, can North Korea simply be re-integrated within the East Asia region and become prosperous?

To answer this question, the Trump administration should have looked at the state of the North Korean economy long before the first summit in Singapore. They would have seen a country that has survived on international aid for its entire existence; a unicum among industrialized societies.

There is debate on whether North Korea has slowly grown inured to aid since the 1990s, or it deliberately stalled economic development to concentrate resources on its military, but there is consensus on its enduring long-term need for aid. A peace declaration seems one of the possible outcomes of the summit, yet how can North Korea and the U.S. envision peace without solving this issue?

A tentative answer should first look at why North Korea is still so poor after decades of assistance. Critics of international aid to the DPRK argue that aid is either disproportionate, it supports the regime or is diverted by it. Is this the case? Has the DPRK received a disproportionate amount of aid, allowing the regime to squander international funds? To test this notion we will first see how much money effectively went to the DPRK, using three sets of figures.

The International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) reports $1.45 billion in aid went to the DPRK from 2001 to 2018. This figure does not include other important aid sources, such as aid allocated and disbursed before 2001, economic assistance from South Korea, and other international contributions that may simply have not been reported to the voluntary IATI mechanism.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) reports a figure of $2.08 billion since 1996, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) data reports $1.62 billion from 1995 to 2016.

The following graph compares the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) North Korea received since the mid-1990s to data from other states. These states are others that have either been associated to North Korea in antagonizing the United States (‘the Axis of Evil’ of Bush fame), are associated with terrorism, or were at war with the United States.

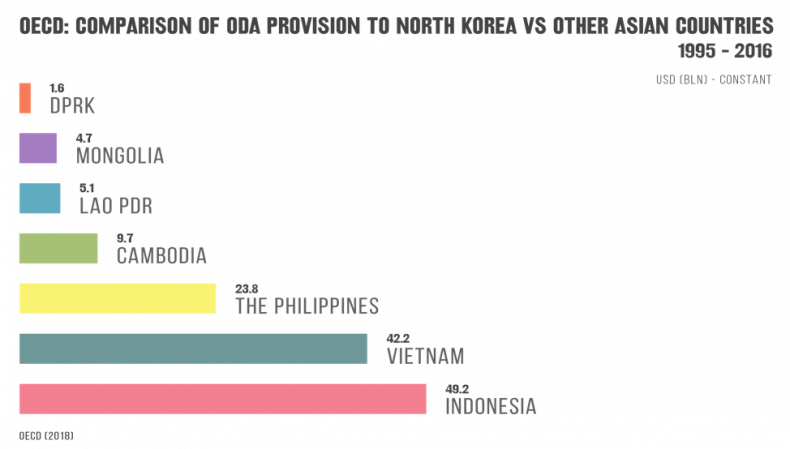

The second graph looks at North Korea in relation to other countries in Asia that shared a socialist economy or have been the recipients of significant aid packages.

The picture is clear: North Korea received much less than other countries sometimes classified as ‘rogue’ or ‘underdeveloped.’

A different issue is whether this aid was put to good use. Previous analysis has argued that the potential for diversion is in fact quite small. Another viewpoint maintains that even if this is true, aid provides the regime with a way of opting out of socioeconomic development.

These debates are useful, but two core points must be clarified. The first is that the North Korean economy was already on a downward trajectory by the mid-1980s. The second is that, starting with the 1995 crisis, aid to North Korea was intended to be humanitarian—that is, for life-saving, relief purposes. Development, or improvement of structural factors, was never thoroughly addressed.

When the United Nations accessed the DPRK in 1995, North Korea was not involved in any active conflict; the government had a de jure commitment to core UN values of the development since the 1980s, and could boast several achievements in childcare, maternity and literacy.

Even in 2014 an independent review of the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) activities in the DPRK determined North Korea was “not a poor country in major crisis,” but “rather isolated, politically and economically.” At the same time, the review suggested that North Korea’s aggressive behaviour brought on increasing sanctions and barriers to development. .

The pre-1995 UN documentation foresaw grounds for capacity-building and development cooperation with the DPRK government. The country appeared to have reached satisfactory levels in many of the developmental standards set by the UN around 1990; up to the summer of 1993 there were no reports of malnutrition.

It is unsurprising then, that when UN agencies took residence in the country in 1995 and gradually mapped the extent of the crisis, they were forced to play catch up. Aid to North Korea has since been characterized by ad hoc interventions, limited access, and partial cooperation on part of the DPRK government.

First, there was the famine and the breakdown of the Public Distribution System (PDS) (1994-1998). This was followed by climatic emergencies, including droughts, floods, and hailstorms (1995-2000). These events spurred increasing environmental vulnerability, and North Korea experienced the recurrence (2003, 2006, 2011, 2016, 2017) of one or a combination of these events.

In the decades since the famine, humanitarian response has compounded from a series of short-term relief efforts into a long-term international aid presence, while North Korea entered an increasingly restrictive regime of sanctions since its nuclear tests of 2006.

Resident UN agencies in the DPRK have established a number of frameworks to maximize aid efficiency and take a more holistic approach. However, these frameworks do not adequately address the fact that the North Korean economy needs profound systemic changes, and those can only come from bold political decisions which are nowhere in sight at the moment.

Can a Peace Declaration Solve Aid Dependency?

Peace in the DPRK should hopefully be accompanied by an adequate degree of economic growth and an end to aid dependency. Without this, a disarmed North Korea risks grave political instability – having relinquished its main source of legitimacy, its nuclear arsenal – which will bring human insecurity and continued vulnerability.

