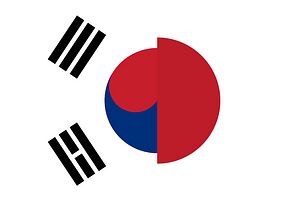

Relations between Japan and South Korea in recent months have again swung to an extreme degree of tension. Lingering grievances over Japan’s colonization of Korea from 1910 to 1945 and a longstanding dispute over rocky islands in the seas between them have fueled several prickly periods over the past few decades. Yet surges in tension over these historic and largely symbolic issues tend to wane when the economic or security interests of either country is threatened.

At the moment, both economic and security interests are at stake. Yet neither side has been willing to retreat from hardline stances. Tokyo has threatened to impose economic sanctions on Seoul in response to a series of recent South Korean Supreme Court rulings demanding that Japanese companies compensate Korean victims of forced wartime labor. And bilateral military cooperation is nearly frozen following a series of maritime mishaps in December and January, one of which involved Tokyo accusing a South Korean naval vessel of locking its fire-control radar onto a Japanese patrol plane.

This situation is problematic for both Tokyo and Seoul, major economic partners that also rely on one another to counter threats emanating from North Korea and to maintain a peaceful, open regional order more generally.

But another big loser from Japan-South Korea tensions is the United States, their shared ally.

Bickering between Seoul and Tokyo plays directly into the hands of Pyongyang and Beijing, who face diminished obstacles in their strategic efforts to dominate the Peninsula and region. Washington is left with fewer options to amplify pressure on these regional rivals via U.S.-South Korea-Japan trilateral initiatives, which in recent years have expanded to include new areas of missile warning and anti-submarine warfare exercises. In Northeast Asia and elsewhere, the rule of strength in numbers applies. The might of the United States dwindles when its regional teammates resist joining the same side of the game.

As the Trump administration navigates freshly perilous terrain in its nuclear and trade negotiations with North Korea and China, it must recognize the losses it accrues from Japan-South Korea rifts and take concerted action to reverse the current contentious trajectory.

At several critical moments in the past, Washington has successfully mediated Seoul-Tokyo tensions, helping to carve a path toward restored cooperation and even the signing of important agreements like the 2016 GSOMIA (General Security of Military Information Agreement). The effectiveness of the United States in this capacity has stemmed from its unique position as a common ally whose support remains critical to both countries, as well as its caution in operating mostly behind the scenes and avoiding taking sides.

Two factors unique to current dynamics present obstacles to Washington’s mediation of this round of tensions.

First, the Trump administration has focused mostly on achieving cost-saving “wins” in Washington’s trade and burden-sharing deals with Tokyo and Seoul in recent months. Efforts to keep alliances on a steady cooperative path in pursuit of broader strategic goals have largely fallen by the wayside.

Second, the domestic dynamics of this particular episode of Tokyo-Seoul tensions make it harder for leaders on either side to back down. The usual actors promoting hardline stances in South Korea-Japan disputes include civic nationalist groups and their allies in the ruling and opposition parties. This time around, powerful actors in the business and military spheres – who normally have either remained aloof from bilateral political tensions or pushed leaders to de-escalate – are aligned on the nationalist side of the equation. That change diminished the usual “de-escalation coalition” that provided leaders with both rationales and political cover to return to “future-oriented relations” in the past.

Neither challenge is insurmountable. As recently as late 2017, the same three administrations were engaged in coordinated efforts to ramp up trilateral military exercises and information sharing and stood in solidarity behind the U.S.-led maximum pressure campaign to counter North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile development. South Korean President Moon Jae-in and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at that time were firmly committed to a “dual-track approach” to bilateral relations, involving deepening cooperation on North Korea and economics even while continuing efforts to resolve differences over the comfort women issue, referring to Korean women who had been forced to serve in Japanese Imperial Army brothels during World War II.

This shows that the Trump administration is willing to shepherd trilateral cooperation and that Moon and Abe are capable of engaging more pragmatically, particularly under conditions of heightened uncertainty with North Korea.

Following the failed Hanoi summit, Washington should revert to its traditional alliance management role and reinvigorate the trilateral cooperation of 2017. This would expand Washington’s range of options to pressure Pyongyang beyond sanctions and reinforce its capacity to address broader regional challenges.

An official readout from a mid-February meeting between U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and South Korean Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-hwa indicated that both sides “expressed their commitment to U.S.-ROK-Japan trilateral cooperation.” That was a good sign. Next, the United States should encourage South Korea and Japan to discuss pathways out of current impasses on forced labor rulings and maritime incidents.

Washington’s mediation this time around may not reap immediate success, but the costs of complacency are certain.

Sitting back and watching Seoul and Tokyo dig deeper trenches will only benefit those on the opposite side of the negotiation table. That will leave President Trump with fewer cards to play in addressing some of Washington’s most critical near-term and future strategic challenges.

Katrin Fraser Katz is an Adjunct Fellow in the Office of the Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. She served as director for Japan, Korea and oceanic Affairs on the staff of the U.S. National Security Council from 2007 to 2008.