Watching the latest images from Hong Kong, the world holds its breath. Protesters and police alike have become increasingly violent, leading to bloodshed and first casualties on both sides. Calls for restraint and de-escalation are coming from many directions, most recently from the European Union and Australia, but no end is in sight and some observers fear that the unrest might grow into a long-term, Northern Ireland-like conflict. For sure the hostilities will take longer to heal with every day they last.

However, to blame the situation entirely on Xi Jinping or to suggest that only he holds the solution in his hand, as Gideon Rachman did some time ago in the Financial Times, misses the point for two reasons. First, because the underlying reasons of the “revolt,” as Rachman calls it, are much older and not tied to Xi. And second, because the situation is too complex for Xi or Beijing to be able to solve this problem alone.

To better understand the aggressiveness on both sides and the underlying reasons, it is necessary to look back in history far beyond Xi’s rise to power in 2012 or even the handover in 1997. In doing so, it is helpful to distinguish two perspectives, namely that of native Hong Kongers, and that of Mainland Chinese. The perspective of the former has been brilliantly analysed by Chris Lonsdale in the South China Morning Post, which even as an opinion piece is surprising as the paper is often said to be under increasing influence from Beijing. Lonsdale argues that a large part of Hong Kong’s population fled from the massive destruction of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s — and from the Communists in 1949 one should add — so that its identity is characterized by a severe internalized trauma and the collective fear that Hong Kong and its freedoms will one day fall victim to the Communists again.

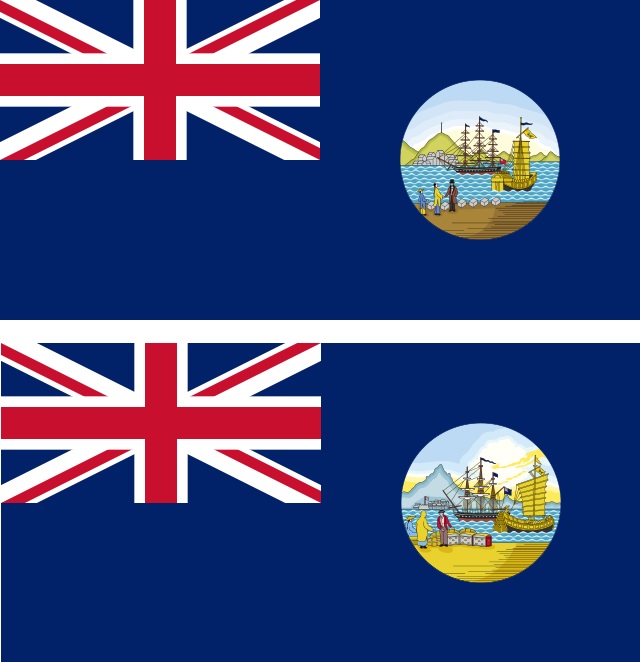

The Hong Kong colonial flags from 1876-1955 (top) and 1955-1959 (bottom). Images from Wikimedia Commons/ Sodacan.

The perspective of Mainland China, meanwhile, is that Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan are scars from European and Japanese colonialization and expansion, which can only heal by bringing them back under Chinese control. Before the last British Hong Kong flag, which was pulled down in 1997 to be replaced by the red Bauhinia flag, Hong Kong had from 1876 onwards two other colonial flags showing the Union Jack and a scene of British and Chinese traders and ships. The images may appear innocent, but they epitomize the humiliation still felt today of the island (which can be seen in the background) being bitten off by foreigners when China was too weak to prevent it. So the Mainland Chinese trauma, starting with the first Opium War in 1840, is more than 100 years older than the Hong Kong trauma that started in 1949. It also was handed down to the current generation as something that must be overcome and never forgotten, so renouncing Hong Kong — or giving up its goal to reunite with Taiwan – is out of the question for Beijing.

As cruel and inhumane as its ramifications might be, the historic mission of the Communist Party to restore and maintain China’s geographical integrity, including Tibet and Xinjiang, is not an invention by Xi, but dates back to the Party’s foundation in 1921. As pointed out by the legal scholar Jiang Shigong after the 19th Party Congress in 2017, with his “new era” Xi Jinping places himself as the culmination point and completer of this Party mission, along the line of a simple narrative: “China stood up under Mao, got rich under Deng, and is now becoming powerful under Xi.”

As obsessed as it is with its mission, the Communist Party is equally consumed by requiring each Chinese citizen to “love the motherland,” a slogan that serves the Party well. In this context it is very telling what one young protester sprayed in traditional characters (those used in Hong Kong, while the Mainland uses simplified ones) on a barricade: “After the system has changed, I will love China.” “System” refers to the formula of “one country, two systems” enshrined in the Basic Law, under which Hong Kong has been brought back, and Taiwan is supposed to be brought back, to China. While some observers have already noted the death of this concept, which might or might not be true, the protesters are making the wrong assumption that the other of the two systems — i.e. the Mainland regime — will or can change. This simply is not going to happen.

With some parts of Hong Kong having become a war zone, it is imperative to first bring professional mediators in to help bring down the emotions on both sides. Then it is important that representatives of the protest movement (regardless of how decentralized it is) and the Hong Kong government start talking and listening to each other, acknowledging and respecting each other’s above-described traumas and limitations and together find a way out of the impasse. Realistic and feasible demands are that (1) the protesters stop all destruction and violence, (2) the police equally stop all violence and allow independent investigations into previous abuses, and (3) the government addresses underlying social and economic issues such as housing and employment. But system change is not a realistic demand, not in Hong Kong and even less so on the Mainland.

Patrick Hess is a senior financial market and China expert with a long private and public sector experience and fluency in Mandarin. His publications and teaching experience, currently at Goethe University Frankfurt, focus on China’s economy, financial system and policymaking.