Hong Kong, Huawei, the persecution of Xinjiang’s Uyghurs – China has dominated much of 2019’s headlines in international affairs. And while the United States is increasingly embracing the return of great power competition as its foreign and security paradigm, Europe and Germany in particular continue to grapple with the question of how to square an indispensable economic partnership with increasing security concerns.

To be sure, the increasing uncertainty over transatlantic relations is complicating the picture, with many European capitals reluctant to take up an argument with an increasingly irritable China for fear of fending on their own should Washington and China agree on a deal. However, amid signs that policymakers in Berlin are beginning to contemplate the limits of engaging China, is the changing debate reflected in public opinion?

Based on a recent study conducted by Körber-Stiftung and the Pew Research Center for The Berlin Pulse, two trends emerge:

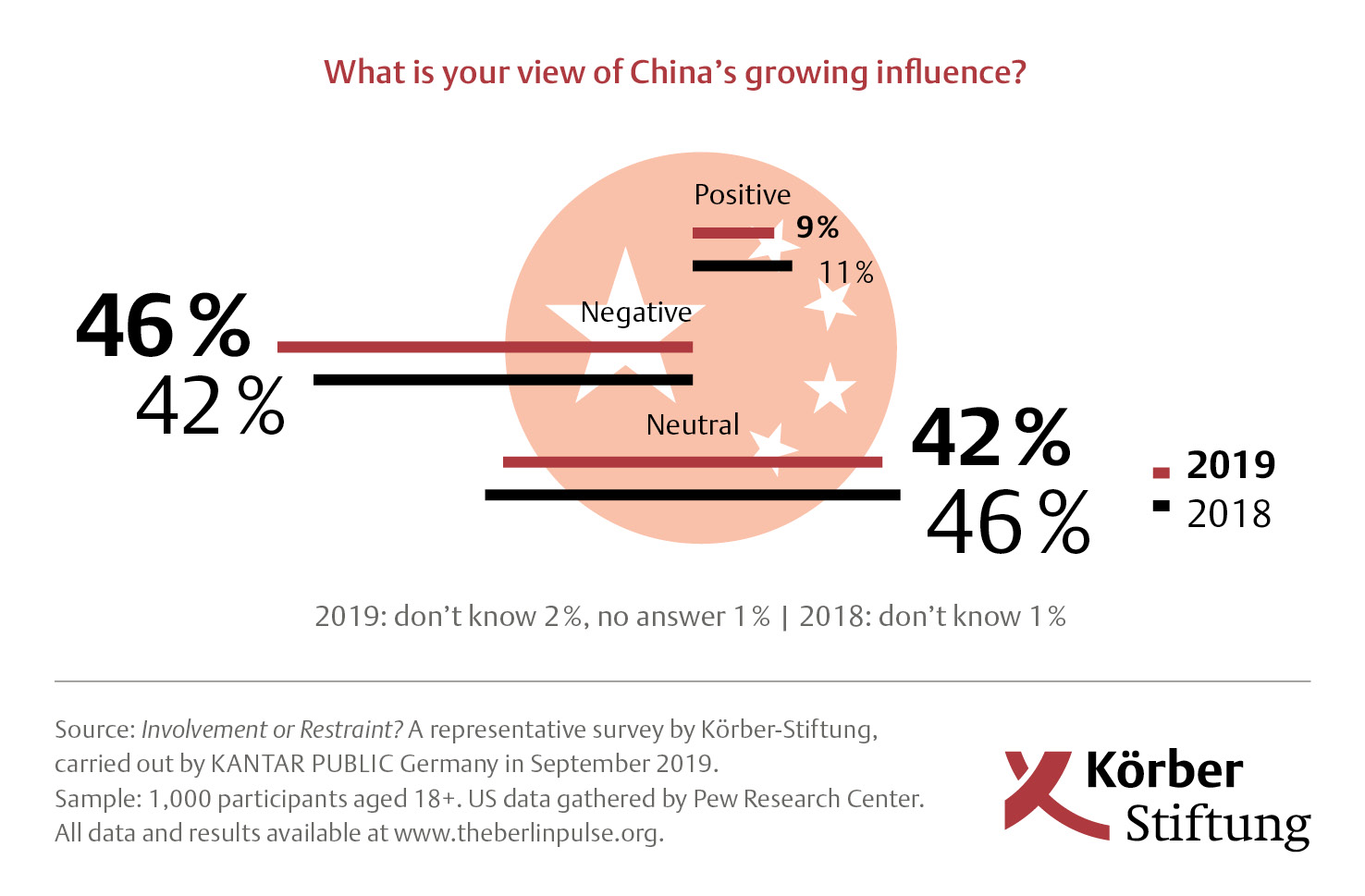

First, Germans are becoming increasingly skeptical of the Chinese party-state. Yes, 60 percent may favour more cooperation with China, but compared to 68 percent in 2018 the trend is negative. Moreover, only 9 percent perceive China’s growing influence in the world as positive, compared to 46 percent who regard it as negative. In a similar fashion, the vast majority (87 percent) reject the Chinese model of state capitalism, combining economic growth and authoritarian rule. Moreover, three quarters of the population (76 percent) feel that Germany ought to take a stronger stance in defending its political interests vis-à-vis Beijing, even in the face of adverse economic consequences.

Interestingly, it appears that German public opinion on the issue of China is much more closely aligned with Berlin’s expert community, the majority of which has warned of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s seeming openness to Huawei and encouraged policymakers to increase efforts to strengthen multilateralism and the international rules-based order, including in the South China Sea.

