“An independent Tibet would have created [a] much different India altogether,” a 2018 article assumes, musing on an alternative history: One in which the United States and India stopped China from annexing Tibet in the 1950s. The text was published in the Organiser, a magazine put out by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu nationalist organization in India. The RSS is like a twin brother to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the party that now rules India. Most BJP politicians belong to the RSS; this includes the prime minister, Narendra Modi.

The RSS may be a twin brother, but it is also the older one (the one born a bit earlier, so to speak). It was the RSS that created the BJP and gave it an ideological direction. The RSS continues to influence the BJP in many ways. And yet, despite the twins’ bonds, the younger brother has a life of his own. BJP policies are usually in tune with the RSS’ worldview, but certain significant disagreements have also occurred, with the RSS being the more radical of the pair. The party-organization has a different perspective of the economy (I wrote about this for The Diplomat earlier). The other, hardly-ever mentioned aspect is Tibet.

During the last five years, Modi avoided a direct confrontation with China, maneuvering between a harder and a softer approach. The Doklam face-off was an exception. New Delhi could have grasped more points of leverage in its wrangling with Beijing and yet chose not to, as if not wanting to provoke its stronger rival too much.

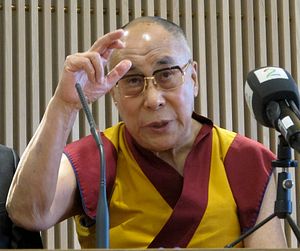

One of those unused weapons was Tibet. Hosting the Tibetan government-in-exile and the Dalai Lama on its territory provides India with a card to play against China, and yet New Delhi has never done so in a hard way. It kept recognizing Beijing’s rights to Tibet right since the 1950s. The policy did not change under Modi. In 2014, he invited the head of the exiled government to his swearing-in, but did not repeat the same for his second swearing-in in 2019 (the same happened with representatives of Taiwan). A few other events in 2018 showed that New Delhi distanced itself from the Tibetan government-in-exile, a step further than usual. History and morality are on the Tibetans’ side, but realpolitik is not; the power balance is completely tilted to Beijing’s side.

The RSS, however, has a much stronger view of Tibet and China. In 1960, a headline in Panchjanya, the RSS’ Hindi mouthpiece, called the independence of Tibet India’s “moral responsibility.” In 1962, during the high emotions of the Sino-Indian war, RSS leader M.S. Golwalkar declared boldly: “Let the Dalai Lama […] declare the independence of Tibet. Let us give him all necessary support in carrying on the struggle for his country’s freedom.”

In 1999, the RSS launched a Bharat-Tibet Sahyog Manch (An India-Tibet Cooperation Forum), but it must be admitted that this body has remained remained obscure. In 2010, the other RSS mouthpiece, Organiser, lamented that the New Delhi “has failed to lift even a little diplomatic finger on their [Tibetans’] behalf” (at that time, however, the Indian government was not led by the BJP and the RSS found it easier to criticize it publicly). In 2017, the RSS started a campaign to confer the highest civilian award in India, Bharat Ratna, on the Dalai Lama.

This partnership appears to work both ways. The Tibetan spiritual leader is visibly in contact with the RSS, as he is seen at the Hindu nationalist organization’s events from time to time. He had been in touch with even some of the more radical of them, such as Ashok Singhal. In 2014, he visited the RSS headquarters. The “RSS has always been with us in our struggle for Tibet,” he declared at that

The Dalai Lama and the Tibetans are important for the RSS not only for foreign policy reasons, but also ideologically. Buddhism was, after all, born in South Asia. Before it spread to various quarters of the Asian continent, including the neighboring Tibet, it had grown as a part of the Indian civilization. The extended vision of Hinduism, as presented by Hindu nationalists (and not only them), perceives Buddhism as a part of Hindu traditions. Moreover, the spread of Buddhism is a proof how historically Indian culture influenced other regions. It therefore suits the RSS’ vision of the glory of ancient India.

This historical connection is often stressed by the RSS but sometimes also by the other side too. In 2014, the Dalai Lama and RSS leaders attended the World Hindu Congress (an event in Delhi). “Ancient India was our guru,” the Tibetan spiritual leader stressed on that occasion, adding “not modern India, it is too westernised.” This is the kind of verbal honey the RSS likes to taste.

The 84-year-old Dalai Lama is well aware that once he dies, the Chinese will use the process of spiritual succession – a search for the reincarnation of the deity within him, as his followers believe – to find his successor in China, therefore gaining control over his religious authority. He has therefore suggested that this will lead to the emergence of two Dalai Lamas: one in China and another in India. This means that the office of the Dalai Lama will remain an issue in Sino-Indian relations even after the demise of the incumbent. Aside from this, the presence of an exiled government and a Tibetan diaspora in India will remain the two other issues.

As of now, it seems only a few less-known BJP politicians, such as B.S. Koshiyari, utter the “independence of Tibet” phrase. Of late, the only first-rank Indian political leader to raise this call was not a BJP member but Mulayam Singh Yadav, a regional leader from Uttar Pradesh, the founder of the Samajwadi Party (Socialist Party) and the BJP’s sworn rival. It is easier to say so when in opposition, which is where Yadav now is.

For now, the BJP will most possibly continue with keeping the Tibet card buried deep in its deck. There may be two processes that can modify its standing, one external and the other internal. Externally, this could happen in case of a surge in Sino-Indian tensions. Internally, the RSS was able to push the BJP harder on issues on which they differed when the past BJP governments became weaker. The second scenario is unlikely now, with BJP’s safe majority and Modi’s immense popularity.

Moreover, diplomacy is usually not black-and-white and usually grey. Given its track record, New Delhi is unlikely to suddenly talk of openly Tibet’s independence. But there are other, less sharp blades Delhi could pull out to be stronger, but not too provocative. As Aakriti Bachhawat pointed out for ASPI, India could hypothetically retort to such means as “using ambiguous language on Tibet’s status, issuing stapled visas for Tibetans[…] and ramping up engagement with the Tibetan government in exile.” At any rate, it is possible that in case of a sharp rise in Sino-Indian tensions, the Tibetan issue may resurface in the countries’ bilateral relations. But in case they will remain moderate, the same subject may be confined to the ideological backstage of India’s ruling party.