This past March 18 marked the five-year anniversary of Taiwan’s 2014 Sunflower Movement, a months-long protest occupation of Taipei’s administrative district, which at its height included half a million people and the occupation of both the Legislative Yuan and the Executive Yuan.

The protests started as a reaction to the Ma administration’s (2008-2016) attempts to hastily negotiate a trade and services deal with China as part of the larger 2010 Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement, which critics say stalled real economic growth in Taiwan, hollowed out the economy, and threatened to force the island deeper into Beijing’s orbit. The Sunflower Movement began as an attempt to slow down the process. Many were opposed to the deal because it was being railroaded through without dissenting voices being heard. The movement is notable for many reasons, chief among them it revealed broad political dissatisfaction across a large spectrum of Taiwanese. Its record numbers, duration (the legislative chamber was occupied for 23 days), impact on the popular culture, festival-like atmosphere, and amazingly low levels of violence and crime had never been seen before. In its immediate aftermath, curation efforts began.

Curation initiatives have been undertaken by Academia Sinica in Taipei, where thousands upon thousands of posters, banners, and protest ephemera have been collected and are being catalogued. The Daybreak project, operated by Sunflower protestor-activist Brian Hioe, whom I interviewed last year, is also developing an online encyclopedia of the movement.

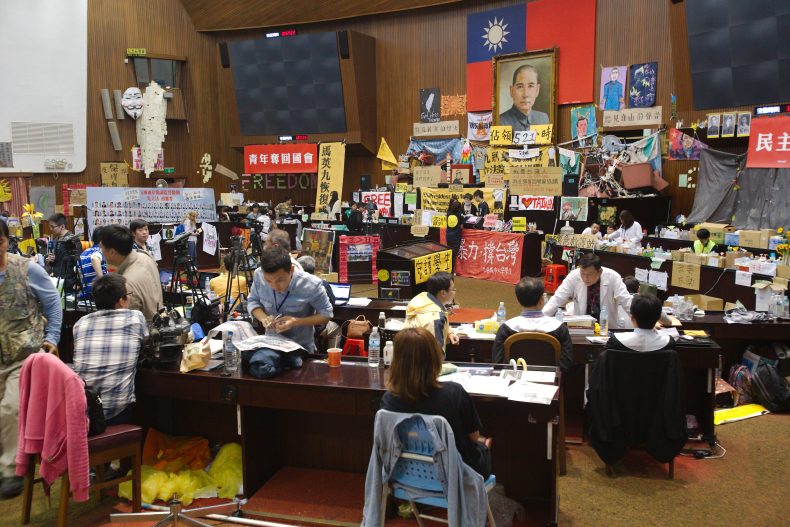

Inside the Legislative Yuan, a jumble of art, donated comfort items, media, communications volunteers, translators – all well-organized and disciplined. Photo by Tobie Openshaw.

Later that same year Ma’s party, the pro-China Kuomintang (KMT), lost to the pro-independence leaning Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in local elections. The DPP would go on to win control of the presidency and legislature in 2016’s national elections. Now five years on, the energy surrounding the movement that led to the DPP surge has dissipated and eyes are turning back to the KMT, which regained a majority of the island’s counties and cities in the 2018 midterms.

Despite the loss of momentum in recent years, the Sunflower Movement still exists in the popular consciousness as something reverential, a “Summer of Love” for the Taiwanese. Now, with the clarity of hindsight, the curation efforts are paying off.

Visitors read the captions for photos displayed at “Sunflowers in the Street: Protest Photographs from Taiwan”on opening day at The Red Room in Taipei. Photo by James X. Morris.

“Sunflowers in the Street: Protest Photographs from Taiwan” is a curation by South Africa-born filmmaker and journalist Tobie Openshaw now on display at The Red Room in Taipei until June 14. Openshaw has lived in Taiwan for 21 years and arrived at the Legislative Yuan after the first day of protests, gaining access to the legislative chamber on several occasions with a press pass issued by France24. On the exhibit’s opening night Openshaw was joined by Chang Jiho, one of the original March 18 occupiers, now a city councilman for Keelung in northern Taiwan.

The original occupiers of the legislature, Chang included, recognized their protest was something bigger than they had expected. In the aftermath, the movement “created tremendous energy for the whole society” explained Chang at the exhibition. Many protest leaders like Chang would enter into politics.

On the ground, the protest movement first occupied the Legislature with sympathetic lawmakers standing guard to prevent police from moving in. As tensions rose, another group attempted to occupy the Executive offices, but were ultimately unsuccessful, being forced out and hit with water cannons. The entire time the protestors made use of social media to coordinate and keep the world updated on events. “The revolution won’t be televised. It will be livestreamed,” says Openshaw.

