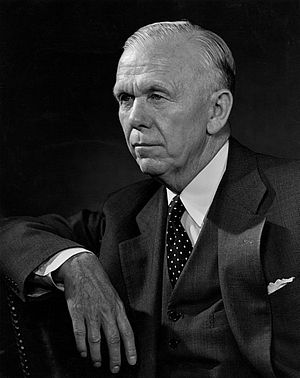

Shortly after the end of World War II, President Truman dispatched one of his most senior military officers, General George Marshall, to China in order to broker a peace between Nationalist and Communist factions. Truman and Marshall believed peace to be possible, and (influenced to some extent by the U.S. Army mission during the war), Marshall believed that leaning on Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists was the best way to achieve this peace. By 1947 Marshall would leave China, the civil war in full swing and his mission in shambles.

We have an extensive literature on the war years, starting with Barbara Tuchman’s important but flawed Stilwell and the American Experience in China. The U.S. had not ignored China during the war, but it never gave Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalist government the resources it wanted to fight both the Communists and the Chinese. The “China question” was of considerable salience in the United States in the immediate post-war period, with missionaries, the business community, and anti-communists all expressing interest in the outcome of the civil war.

Daniel Kurtz-Phelan’s The China Mission (reviewed here by Qingfei Yin and here by John Pomfret), brings additional detail to the post-war period. Using a variety of Chinese, American, and Taiwanese sources, Kurtz-Phelan argues that the failure of Marshall’s mission reflected an incoherence in the U.S. approach to China, especially with respect to the balance between patron and client. He also argues that the failure helped Marshall develop his approach towards rebuilding Europe in the late 1940s.

Part of the issue was that different parts of the government had a different vision for China. Everyone hoped that China would resist Soviet expansionism, and there was even optimism about the CCP’s attitude towards the Soviets. The State Department held out hope that the Republic of China could become a robust democracy. The War Department (and eventually the Department of Defense) hoped that China would become more robust, perhaps less democratic. This disagreement would bring incoherence to U.S. policy, as well as lay some of the seeds for Senator Joseph McCarthy’s critique of Marshall and the State department.

Indeed, Marshall’s time in China offered grist to McCarthy, who viciously attacked Marshall for being “Losing China” was one of the core allegations made by McCarthy and his ilk against the State Department, and many China experts lost their careers for insufficient enthusiasm about Chiang Kai Shek’s prospects. Chiang himself believed that Marshall had forced a post-war cease-fire that worked to the benefit of Communist forces.

Kurtz-Phelan argues that the failure of the China mission helped inform Marshall’s approach to reconstruction in Europe. Marshall appreciated that the United States could not write a blank check to the post-war European governments, but also that it could not expect too much of them during their period of weakness. What became the Marshall plan reflected this belief, providing the foundation for reconstruction but leaving much of the responsibility to the recipient governments. The success of the Marshall Plan was perhaps not predicated on Marshall’s failure in China, but the latter undoubtedly influenced the former.

The views expressed here are his personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Army, the Army War College, or any other department or agency of the U.S. government.