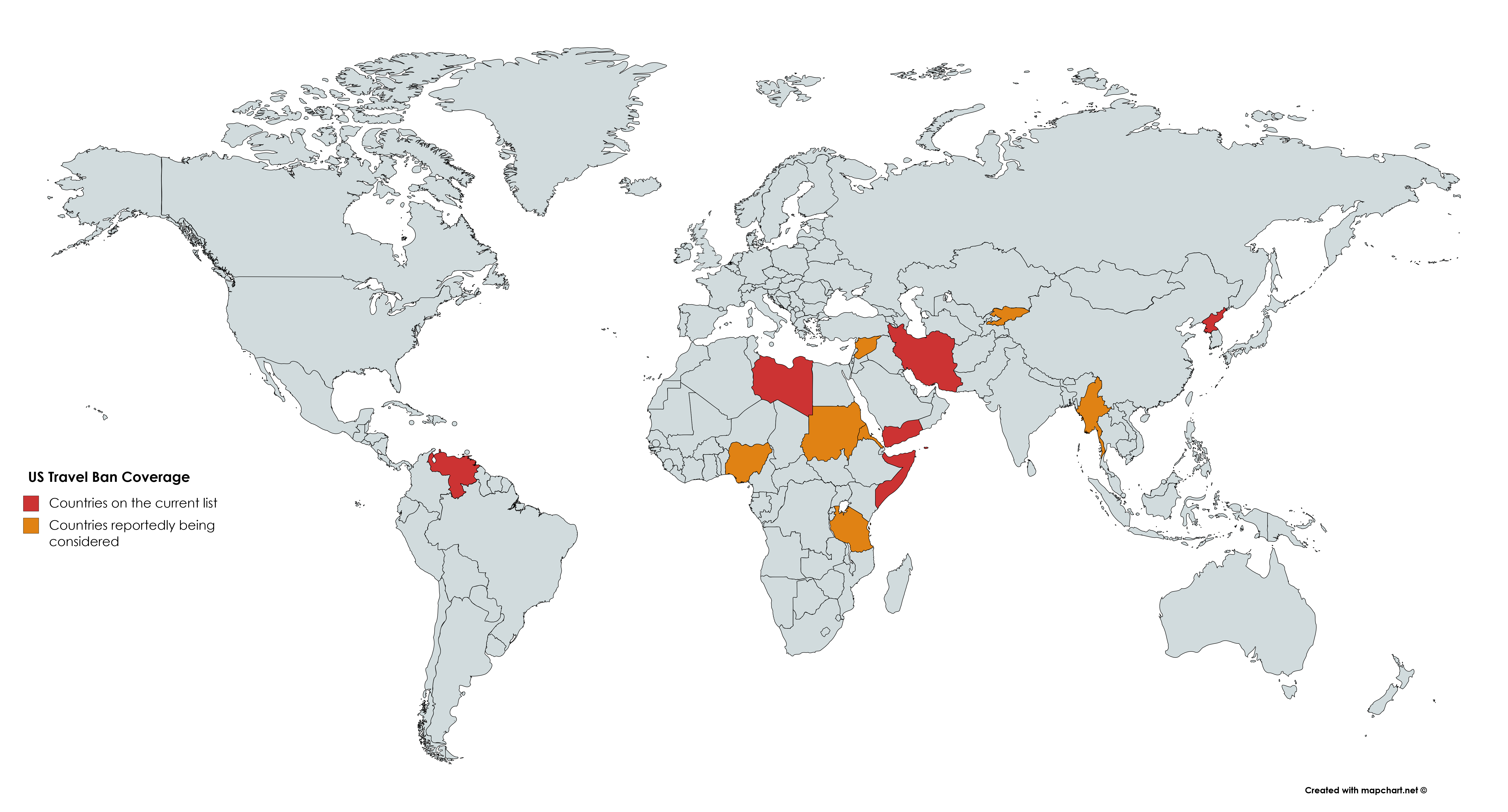

U.S. President Donald Trump is expected to announce the addition of new countries to the controversial U.S. travel ban in the coming week. Trump, whose original ban included countries such as Iran, Libya, and North Korea, is reportedly considering adding Myanmar (along with Kyrgyzstan, Belarus, Eritrea, Nigeria, Sudan, and Tanzania) to the list.

Exact details of the policy – including whether the ban will apply to all citizens from those countries or target particular visa classifications or personnel, and for how long — are still unknown.

The decision to include Myanmar in the expanded list may be in response to the Rohingya crisis on Myanmar’s western border, where the military government stands accused of carrying out a genocide against the minority-Muslim population. The violence and unrest have ignited a refugee crisis over the border in Bangladesh.

Although the Trump administration would be right to condemn the actions of the Myanmar government in Rakhine state, levying travel sanctions against the Southeast Asian country is a mistake. Such measures would only serve to deepen the isolation of a country well-versed in digging in its heels amidst international pressure and alienate the hard-working immigrants and students from Myanmar in the United States. Media reports on the potential travel ban have been unsettling to members of the diaspora in the United States, whose ability to visit family may be in question.

Continued engagement with the Myanmar government is critical for the United States to have an answer to China’s Belt and Road Initiative. By implementing this travel ban, the Trump administration would push Myanmar — a country looking to leverage its natural resources to drive exports – into a monopsony market, with China as the sole buyer.

The Chinese, wary of depending on the Strait of Malacca for its maritime trade, have long been eyeing an overland route through Myanmar to connect with a proposed deep-sea port in Kyaukphyu. Other Chinese infrastructure projects in Myanmar abound, including large scale construction, hydropower, and rail projects. The fate of nearby Cambodia, a nation dominated by Chinese industry, is a stark warning of what over-reliance on China could mean for Myanmar.

It is vital for U.S. and Western interests in the region to offer Myanmar an alternative to Chinese money. Isolating Myanmar by implementing additional sanctions works against this goal and weakens U.S. standing in the region.

Beyond international political considerations, there are U.S. domestic matters to consider. The constitutionality of the new ban will be promptly challenged. The travel ban as it exists today required three separate iterations before being accepted by the Supreme Court, drawing comparisons by dissenting Justice Sonia Sotomayor to Korematsu vs. United States, the 1942 decision permitting Japanese internment. Any update to the travel ban ought to attract a similar level of scrutiny in the public and in the courts.

It is not clear what the Trump administration hopes to achieve by adding Myanmar to the travel ban. America is not in a position where it needs to stem the flow of refugees affected by conflict from Myanmar – indeed, less than 600 Rohingya were resettled in the United States in 2019. If the target is the upper echelons of government and the perpetrators of violence, surely targeted financial sanctions would be more appropriate than a sweeping travel ban. As the ostensible purpose of the original ban was “to prevent terrorist or criminal infiltration by foreign nationals,” it’s an open question whether Myanmar’s consideration for inclusion means the Trump administration believes the Myanmar government’s assertions that its crackdown on the Rohingya is necessary to combat a terrorist threat.

We will have to wait for the official White House announcement before making too many assumptions about Trump’s intentions – but given that the U.S. president did not know where Myanmar was as recently as this summer, there’s good reason to be skeptical about this policy change.

Daniel O’Connor is a graduate of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, with a concentration in Asia-Pacific Affairs and International Law. Prior to that he lived for four years in Southeast Asia, much of that time in Myanmar.