Wherever people gathered, there were volunteers marshaling the crowds, making sure things stayed orderly and safe. That many people coming together for a single cause — in peace and unity — is a very powerful thing. 500,000 people on a Sunday afternoon. Photo by Tobie Openshaw.

I recently had an opportunity to talk with Openshaw in more detail about his exhibit and how his curation came to be.

The Diplomat: What was your thought when you first arrived at the scene?

Tobie Openshaw: I wasn’t sure what to expect but my first impression was that it was way bigger than I expected and way more real. I could tell that it wasn’t just a sort of random, quick flash mob kind of thing because when I arrived it was a day or two after the occupation started. It was clear they had settled in. I did expect at any time that police were going to really move in. I expected there would be clashes in the street. That’s what I expect from protests, especially being a long running thing, there would be a strong government response. But I also noticed that the sheer number of people there would make it very difficult for the government [and] for the police to actually do something.

… When I was in South Africa, I did my military service there. We have compulsory two-year military service. And during that time we had pretty serious rioting in South Africa. The ANC was working with the stated object of making the country ungovernable. They were setting fire to schools, post offices, they had a slogan: “liberation before education” and people were killed if they were thought to be police informants. … The point I’m making is that I have been on the other side. … Essentially I was ready for anything [at the Sunflower Movement] you know, but pretty soon it became clear […] that this protest was very very strongly built on, working towards, and making sure that it was non-confrontational and that it kept the peace. So very soon I became in awe of the way that the organizers [of the movement] managed to keep a lid on it, defuse or avoid confrontation with the police, and then also from the other side the fact that the government was clearly not overreaching in terms of allowing this protest to happen and not just sending in the cops.

… Coming out from the MRT station I could hear the people singing. They were singing that song from Les Mis — “Can you hear the people sing, singing the song of angry men” but they were singing it in Taiwanese. It was beautiful. I’ve got a recording of it. Just the fact that everybody came out in solidarity, everybody plopped themselves down: “Here I am. Here I’m sitting. I’m taking up this space in order to make my voice heard, but I’m not going to be hurting anybody and I’m not going to be damaging any property.” That just really grabbed me. It was an amazing experience.

I’ve heard a lot of people discuss the event with almost veneration. Do you think the veneration is appropriate? Is it misplaced? Was it just another protest in a long string of Taiwan protests?

I certainly speak of it with veneration… maybe the long-running effects and the results have not been as utopian as one would have hoped — so there’s a certain degree of disappointment now five years later, but at the time, […] as it happened, I feel it’s still worthy of speaking about with great respect and admiration because of the way it was run and managed. … [T]hey basically followed the model of Occupy Wall Street but it was way more effective and successful. They made demands that were reasonable and once the majority of those demands were met they made a decision to leave. … [They] said, “Okay we’ve got six of our eight demands to our satisfaction … so let’s pack up and go home. Let’s go back to our studies. Let’s be responsible citizens, and most of all let’s clean up this space.” And I think that’s one of the really major things that set this apart from any protest that I’ve ever been involved or seen. I saw kids on their knees scrubbing out dirt spots on the carpet inside this building. It really was a very, very moving event and process, and again what you saw there was… you saw and you observed and you lived democracy as it should be practiced. Democracy in action. From protestors, from police, and from the government. They all played the democracy game by the rules and it was beautiful to see.

“The future belongs to her…” Many made the day on the streets into family outings. Photo by Tobie Openshaw.

Now there’s this aura about it these days, but people are a little more bitter. Is the veneration missing the point of the protests at all?

Honestly I don’t think so. … The veneration is about the fact that democracy was seen to be done. And it was done well. Another part of the veneration is the surprise that people felt for how these young kids stood up for their principles and how they managed it. They used to be called the “strawberry generation,” easily squished, easily bruised, and yet I saw kids linking arms and sitting on the floor, as the police in their riot gear and as their water cannons approached. And those kids sat there. They didn’t break, they didn’t run away. They didn’t start crying. They sat and took what was coming to them, and that was sheer bravery. And whether the results in the end are not fully as what one would have hoped or whatever, that you can’t take away from it. The process happened and it happened so well and with such warmth and such support from such a large percentage of Taiwan people.

What is the message you want to convey through your exhibition?

I guess exactly what I’ve been saying: democracy can work. These young people have shown us how to make your voice heard, how to speak truth to power, without damaging things, without breaking things down, without being anarchic. It was a guide or textbook in how to organize efficiently, how to choose your battles, how to choose your battleground, and how to drum up support for the right thing and how to carry that through to a good conclusion.

Journalist and documentary filmmaker Tobie Openshaw (left) and Sunflower protestor turned Keelung City Councilman Chang Jiho greet visitors on the opening day of the exhibit. Photo by James X. Morris.

