Rubaba Mohammadi, 19, never seemed to suffer directly from the long war in Afghanistan. Mohammadi may have born and raised during the war, but she never crossed an improvised explosive device. She has never been caught in the crossfire or an airstrike. But she used to stay home all day long on her own. She’d watch her siblings going to school, graduating, attending weddings, and going on holidays. Mohammadi was confined to her home, not because she was wounded by a suicide bombing but because she was born partially paralyzed.

Mohammadi suffered from neglect under the weight of her disability, amid a turbulent and troubled Afghan society, until she wiped off her tears to pick up a colored pencil. In 2013, she produced her first ever painting using her mouth.

“I used to feel helpless and weak before painting,” says Mohammadi, adding a smile. “That old Rubaba is no longer here… I never thought I could rock the world with my art.”

Rubaba Mohammadi, 19, paints at Rubaba Center for Arts and Culture in Kabul. Image Credit Ezzatullah Mehrdad

In Afghanistan, chronic violence not only claims countless lives but also weighs heavy on the shoulders of the country’s youths. Disabled people are very often left behind. The war shatters everyday life, and Afghanistan’s youths, disabled or not, have limited opportunities.

To cope with the side effects of the war, educated people, particularly youths, turn to arts and books to emotionally survive. In creative works, they seek to thrive in a country that has sunk into violence and misery over four decades of relentless violence.

“I began painting five years ago due to being left on my own at home all the time,” Mohammadi, says, describing the journey of building a career and a profession in painting. “I couldn’t go anywhere, I couldn’t go school.”

Mohammadi gathered her courage and dared to draw a vase full of fruit, a painting that took her a year and a half using her mouth. She threw away her first drawing.

“I used to stay up late nights crying and wailing at God and asking Him why me,” she remembers.

“Everyone looked at my physical appearance, but no one saw what I have been going through at the corner of my home.”

But Mohammadi started enjoying painting. Staying home turned into a privilege, rather than a prison. She could focused on painting. “I don’t know whether my father liked me or not, but I am sure my mother never liked me,” she said of the time before she began drawing. After she began painting, Mohammadi became the pride of her family. “My painting won me the heart of my mother.”

Mohammadi came out of the shadows and has held exhibitions in major art centers in Kabul. In October 2018, she held an exhibition at a show in Turkey for disabled artists, representing an Afghanistan on a world stage that gives her nothing in return. Mohammadi built a profession, reputation, and career out of a life that always seemed unfair to her.

She opened social media accounts and has connected with thousand of fans. Mohammadi is a celebrity. “I want to express my dreams, my feelings, and my world through my painting,” says Mohammadi.

After five years of painting, she sold her works and saved money to open a center, named the Rubaba Center for Art and Culture (RCAC), where many students come to learn painting, public speaking, music, and other handicrafts.

Students along with Rubaba Mohammadi, in a blue headscarf, pose for a photo at the Rubaba Center for Arts and Culture in Kabul. Image Credit Ezzatullah Mehrdad

Mohammadi printed out business cards: “President and founder of RCAC,” they read. She has a secretary who enrolls new students and sets up her meetings. Every day, she wakes up in the center that she runs, works and paints for two to eight hours, studies English, and plays music.

“It disappoints me that the government does not support disabled people,” says Mohammadi, who wears a blue headscarf. “I want to build a school and university for my fellow disabled people.”

Art is not the only tool Afghan youths use to deal with the war and, more, to thrive. In the last decade of reconstruction, though the war continues on, a new generation of book addicts has grown up. Although Afghanistan’s literacy rate is as low as 38.2 percent, educated Afghans read regularly to emotionally survive.

“Book readers have high self-confidence,” says Dr. Jafar Ahmadi, an independent psychologist in Kabul. “The more people read books, the better they are functioning and leading their daily lives.”

Sohrab Sorosh, a writer in Kabul, never went to fight on the front lines for the army or the police, or the Taliban. Sorosh’s luck has not run out; he’s avoided being caught in bomb blasts. But he suffers from the emotional toll of the war: “In the burdensome moments, book reading is the best hobby.”

