Last week, U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin traveled to Beijing to discuss a potential resolution to the ongoing trade war between the United States and China.

With the Wall Street base case projecting tariff stabilization, various members of the business community, including those working within the manufacturing and agricultural sectors, are beginning to breathe a collective sigh of relief.

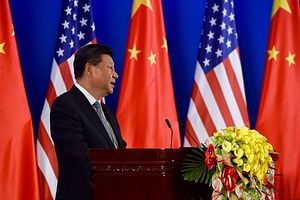

Across both countries, there is hope that significant domestic economic pressures such as last week’s inversion of the American yield curve and the widespread impact of declining Chinese exports will push Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping to reach an agreement as soon as possible and work towards gradually lifting any remaining tariffs.

Despite these encouraging developments, heralding in the sunset of the Sino-American trade war may yet be premature. The various hostile interactions between Washington and Beijing over the course of the last twelve months demonstrate a historic shift in modern trade war tactics that go beyond the presence—or lack thereof—of customary duties and excises.

If tariffs represent the ammunition of choice in traditional economic warfare, the actors of today’s conflict employ a much more complex array of weapons—including judicial targeting, pointed sanctions, encumbered bureaucratic processes—that create a dangerous slippage between economics and politics and imply the long-term destabilization of both capital markets and the postwar diplomatic order.

Most conspicuously in recent news cycles, both Beijing and Washington have openly endorsed the use of theoretically independent judicial proceedings as bargaining chips in economic negotiations.

Following the Canadian arrest of Chinese telecom device manufacturer Huawei’s Meng Wanzhou on charges of U.S. sanction evasion, Trump publicly admitted to considering using Meng’s extradition to gain the upper hand in ongoing trade discussions with Beijing. “If I think it’s good for what will be certainly the largest trade deal ever made,” he told reporters in December, “I would certainly intervene.” This sent a message heard around the world: if the U.S. doesn’t get what it wants in trade discussions, anything is on the table – including executive intervention in judicial matters.

China responded to Meng’s arrest by first detaining Canadian citizens in a move of officially acknowledged retaliation and subsequently increasing a Canadian drug smuggler’s sentence from 15 years to capital punishment.

In addition to blurring the boundaries between national security justice and economics, the U.S. and China have coupled the use of politically-motivated sanctions with an escalation of regulatory travel and financial barriers.

After several Five Eyes member states pledged to follow the American lead in banning Huawei from involvement in their respective countries’ 5G networks, Beijing restricted Canadian canola oil and Australian coal imports, as well as delayed a joint tourism project with New Zealand. By exerting economic and diplomatic pressure on some of the U.S.’ closest partners, Beijing undoubtedly seeks to rattle key Western alliances.

Across the Pacific, last October the U.S. announced a heightened government review of foreign investments and non-controlling interests in U.S. companies. The new rules endow the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CIFUS) with a broader mandate to specifically scrutinize potential takeovers within the high-technology industry that could pose intellectual property theft threats. While the general enhancement of national security is the program’s official aim, many see this as yet another underhand attempt by the U.S. to gain the upper hand in strained trade negotiations. The recently announced sale of Grindr, the world’s most popular dating application for members of the LGBT community, highlights the trials faced by Chinese buyers of U.S. businesses who do not properly adhere to CFIUS regulations.

Although some, such as former Japanese Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda, have likened the current Sino-American trade war to the competition between Japan and the U.S. in the 1980s, several key differences between these two economic rivalries underline the gravity of what is at stake today. In addition to China’s economic growth relying less on exports than Japan’s did then, China shares neither a common political nor national security vision with the U.S. In this light, going beyond tariffs makes sense. The actors on today’s stage are moving past the use of standard trade war tools because the current fight is not simply about economic primacy; it is an ideological struggle between different models of global governance.

Up to a point, turning to untapped points of leverage is standard behavior among nations experiencing trade tension. Indeed, such conflicts are often dubbed trade wars for the very fact that they inflict significant economic damage.

But the ease with which both Washington and Beijing have turned to unprecedented political and personal attacks should concern observers. Even if these competing powers can pull together a ceasefire in the ensuing months, the erratic and intractable nature of their new trade war arsenals will continue to call into question the future tenability of both trade and treaties alike.

Cybele Greenberg is a research associate focused on International Economics at the Council on Foreign Relations. Jonathan Jeffrey is political risk consultant and writer based in Washington, DC.