In April 1875, the British in eastern China awoke to appalling news: one of their consular officials, the interpreter Augustus Margary, had been murdered two months earlier along the country’s distant southwestern border with Burma (today’s Myanmar). Margary, who spoke fluent Chinese, was on a mission approved by the Imperial Qing court at Beijing, carrying passes demanding that authorities along the way give him their full assistance – and yet he had still been killed. The incident suggested that no foreigner could count on traveling safely in China, whatever the assurances offered by Chinese officialdom. Spurred on by an outraged press, the British government demanded a full investigation.

In the end nobody could agree on why Margary had been killed, who had killed him, or even exactly where the attack had taken place (his body was never recovered). The Chinese version of events was that Margary had been attacked by lawless hill tribes while crossing a notoriously dangerous frontier area, well outside the bounds of their protection. The British, however, believed that a local militia had ambushed Margary near a sizable town, with the approval – and probably the direct assistance – of Chinese officials. After months spent interviewing everyone involved, British investigators concluded that the murder was part of an anti-foreign conspiracy going right back to the abrasive provincial governor, Cen Yuying. Though their suspicions were never proved, the British accused Cen of being “the chief criminal” in the affair, branding him – rather bluntly – as “The Cruel Viceroy.”

The only known image of Cen Yuying.

The Chinese view of Cen Yuying is more complex. He was born in 1829 at the village of Nalao Zhai in Guangxi province, into an ethnic Zhuang family who had once been hereditary chiefs. Because Cen showed early literary promise, his father worried about him becoming a mere bookworm and had him trained in martial arts as well. As a youth he came first in the local government exams, but his father’s death around 1849 left him head of the household with no time for further academic studies. When the Taiping Rebellion broke out in 1851 he organized a militia to defend his home county and was later proposed as an assistant magistrate. But following a dispute with another official Cen fled to Yunnan province, where his military skills found him work defending mines from banditry.

In 1856 Yunnan’s substantial Muslim Hui population, long persecuted by the Han Chinese majority, launched a violent uprising against the Qing government. Under their leader Du Wenxiu, they took the western city of Dali as capital of an independent Islamic state. Cen immediately offered his services to the government, but an attempt to recapture Dali failed and the Chinese were driven right back across Yunnan to the provincial capital, Kunming, where they were besieged for the next three years by the fearsome, battle-scarred Muslim general Ma Rulong. Unimpressed by local Qing forces, Cen returned home to Guangxi and raised his own sizeable militia. In 1859 he led them back to Yunnan and recaptured several rebel bases, zeal that got him appointed acting prefect at Chengjiang town.

By now Ma Rulong was losing enthusiasm for the war and renewed his attack on Kunming, hoping to force the Chinese to sue for peace. His ploy worked, and in 1864 Cen was sent to hammer out the terms of Ma’s surrender: in return for switching sides, Ma’s troops would be granted an amnesty, while Ma himself was made a general in the Chinese military and put in charge at Kunming. For his own role in the negotiations, Cen was elevated to acting lieutenant-governor of all Yunnan, a huge promotion.

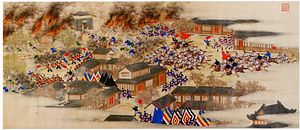

Not that the war was over yet. Leaving Ma Rulong to defend the capital, Cen departed for Yunnan’s mountainous eastern border, where he spent three years battling ethnic Miao insurgents who had spilled over from their own uprising in neighbouring Guizhou province. He had barely completed his task when, in 1867, Du Wenxiu dispatched a 200,000-strong Muslim army from Dali in a final attempt to capture Kunming. The recently-installed Chinese governor hanged himself in panic and, with Ma Rulong badly outnumbered, Cen was recalled as acting governor. Aided by his understudy, the vigorous, hunchbacked Bai warlord Yang Yuke, Cen managed to liberate Kunming in November 1868. As Cen and Ma Rulong fanned out to pacify eastern Yunnan, Yang Yuke fought his way west toward Dali, systematically retaking rebel strongholds along the way. Following a six-month siege, Dali surrendered to Yang’s forces in December 1872 and Du Wenxiu committed suicide, ending the Muslim Uprising. A few days later Cen arrived and ordered the wholesale slaughter of Dali’s Muslim population. Ten thousand men, women and children died in this one incident alone, enough to fill two dozen large trophy baskets with severed ears; in total, it’s believed that 5 million people – half of Yunnan’s population – were either killed or displaced by the war.

In the wake of his conquest, Cen was officially confirmed as governor of Yunnan and so found himself in charge when Margary was murdered in 1875. The Qing court, resentful of British demands to have Cen at least removed from his post for his role in the affair – if not actually prosecuted – were relieved when his stepmother died in 1876, requiring Cen to retire from public office for three years. Cen settled at Guilin, then the capital of Guangxi province, were he built a grey brick mansion just outside the old Ming palace walls on East Alley, complete with a private school for his children.

The building to the left is Cen’s mansion in Guilin, which still stands today. Image by David Leffman.

