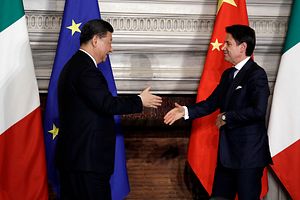

Italy’s Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte received warm praise in Chinese state media when he hosted President Xi Jinping in Rome and formally endorsed China’s contentious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Italy is the first G-7 nation to officially join the BRI, which aims to revive ancient trade routes between East and West. China has promised to reward its supporter with new business opportunities and generous investment in its infrastructure.

For the Chinese media – which always enthusiastically endorses Xi’s actions and policies – it is a classic “win-win” situation. Italy is presented in heroic terms, setting a shining example for other EU countries to follow.

Within Italy, there is much excitement about the reward of Chinese gold. People talk about how they could grow rich selling luxury goods from Milan or hosting more high-spending Chinese tourists in Venice and Rome. The ports of Tauro and Genoa also expect investment and the Italians hope China can lift their country out of recession, bringing good fortune in the Year of the Pig.

The optimism contrasts with a more downbeat tone surrounding the BRI in the press outside of China. Asian countries – including Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and India – have warned of risks, such as political servitude and the burden of unpayable debt.

Even within China, which is facing an economic slowdown, the BRI seems to be slipping down the agenda. It was barely mentioned in the official economic reports that followed the National People’s Congress in Beijing in March.

Italy’s chief cheerleader for the BRI deal is Under Secretary of State for Economic Development Michele Geraci. “We see this as an opportunity for our companies to take advantage of China’s growing influence in the world, especially its commercial influence,” he says.

Alongside the memorandum of understanding (MoU) on the BRI, the Italian government has agreed to contracts worth 2.5 billion euros ($2.8 billion). Geraci claims subsequent contracts may exceed 20 billion euros. Analysts say the deals would be at risk if Italy compromises on its BRI endorsement and denies China its propaganda victory.

The arrangements come at a high political cost for Italy, according to Lucrezia Poggetti from the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin. “Mr. Geraci has been presenting the BRI deal as a framework for Italian companies to export more to China but that is just not true. Germany, France, and the U.K. all export much more to China than Italy does and they have not signed a memorandum of understanding on BRI,” she says.

Poggetti notes that the final version of the deal contains little economic substance. “The text is very political and it’s very symbolic. Basically you’re banking on the fact that a political signature will get you something in return but you’re forgetting that in the meantime you are alienating all your traditional partners, such as the EU, the United States and NATO. And you’re also forgetting that you’re entering into a very unequal partnership with Beijing.”

As China’s economic and diplomatic clout increases, the institutions of the EU are hardening their position. A recent strategy document from the European Commission described China as a “systemic rival promoting alternative modes of governance.”

Furthermore, business leaders in Europe often warn that the Chinese Communist Party is tightening its grip on state-owned enterprises and sometimes moves to veto important business decisions for political reasons. This empowers Xi to exert enormous influence over China’s economic and foreign policy, including its dealings with the Europeans.

During his visit to Rome, Xi said he hoped that Italy “will continue to play an active role in deepening China-EU dialogue and cooperation in various fields and in promoting steady development of China-EU relations.”

That provides Italy with an invitation to step up the podium and praise the benefits of its Sinocentric approach. Geraci is happy to take the stage. He says: “I know this will come as a surprise, but I believe that at this time, Italy is actually leading Europe. We’ve always said we want to take a more active role – something that we haven’t done in the past.”

Geraci believes that other European nations can use Italy’s deals with China as a template for their own arrangements.

However, some EU countries feel that rather than offering leadership, Italy has broken ranks and made the region more susceptible to Chinese domination. “China has discovered that it can pick off EU members and stop the EU developing a coherent policy,” says former EU policy advisor Robert Cooper. He believes that Europe will have more leverage in winning favorable deals with China if it acts as bloc. The EU is China’s largest trading partner and China is the EU’s second largest, behind the United States.

In America, Donald Trump’s administration has openly signaled its disapproval of Italy’s embrace of the Chinese government.

The U.S. National Security Council recently warned that by endorsing BRI, Italy would legitimize China’s “predatory approach to investment” while bringing “no benefits to the Italian people.”

Fabrizio Bozzato at the Taiwan Center for International Strategic Studies says the criticism from Washington has been noted by the Italian government and has met with a mixed response.

In Italy, Prime Minister Conte leads a government built upon a fragile coalition, made up of the populist Five Star Movement (M5S) and the right-wing League party. The Five Star group is keen to assert its independence and is prepared to snub Trump. However, as Bozzato puts it, this government has “two souls and two hearts.”

For those whose hearts are pledged to the League party, there is a widespread view that it is not in Italy’s best interest to put friendship with China ahead of its long-established alliances with Europe and the United States. It was partly under the influence of the League that the original proposals for the deals with China were watered down and reduced to a fairly vague MoU.

Bozzato is also concerned about the implications further down the tiers of government.

“President Xi has said that he wants cooperation at every level but in Italy the politicians at the municipal or provincial level are not at all savvy about China and might not be able to manage the Chinese, who are very smart. Politics at that level is prone to corruption and the Chinese could strike deals which do not benefit Italy at all,” he says.

The recent press coverage of Xi’s trip to Rome showed that Italy’s current government is considered as a friend by China. Yet that friendship will be tested if Italy steps out of line with its allies in order to please Beijing, causing the rifts within the coalition to widen. Italian governments are notoriously short lived, so the controversy threatens Conte’s long-term future.

While he remains in office though, Conte has pledged to “promote the healthy and stable development of EU-China relations.” At his meeting in Rome with Xi, both leaders spoke warmly of multilateralism and free trade. But Lucrezia Poggetti from the Mercator Institute believes the ideology that drives the Chinese government is profoundly different to that which guides political values in postwar Italy.

“The Chinese are not doing the Belt and Road because they want to promote Italian companies — they are doing it to promote their own economic and political interests,” she says.

“Just like any other government, the Chinese government is self-interested. Italy doesn’t have the economic power to deal with Beijing on its own.”

Duncan Bartlett is the Editor of Asian Affairs magazine and a former BBC Correspondent in Asia.