Aid efforts in the DPRK so far have been strictly humanitarian, there has been little to no effect of aid on the North Korean GDP. The prolonged inability to raise people’s livelihood in North Korea should ring an alarm bell for the Trump administration.

Historical and current Gross Domestic Product (GDP) figures indicate severe stagnation since the late 1970s. In this scenario, building Trump branded condos and hotels on North Korean beaches is at best a fanciful dream.

It is troubling that U.S. negotiators have not yet addressed this point in detail, but it is also a difficult area to navigate, given the discrepancy among various sources.

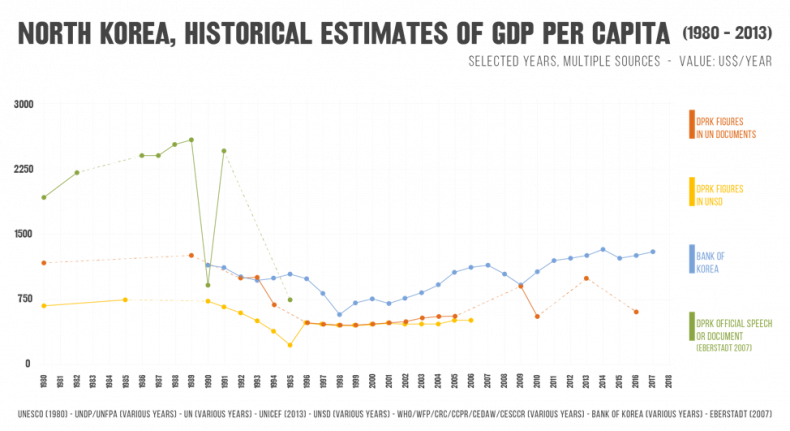

The graphic below shows how divergent estimates of North Korean GDP can be.

There are figures declared by the DPRK, others collected by external actors, figures given as GDP or Gross National Income (GNI), variations of per capita and purchasing power parity (PPP), and finally differences in currencies. Some old estimates used North Korean won, other used current or constant dollars, and others South Korean won.

For example, the GDP reported by the DPRK government in a UNESCO publication for 1979/80 was $1170. The same year, the UN Statistical Division (UNSD) reported a figure of $680 that based on data provided directly by the DPRK Central Bureau of Statistics. Kim Il Sung himself, in his New Year’s 1980 address, declared a whopping $1920.

When the famine was officially addressed by the North Korean government in 1995, GDP figures were given at $222 (UNSD), $1034 (Bank of Korea), $590 (UNDP DPRK) and $719 (DPRK government; later recalibrated to $239 in 1997 and reported by economist Nicholas Eberstadt in his 2007 book about the North Korean Economy).

In more recent years, UN agencies report figures that are just above the $1000 mark ($1013 in 2013). The Bank of Korea gives an average of $1200 in the last five years.

Two concepts should be of key importance to any U.S. policymaker before the summit. The first is that data on North Korea is available, but it requires time and expertise to be evaluated, systematized and then used to inform economic prescriptions to sustain peace. This, rather than easy promises of a “bright future”, should be a guiding principle for U.S. negotiators.

The second and most troubling fact is that no matter what metrics we, use after forty years and a couple of billion dollars of international aid, North Korea has very little to show for in terms of growth. If one looks only at the GDP, the country has gone back to square one – right where it was in 1980. With these numbers, where does North Korea go after a peace declaration?

Overall, we can say that aid to North Korea has brought some improvement since the years of the famine, staving off a bigger catastrophe, but the situation remains precarious countrywide, and the lasting effect of undernutrition could tip the scales further.

The aid flow which contributed to prevent the collapse of what North Korea in the 1990s was relatively small, and it pales in comparison with the funds and efforts that would be needed to support significant, meaningful economic growth, a growth that a pacified and disarmed North Korea would desperately need to justify its own existence.

This is only half of the equation—the North Korean government would need to support sustainable and radical reform, to come out of the woods. It’s worth remembering that even optimistic estimates of the costs for a possible reunification—to bring the DPRK back on its feet without bankrupting its neighbors—float in the region of trillions of dollars. Noteworthy, North Korea is still not a member of any international financial network or institution.

Before a substantial peace – or perhaps even eventually reunification – can be a realistic option on the table, North Korea, South Korea, the U.S. and the international community need to address the economic elephant in the room.

In view of the imminent summit, it would be reassuring to see the White House aggregating expertise on these issues, because despite renewed promises from Kim Jong-un to modernize the country, the current economic condition of North Korea makes a catch-up with Seoul impossible – let alone reintegration within the ranks of the most dynamic economic region on earth – and a peace declaration will not solve that.

This summit – like the meetings that have preceded it – appears to be one by the leaders, for the leaders. The issues explored in this article are vital to the future of the North Korean people; they ought to be on the table, but it’s unlikely they will be, because neither Trump nor Kim seem to have solutions.

Gianluca Spezza (PhD) is a research fellow at the DPRK Strategic Research Center and assistant professor of international relations at KIMEP University in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Follow him @TheSpezz. Nazanin Zadeh-Cummings (PhD) is a Lecturer in Humanitarian Studies at the Centre for Humanitarian Leadership in Melbourne, Australia. Follow her @nzadehcummings. They are currently working on a data-driven book about North Korea, aid, and international cooperation.