The official mourning period over, Cen was next appointed governor of Guizhou province, where the British adventurer William Mesny found him in 1879. Mesny, resident in China for almost 20 years, had spoken out about Cen’s supposed role in Margary’s death and now found that his Chinese friends avoided him in case they risked Cen’s wrath: “even my wife and her relations trembled with fear, lest they should suffer on account of their relationship with me.” And their fears seemed justified when, the following year, Mesny himself was assaulted and nearly killed in circumstances very similar to Margary’s murder. Convinced that Cen had tried to have him assassinated too, Mesny spent the next decade vilifying him in the English-language Chinese press, triumphed at his death, and even went on to accuse his son, Cen Chunxuan, of cannibalism.

Meanwhile, trouble was brewing in southwestern China. France was gearing up to annex Vietnam, which shares a border with Yunnan province; China had no wish to have France as a neighbor and anyway considered northern Vietnam to be a vassal state. But China had already suffered humiliating military defeats at the hands of Western powers and wanted to avoid an open confrontation. Cen suggested using a pro-Chinese guerrilla army in Vietnam, the Black Flags, to fight the French covertly on China’s behalf, and in 1883 was given the joint governorship of Yunnan and Guizhou provinces to coordinate the campaign.

Chinese involvement didn’t stay secret for long, and after the key Vietnamese city of Sontay fell to the French in December that year, their forces openly joined in the fray: “A bloody engagement ensued, which lasted two days and two nights. The corpses of the slain Frenchmen lay strewn all over the country, their blood flowing like rivers; while the soldiers of China attained a glorious and complete victory.” But this triumphant report – originally believed to have come from Cen – turned out to be completely bogus. Following a bitter, two-year struggle, both the Black Flags and Chinese were routed and driven out of Vietnam through the Zhennan Pass, where they unexpectedly rallied and finally defeated the French. It wasn’t much of a victory: the war cost the lives of tens of thousands of Chinese troops (and the destruction of China’s southern navy), and China ended up having to accept French occupation of Vietnam in return for having demands for hefty war reparations dropped.

Almost all Chinese officials involved in the war found themselves demoted afterwards, though Cen himself was soon rehabilitated, and on his 60th birthday was even sent presents by the emperor and granted hereditary titles. But he had also contracted chronic malaria in Vietnam, which steadily wore him down. Increasingly ill, Cen was granted leave of absence and, shortly after returning to his post, died at Kunming on June, 6 1889.

From a modern perspective, Cen’s early career as an undoubtedly skillful negotiator and military tactician is badly marred by his massacre of Dali’s civilians at the end of the Muslim Uprising in 1872. His actions followed a pattern typical for victorious Chinese generals during the 19th century: one notorious episode during the contemporary Taiping Rebellion in eastern China saw perhaps 40,000 people slaughtered at Suzhou, after the city had surrendered to Chinese forces. As to Margary’s murder, Cen’s complicity remains unproven – though it was certainly in Britain’s interest to accuse him, as they used the threat of Cen’s prosecution to squeeze diplomatic and territorial concessions from the Qing court. In 1876 Thomas Grosvenor, head of the mission investigating the Margary affair, met Cen and described him as “a thick-set man of 48 years, a very dark complexion, stolid but outspoken in manner, and evidently of pronounced temper … States that in his youth he could walk, when not engaged in military affairs, 30 or more miles a day. He now prefers a horse. Does not smoke or drink wine. Has been in Guizhou and S. Sichuan, and throughout Yunnan. Is apparently not liked by the officials of the province on account of his temper.”

Death brought official forgiveness for Cen’s failure to keep the French out of Vietnam, and the emperor Guangxu even wrote him a glowing memorial:

Cen Yuying was a man endowed with a loyal and patriotic nature, combined with solid attainments and tried experience… The sudden news of his death has moved Us to the most profound sorrow, and We command that the title of Grand Tutor be conferred upon him, that his name be enrolled for worship in the Hall of Distinguished Worthies, and that a temple be erected to his memory in the capital of Yunnan… We allot Tls.1000 to be paid from the Treasury of Yunnan, as a contribution towards defraying his funeral expenses. All the penalties incurred during his career are hereby remitted, and the Board concerned will memorialize Us respecting the bestowal of posthumous honors on the deceased Viceroy, which shall be on a scale suited to his exalted rank. The local authorities en route will make due arrangements for the conveyance of his remains to his native place… These commands We issue in token of our high regard and affectionate remembrance for a loyal and devoted Servant.

Cen’s tomb outside Guilin. Image by David Leffman.

Cen’s tomb is located 6 kilometers outside Guilin on the southwestern flanks of Yao Shan. From the road’s end, a muddy path climbs to a sloping hillside where a grove of trees surrounds the grave site. Hidden by long grass, four tablets dated Guangxu 15th Year (1890) sketch out Cen’s career, while a tall pillar, a paifang memorial gateway, and a pavilion sit in the open on the slope above, flanked by a single decapitated statue of an official. The site has been robbed several times: Cen’s body was dragged out, the tomb goods pilfered and, in 2012, the monumental stone guardian animals were stolen (though later recovered by the police, they haven’t been replaced). At the top of the slope are two graves, Cen’s on the left and his stepmother’s to the right, both decorated with Imperial dragon reliefs – a high honor. Stumps of red candles on the altars in front commemorate recent visits by his descendants, many of whom live overseas. The fengshui is superb – matching the ideal requirements of “A green dragon to the left, On the right a white tiger” – with a protective hill rising behind and the tombs facing south over the Li river to distant karst outcrops.

David Leffman is a British photographer and travel writer and the author of The Mercenary Mandarin, a biography of the British adventurer William Mesny.