One of the pillars of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that remains continually overlooked is people-to-people ties. P2P, to use the shorthand, is about building social, cultural, and digital entanglements. Social scientists have long understood the power of networks and the political realities they can produce. The BRI aims to build networks across multiple sectors, far beyond trade and infrastructure. Here then the Silk Road plays a key role: a narrative of history as connectivity and civilizational dialogue invented in the late 19th century, which today has become a platform for creatively building networks and connections between cities, regions, and institutions.

In December, the BRI-Silk Road nexus took an altogether new direction to focus on the shared history of sports and their civilizational roots. A high-level six-day “Summit Forum on ‘Belt and Road’ Communication of Sports Civilization and Cultural Exchange” took place in Taiyuan, in north China’s Shanxi province. The forum brought together delegates from across Asia. Chinese party leaders from various ministries and departments, and sports organizations participated, as did archaeologists, historians, and experts from cultural sector institutions. Seven live broadcasts of the event were watched by more than 8 million viewers.

Keynote speeches focused on Silk Road heritage, sports cultural exchanges, and the development of sports for promoting the BRI. Well-known mainland and foreign academics offered reports on a series of issues, notably the establishment of cultural self-confidence, ancient cultural exchanges along the Asian Maritime Silk Road, and the histories of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean martial arts.

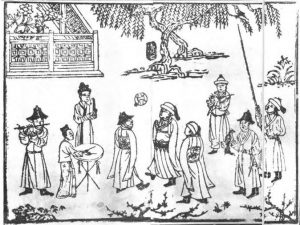

The stated purpose of the event was to respond positively to President Xi Jinping’s proposal for the co-construction of the Belt and Road, use sport to promote cultural exchanges between China and other countries, and, in so doing, help promote the sports industry in Shanxi. Such events align with the aims of building P2P connections, and in this case, this meant framing sports in terms of their civilizational roots and routes. Traditional sports, from board games to folk games like swings, are a part of Shaanxi’s cultural strength and vigor. Other presentations showcased different dynasties of Chinese history to speak of a civilizational sporting heritage. In linking sports to the Silk Road story, archaeological records, mural paintings, cave art, and written texts become the means for finding points of connection between China, Japan, India, Pakistan, Thailand, and others.

Events like the Taiyuan forum help us better understand the routes by which martial arts, archery, wrestling, tamari, board games, horse polo, chess, mask, swings, cuju, or weightlifting moved between regions and populations historically. Chinese sources testify to 5,000 years of history in Shanxi, including a diverse sports culture, some of which is recorded in stone, ceramics, sculpture, and paint. Coming on the back of the National Comprehensive Sports Meeting and the Second National Youth Games, Shanxi is embedding contemporary leisure pursuits in a deeper history, one that places the province at the heart of a national, perhaps even Asian, common heritage.

But the language of “common” or “shared” cultural heritage invariably leads to the more difficult questions of origins, sources, and even ownership. At the surface level, the Silk Road is a story of exchange, dialogue, and openness. But once it becomes operationalized as heritage, it inevitably becomes a question of designation, claiming, and even possession. Across Asia, this has been the story of the past few decades, as cities and regions — and, most stridently, states — have sought to capitalize on culture and heritage for tourism development, branding, and identity building. The fights between Indonesia and Malaysia over batik exemplify how everyday, seemingly unpolitical traditional cultural forms can become a vector for nationalism and hostility.

The P2P element of BRI is unleashing complex cultural politics. As we know, the co-opting of civilization in international affairs raises the stakes significantly. Tracing the roots of games such as chess, polo, equestrian sports, and martial arts through the canons of imperial China and its ethnic histories, and then linking them to a story of cross-cultural, cross-border exchange, exemplifies the new territories of history-making we are now entering through the Belt and Road. Artwork and artifacts are being mobilized to tell certain stories and historically locate regions within Beijing’s strategic futures. Across Asia today, the past remains something that continues to be “wrestled” over, and the BRI-Silk Road nexus is moving the pieces around the board in unpredictable ways.

Rani Singh is a Ph.D. Candidate, University of Western Australia working on Silk Road geoculturalisms and cultural corridors of BRI. Tim Winter is a Professor and ARC Future Fellow, University of Western Australia and author of Geocultural Power: Chinaʼs Quest to Revive the Silk Roads for the Twenty First Century (University of Chicago Press, 2019). See: www.silkroadfutures.net