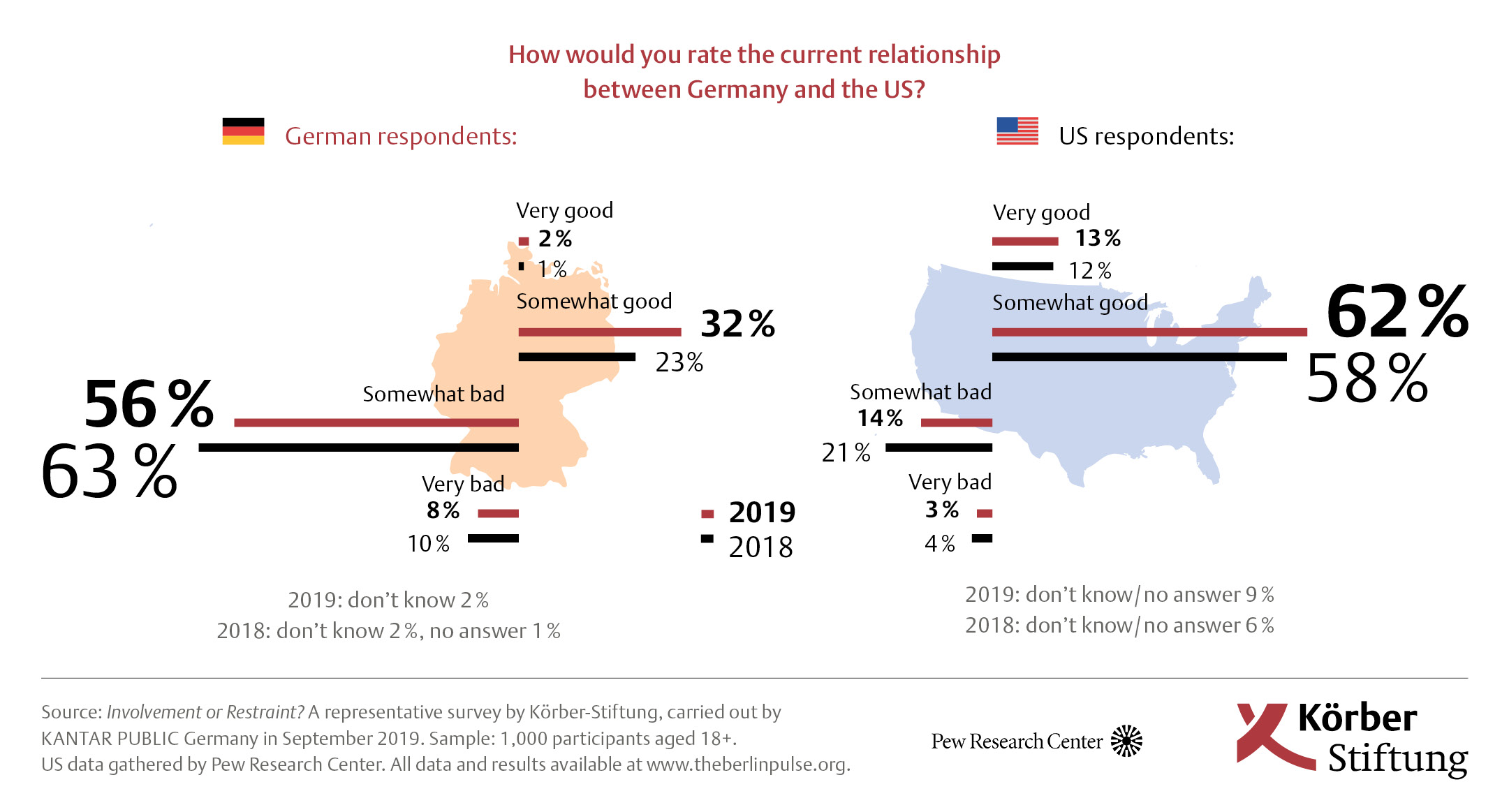

However, and second, the notion of a coordinated, transatlantic China strategy so far has gained little traction among the German public. While dynamics in China and the resulting debate on how Germany should position itself toward Beijing have clearly affected public opinion, the presidency of Donald Trump have has even more impact. Despite the role played by the United States from reconstruction after World War II to German reunification, 64 percent of Germans feel that relations with the United States are currently bad. Three years into the Trump administration, the results of transatlantic dissonance are becoming ever more obvious.