Born and raised during the war, Sorosh had always had a deep passion for books. Back when he was young, curling up with books was his hobby. “My uncle had two boxes full of books,” Sorosh recalls. “I read few of the books, and I saw mostly the photos in the books. Well, my siblings did not even see the photos.”

Sorosh graduated from sixth grade but could not continue his schooling. Nevertheless, he never stopped reading. In late 2000s, Sorosh immersed himself in books and began regularly borrowing from a library in Mazar-e-Sharif.

“[My writing] is the result of book reading,” says Sorosh, who landed a career in journalism and writing. Sorosh has become one of the best narrative writers in the country. He works with a well-regarded newspaper and has drafted a short story collection ready for publication.

Abdullah, 38, dropped out of school after eighth grade. He sells books in the heart of Kabul. “Every night, I read 10 pages before going to bed,” says Abdullah, who goes without a surname. “I feel inner peace by reading books after a long day in busy street selling books.”

Abdullah sells books of every genre, from novels to get-rich self-help books. His table displays translated version of the best sellers, including Michelle Obama’s Becoming and John Kerry’s Every Day is Extra.

Those Afghans who have tasted the sweetness of reading hope to transfer the habit to Afghanistan’s future generations. A side effect of the long war has been the neglect of children; so many go without proper education and many lack the opportunity to read fairy tales before going to bed.

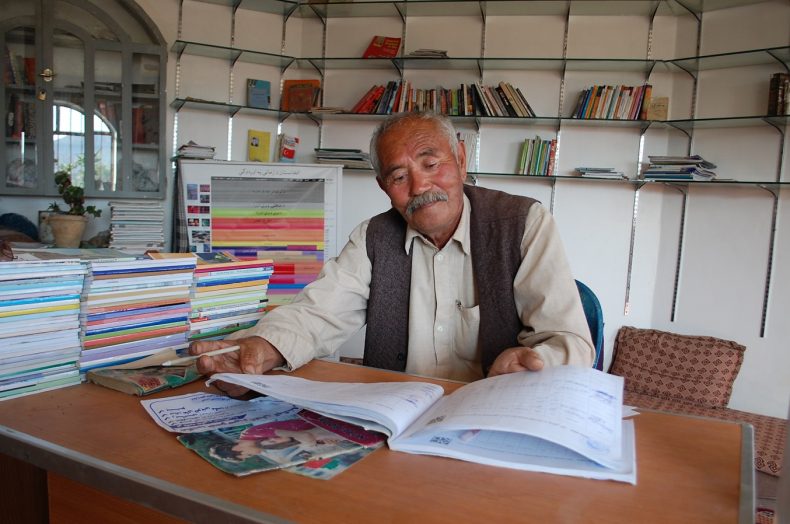

Abul Ali Payk, 65-year-old co-founder of Shirin Library, sits behind desk of Shirin Library in the outskirts of Kabul, Afghanistan. Image Credit Ezzatullah Mehrdad.

Once, in the west outskirts of Kabul city, schoolboys chased a dog around the neighborhood and caught him in a ruined house’s yard. The boys tied a rope around neck of the dog and hung him up. Abdul Ali Payk, a 65-year-old resident of the neighborhood, saw the boys hanging the dog. He rushed over to save the dog.

“I really suffer from the social inadequacy,” says Payk, who was a book addict and used to run a shadow monthly named Payk Melat in remote areas of Ghazni province during the war against the Soviets in 1980s.

Heart broken and upset, Payk returned home, where his daughter, Rabia Salihi, greeted him. Payk told his daughter the story and they decided to establish a mini library for the neighborhood boys, named Shirin Library. Maybe books could save Afghan youth from the cruelty and war around them. The father built the library and his daughter campaigned to find books to stock it.

“The library is my life,” says Payk, laying down in the library. “If the library was not established, I would have a heart attack.”

Ezzatullah Mehrdad is a freelance journalist based in Kabul.