The world since mid-November has seen an unprecedented series of leaks of internal government documents from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) concerning its human rights abuses against Turkic peoples in its western region. The PRC, noted for its tight Communist Party discipline and harsh punishment of transgressors, is often referred to as a “black box” by Sinologists. For them as much as for anybody else, these leaks come as a surprise. Indeed, they are a testament to the courage of some within the PRC, an indication of how bad Beijing’s human rights abuses must be, and possibly a crack in the façade of Xi Jinping’s power over China.

The Content of the Leaks

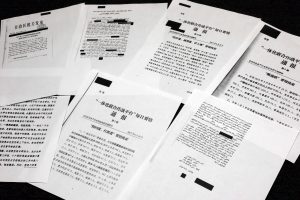

On November 16, the New York Times published the first watershed story detailing the extraordinary lengths the People’s Republic of China has gone to to carry out — and conceal — its massive program of ethnic “re-education” against Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in its Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which these peoples commonly refer to as East Turkistan. It is based on 403 pages of internal PRC government documents smuggled out by an unnamed official seeking only to “prevent Communist Party leaders, including Mr. Xi, from escaping responsibility for the program.” These documents, termed the “Xinjiang Papers,” represent the first time a trove of such size and importance has been exposed.

The Times lists among these documents previously unreleased speeches by Chairman Xi and other Chinese officials, reports of population control and surveillance, and investigations into local officials deemed inadequately zealous in carrying out Beijing’s campaign. Although the Times has summarized and highlighted the main content, it has thus far made only 15 pages available online.

Close on the heels of this release came another major leak on November 24: 24 pages of documents internal to China’s Xinjiang government, mainly detailing procedures to be used in running mass internment camps for Turkic peoples. The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ, a non-profit organization noted for spearheading the release of the Panama Papers) received and analyzed these “China Cables,” which the Times noted were “provided by Uighur overseas networks.”

The China Cables consist of a telegram and three bulletins from 2017 detailing measures required for stricter security at internment camps. Also included is a court document from 2018 sentencing a Uyghur Communist Party member to 10 years in prison for “spreading halal… and haram” in 2009.

Observing these leaks closely was Adrian Zenz, a scholar at the forefront of independent research into these human rights abuses. Zenz’s pioneering work put the lie to Beijing’s deception campaign in 2018. This month, he reported that he had “obtained a cache of over 25,000 files from different government departments” in 2019, comprising a large collection of population data suggesting the harsh conditions Beijing is imposing on Turkic groups. All of the documents above went into his recent detailed analysis of the available information.

We should note that Uygur and East Turkistan nationalist groups and other organizations are providing critical information about PRC abuses, as well, for example by collecting reports from released prisoners and detailing the location, condition, and number of internment camps.

What the Leaks Tell Us

In some ways, this official information does not reveal much new. China’s imprisonment of a million or perhaps many more Turkic minority persons was well known. Its objective of deracination was plain to see, meaning the eradication of any identity other than Zhonghua Minzu (中华民族), i.e. Chinese ethno-nationalism.

However, there are numerous invaluable facts to be gleaned. Dated June 2017, most of the China Cables show the extreme level of security being put in place even prior to Beijing’s claims about not having camps or humane treatment in the camps.

From the Xinjiang Papers, we see Xi Jinping’s call for an all-out “struggle against terrorism, infiltration and separatism” using the “organs of dictatorship” and showing “absolutely no mercy,” as well as Xinjiang party secretary Chen Quanguo’s orders to “round up everyone who should be rounded up.” This constitutes a direct linkage between PRC leadership and the abuses on the ground.

Zenz’s work provides statistical verification of these abuses, including:

- The intensive security apparatus Beijing has developed to carry out its internment campaign;

- Its official endorsement of “assault-style re-education” measures;

- Seriously depressed birth rates for Uyghur areas of Xinjiang since 2016 (along with generally depressed national birth rates, even after essentially removing the One Child Policy);

- The focus on “removing male authority figures from families”;

- A “new speculative upper limit estimate of 1.8 million or 15.4 percent of adult members of Xinjiang’s Turkic and Hui ethnic minority groups, and a new minimum estimate of 900,000 or 7.7 percent… in previous (since spring 2017) or current extrajudicial internment.”

If the language of these documents seems mild to readers, they should understand the system described therein as the Party’s “idealized” version of reality. For example, in the Xinjiang Papers document answering questions of children of disappeared parents, the repetition of the phrase “no need to worry” (不用担心) should not be taken at face value. Rather, it is an ominous, euphemistic way of referring to a terrible circumstance.

In a broader sense, the need to hold incommunicado residents who have broken no laws, the mood of extreme denial and anger in Beijing, the evidence of abuse already at hand, and the horrified reaction of multiple Chinese officials should make clear that prisoners are enduring what the Party dare not reveal.

Areas not addressed in these releases include Beijing’s recent claim to have released most of the prisoners, which we should assume to be as reliable as many of its other claims. Emerging details concerning abuses like forced organ harvesting, although not yet verified, are consistent with a PRC leadership lacking concern for human rights.

Why and Why Now?

In a Communist Party of 90 million, it may seem insignificant that a few would leak internal documents, but that is not so. Having followed Chinese affairs closely for some 15 years myself and speaking with others who have spent multiple decades in the field, these leaks appear to be unprecedented. Breaking Party discipline is tantamount to treason, and thus we have only seen it in cases of power grabs such as those of Lin Biao and Bo Xilai.

One relatively minor case of a leak is instructive: The unmasking of a Shanghai censor’s attempt to squelch a story on a prominent investor’s suspected child molestation. In cases that shock the moral sense, the will to act against the Party may be kindled. Even so, for a Party member to make public internal documents on a matter of extreme state security is an act we have only now witnessed.

What makes a Communist Party official risk life and limb to smuggle the truth out of China? In normal times, very little. Indeed, there is less to hide, along with an extraordinarily high cost for disobedience. What these leaks should signal is that China is not in normal times. The government’s actions have fallen so far outside its rhetoric of providing for citizens’ welfare — and so far outside the realm of acceptable human conduct — that resistance is building. The most patriotic officials would rather face death than obey quietly. That it is occurring at all is an historic event and shows at least serious questioning of Xi’s authority.

As the PRC’s international presence grows, each nation will have to decide how they are to receive it. No matter warm or cold, each should be clear about the sort of government they are facing. China may object to any hint of disagreement but, like everyone else, respects strength of conviction. Could there be a stronger display of conviction than the courage of these officials? The better we remember their example, the better able we all will be to deal with an increasingly strong China.