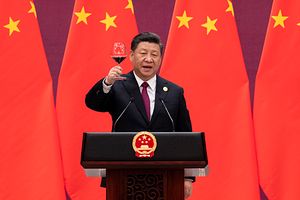

The Second Belt and Road Forum is officially underway in Beijing, bringing with it a host of government leaders from around the world. But who, exactly, is coming — and just an importantly, who isn’t? And what does the attendee list say about the Belt and Road Initiative as a whole?

In a March interview with People’s Daily, Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi mentioned that “about 40” foreign government leaders would attend. The final count, according to Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s press conference on April 19, the week before the summit, was that “heads of state and government from 37 countries” would attend. However, Wang included Indonesia in the list of 37 countries, while Jakarta was actually represented at the 2019 BRF by Vice President Jusuf Kalla.

That brings the final total of heads of state or government in attendance to 36 (not counting host Xi Jinping), represented by the map below. For the full list, including a breakdown by region, click here.

What does this tell us about the Belt and Road?

First, the BRI is booming in its core regions: China’s immediate periphery. Perhaps the greatest success is in Southeast Asia. China secured the attendance of top leaders from nine of the 10 ASEAN member states, with Indonesia being the lone exception. That’s likely due to the close timing after President Joko Widodo’s re-election bid rather than a deliberate snub. Clearly, despite frictions stemming from the South China Sea and lingering concerns over the debt tally of BRI projects, Southeast Asian governments are still keen on the project.

Another notable success is Central Asia; four out of the five regional countries sent their top leaders (arguably – Kazakhstan’s representative was former President Nursultan Nazarbayev, but he is still the de facto leader). The lone holdout, Turkmenistan, is notoriously adverse to multilateral cooperation projects and made for an unsurprising no-show in Beijing.

Second, despite a wealth of recent headlines about Europe’s reservations toward China, European countries accounted for one-third of the BRF’s top-level attendees – 12 of the 36 heads of state or government were from Europe (if Russia and Azerbaijan are included in this category). EU heavyweights like Germany, France, and the United Kingdom didn’t send their top leaders, and indeed these countries – particularly Germany and France – have been the most vocal in expressing concerns. But some of the smaller European countries remain highly interested in the Belt and Road, and interest has only grown since the first BRF in 2017. New top-level attendees from Europe include Austria, Azerbaijan, Cyprus, and Portugal (interestingly, despite all the fuss over Italy officially signing a BRI accord with China last month, Italy’s prime minister was also in attendance in 2017). In other words, China’s BRI is experiencing a healthy growth of interest from Europe, despite some pushback from Brussels.

The BRI has seen similar growth in Africa. In 2017, just two heads of state from African countries made the trip: Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn and Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta. This year, that figure jumped to five, with the top leaders of Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Mozambique all present in Beijing. The BRI’s expansion to Africa is a relatively new development, but it seems to be finding fertile ground thus far — at least along the eastern coast of the continent, which is a more natural fit for the initial “Silk Road” billing of the BRI.

But not everywhere is seeing the same success. South Asia remains notable for the absence of top-level representation. India was a pointed no-show, as it continues to be deeply concerned that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor passes through territory occupied by Pakistan, but claimed by India. But New Delhi wasn’t alone in passing up the chance to send a top leader to the 2019 BRF. Of the eight South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation member staes, only Pakistan and Nepal sent their heads of governments to Beijing.

East Asia is another obvious blank spot – Mongolia was the only country from China’s own region to send a top leader. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in, and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un (never likely to come to such a large-scale international gathering) were all absent.

From the Middle East, only the UAE sent top-level representation, showing that the BRI has been slow to take hold in the region despite its prominence on the historical Silk Road and China’s friendly ties with major regional powers like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Israel.

South Asia and the Middle East are particularly notable because they should be along the ‘natural’ route of the Belt and Road, at least as it was initially conceived of. Though the BRI has essentially grown from its Silk Road-redux origins to be a truly global project, there is less interest in the regions that were not originally put on the BRI map. Despite a nascent BRI push into South America, Latin America, and the Caribbean, for example, only Chile sent a top leader to this year’s forum. And from the Pacific Islands, the subject of major concerns about Chinese “dept trap diplomacy,” the only top-level attendee was Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister Peter O’Neill. Clearly Beijing has more work to do to grow the BRI outside of the Silk Road’s historical region of significance.

One final note: another notable no-show was, of course, U.S. President Donald Trump. While he was never expected to attend, the United States went a step further and didn’t send any representatives from Washington to the massive gathering. In 2017, Matt Pottinger, the National Security Council’s senior director for Asia, ended up attending; this year even he didn’t make the trip. It was one of the few set-backs for China compared to two years ago, and says a lot about the current state of U.S.-China relations.