Of everybody that you saw, they were all young adults — in their late teens, 20s, 30s? Were they young, or were there older people as well?

Certainly the majority were young people. There were students. University students and even high school students. I saw a lot of high school students out there. There were older people. There was a gap in the middle. There were not a whole lot of middle-aged people. That has to be a function of who are the people who have time to go sit in the street. It’s young students and older people who are already retired. The older people I saw there mostly had some kind of agenda — some kind of protest of their own or a topic they were on about by themselves. So I saw nothing of older people guiding or orchestrating anything. That was all the young people. All the people I dealt with in the movement, the spokespeople, the translators… were young people.

Do you consider yourself a curator?

Yes. Absolutely. This exhibition I curated to emphasize those things that I mentioned: the organization, the youth … the other players. This is how far-reaching it was. That kind of thing. I did try to bring in as many elements as possible. But they are all things that I observed. There’s nothing there of the inner workings of the leadership group, because I was not privy to any of that. And another part that I hope my exhibition shows is that expats who were in Taiwan who were either journalists, photographers, or just interested came there. There were many complaints this wasn’t getting enough international attention. I mentioned this in my talk. It was hard to get the international media to understand the nuances of what was going on.

They wanted violence and you had no violence.

Yeah. They just wanted the clashes. But what I wanted to show with my exhibition was that yes there were outsiders looking with an outsider’s eye, and this is what they saw. And I tell that story because that’s the only story I have… the outsider story. That’s the story that is mine to tell.

Chang An-lo, also known as “White Wolf,” of the Chinese Unification Promotion Party shows up with a crowd of rowdy supporters to challenge the students, April 1, 2014. Photo by Tobie Openshaw.

Not all of the photographs are yours. With the exception of Chang Jiho, all of the photographs are by outsiders — people not born and raised in Taiwan. Do you think this impacts the perspective of your exhibition? Does it impact the way that it’s been curated? Does it impact the message?

Yes… But I also certainly don’t feel that our perspective strays very far from the accepted narrative of what the Sunflowers stood for and what it meant for Taiwan society. There’s certainly nothing radical about our interpretation. We maybe noticed or commented on or found particularly touching some things that to Taiwanese people would not be unusual.

You’ve been here for the past five years. Now we’re seeing a swing back to the KMT, and this populist perspective of some of the candidates… Do you see another movement of that kind of scale and energy occurring again in Taiwan?

I sincerely doubt it. Events like this have a time and a place where everything comes together and the time is right and the atmosphere is right for everything to happen. And I don’t see that happening here anytime soon. Also I know that, for instance, a couple of years ago the KMT tried to orchestrate something similar and it completely colossally failed. There was something like “oh yeah they’re clearly trying to have another Sunflower Movement” because they saw how effective it was the previous time and they tried to turn the tables, but I think the dissatisfaction at the moment is very broad and it’s devolved into various interest groups… the LGBT protest, the pension fund protest, but none of them have captured the popular imagination the way the Sunflowers did. I think events like that of that scale and of that depth and that intensity are extremely rare in the world.

… Another factor is the government, having had that experience the first time around, probably, I expect, would act more quickly and more decisively before something like that takes hold. It was hugely disruptive to the government at that time so I’m pretty sure they’ve sat around the table and said, “If this ever happens again you shut that building down, you turn off the lights, whatever it takes. You get those people out of there and stop that thing before it takes hold.”

Inside the Legislative Yuan, a jumble of art, donated comfort items, media, medical volunteers and, to the right, law students who volunteered their time to give free legal advice. Photo by Tobie Openshaw.

How long have you been in Taiwan?

21 years. I photographed the [2008 Wild Strawberry Movement] as well. I literally just swung by, didn’t understand what it was about, and it was very small. They were camped out in front of Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall and I just took some photos there and got an idea. But I was also aware from an early-ish stage that the Sunflowers — because it happened so quickly and seemingly out of the blue — it was something that had been coming up in steps from the past.

You were able to gauge this would be different from the Strawberries?

Yeah. Just in terms of scale, the moment I arrived there I could see “wow this is big.”

Do you think that’s part of this veneration? This aura? That it’s something that’s completely different from what had been in the past?

Absolutely. It’s also for me, what I’ve been trying to say about it in my exhibition, is this is the best of Taiwan. This is Taiwan. Because anywhere else in the world it would have probably gone very differently. In South Africa it would have gone way differently. In America with Occupy Wall Street it went differently. In Hong Kong it went differently. So yeah, it is pretty damn unique and is a testament to Taiwan and Taiwan’s people that it went the way it did.

The exhibit “Sunflowers in the Street: Protest Photographs from Taiwan” can be viewed at The Red Room in Taipei until June 14, 2019.