On Friday, U.S. President Trump and China’s Vice Premier Liu He announced a trade agreement that saw Washington suspend tariff increases while China agreed to purchase some $40-$50 billion of agricultural products, including pork. Behind this seemingly positive development, the financial markets rallied; the Dow Jones rose some 320 points or 1.21 percent. Trump billed the agreement as “phase one” of a broader trade agreement, but behind the soaring rhetoric belies a key motivation for the deal: The Chinese need pig imports.

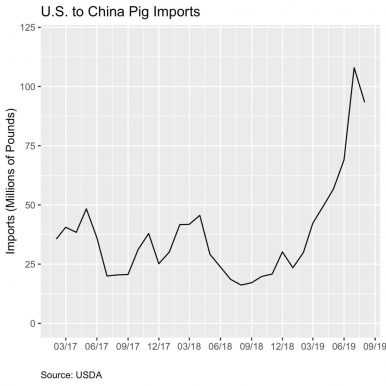

The truth is that even before the deal, Chinese imports of pigs from the United States was already increasing. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, Chinese imports of pork from the United States more than tripled from 23.4 to 93.4 million pounds from January 2019 to August 2019, with the imports generally increasing throughout this period.

The increased imports are because China’s pigs are suffering from an African swine fever epidemic. African swine fever is a highly virulent virus that, although harmless to humans, can cause death within a week in pigs. So infectious is this disease that Dutch bank Rabobank predicts China could lose 20-70 percent of its domestic pig herd this year, potentially around 350 million pigs or a quarter of the world’s pigs. To prevent further transmission of the virus, more than 1 million pigs were culled. Since China annually slaughters about 700 million pigs a year, this virus has affected nearly half of the country’s annual consumption worth of pigs. As a result, China’s pig prices have hit multi-year highs of 28 yuan ($3.96) per kilogram, up 47 percent from last August; Rabobank predicts that prices may further increase past 30 or 40 yuan per kilogram. Furthermore, pig price increases have squeezed the Chinese consumer, pushing food inflation to nearly 10 percent.

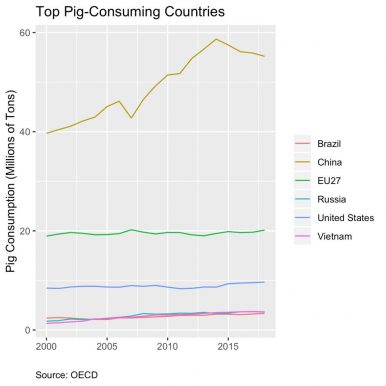

The importance of pork in daily life cannot be overstated as it is used in dishes such as twice-cooked pork or stuffing in dumplings and symbolizes prosperity. In fact, China is the world’s largest pig consumer, more than the next five regions (i.e., EU 27, United States, Russia, Brazil, Vietnam) combined.

Consequently, the increased cost in pork has produced frustration in the local population. On Douyin (known as TikTok internationally), users have posted videos lamenting the high prices deterring their consumption. One user bought one the size of his finger, as “the price of pork has gone up so much that I seriously cannot afford eating it.” Another rubbed onions and carrots of a porkchop to grab the flavor without consuming the meat. Fights have even broken out over its shortage.

"Pulled" pork? These women in China were filmed fighting over the last piece of discounted pork at a market pic.twitter.com/WSEq4r9fG6

— SCMP News (@SCMPNews) September 20, 2019

As rising living standards, of which pork is considered part of, are a key part of the Chinese Communist Party’s mandate, China has taken measures to deal with this pig shortage. The state has auctioned off 10,000 tons from state reserves to deal with supply, although such measures amount only to 26-180 thousands of pigs, assuming a typical pig weight of 110-770 pounds. This, of course, is a rounding error when compared to the number of pigs annually consumed in the country. Furthermore, Quartz reported that senior leaders have spoken about the price increase and that the “government has announced subsidies for setting up new farms, removed tolls for the transport of live pigs and frozen pork until June next year, and urged lenders to finance pig farming endeavors.” China has even experimented with breeding unusually large pigs, more than 1,100 pounds or as large as polar bears, to ameliorate the shortage. Ultimately, these measures stop short of solving the root problem: There are, at the moment, not enough pigs in China.

Faced with the magnitude of this challenge, the Chinese had no choice but to import to ease the shortages. Luckily for China, the United States is the next largest country in terms of pork production. Giving the “concession” to purchase pork would not only help the Chinese domestic pig crisis, but also ostensibly engender goodwill for future trade talks. Given that China had imposed 72 percent duties on American pork before the epidemic and willingly imported an increasing amount during the year, thereby voluntarily incurring the heavy duties, it must be recognized that the Chinese “concession” in buying pigs was borne not primarily of goodwill, but of necessity.

Perhaps, there will still be a grand trade deal, but long-running issues such as currency depreciation and intellectual property have not yet been solved. When combined with the facts of the Chinese pig epidemic, investors and pundits should not read too much from the Chinese gesture to buy more pigs as a positive signal for future trade developments.

Andy Law is an economic analyst who has written various papers on financial issues. He holds a B.S. in economics from Yale.

Note: Pig import data is from the United States Department of Agriculture and pig consumption data is from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. The figures were generated using the statistical software R.