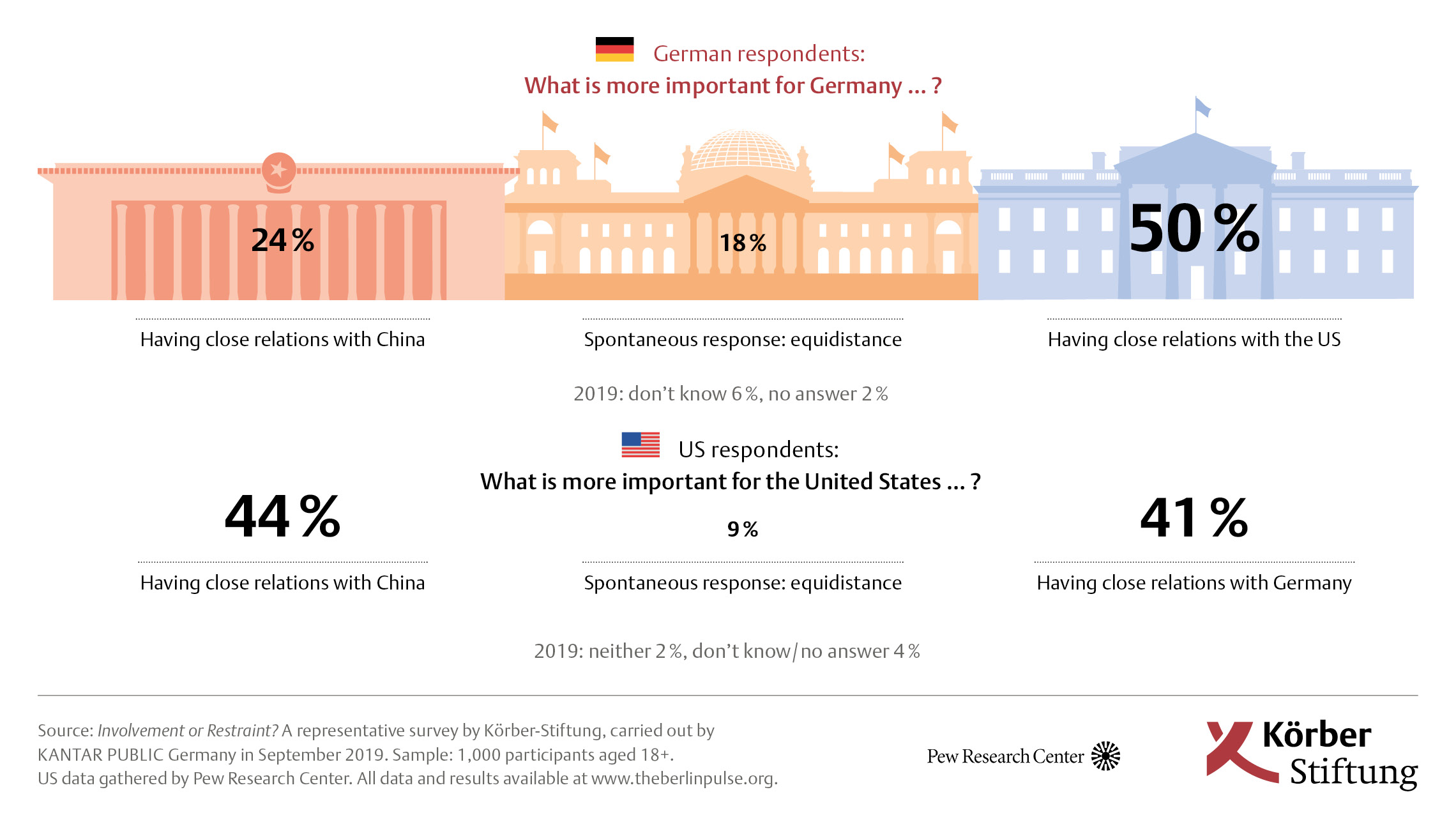

Peter Altmaier, Berlin’s Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy and a close confidant of Chancellor Merkel, recently cited the 2013 NSA affair to argue that the risk of Chinese espionage provided insufficient grounds to ban Huawei from Germany’s 5G networks. While Altmaier was roundly criticized for creating a false equivalence between China and the United States, the German public feels similarly ambivalent: Only 50 percent of Germans believe that close relations with Washington are more important than keeping close to Beijing, compared to 18 percent in favour of equidistance and 24 percent in favor of prioritizing relations with China.

What follows is that there is little support for a transatlantic China strategy. To the contrary, 52 percent of Germans would be willing to tolerate a doubling of defense expenditure for the sake of a foreign and security policy that was less dependent on the United States. Similarly, a majority of 54 percent is explicitly against Germany following the U.S. example of adopting a tougher trade policy toward China. Whereas the German Federation of Industries in January published a paper including policy recommendations for a more assertive trade and industrial policy, the German public does not seem overly concerned about the problems facing its companies in Beijing.

There are silver linings, too: 49 percent of Germans believe that Berlin should take part in naval missions to protect freedom of navigation and maritime trade routes. Examining the bigger picture though, while German interests are clearly at stake in East Asia, Germans appear decidedly less enthusiastic about a more active foreign policy. However, Europe is not an island, and much as Germans may wish, keeping aloof from the complex, challenging realities of foreign policy is not a sustainable option for Europe’s largest economy. As Germany’s partners both in Europe and across the Indo-Pacific region are calling on Berlin to increase its engagement across the region, policymakers in Berlin face the choice of explaining to an anxious electorate why and how Berlin ought to defend its interests, lest they look back in the not-too-distant future and realize they missed their chance.

Joshua Webb is editor of The Berlin Pulse for Körber-Stiftung.