Election security has emerged as a global challenge to democracies, which are now frequently subjected to foreign-based cyberattacks and disinformation campaigns seeking to influence the outcome of elections. With Taiwan’s national elections just days away, increased attention now falls on the role of China.

In November, Wang Liqiang, a Chinese national now seeking asylum in Australia, claimed that he had worked on behalf of China to influence the Taiwanese elections. Now days before the Taiwanese election, it is being reported that Wang stated he was offered financial incentives to retract his claim and accuse Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen of bribing him to make his revelations. According to Australian publication The Age, “The two men suspected of coordinating the directives [to Wang] are controversial Taiwanese political figure Alex Tsai and a China-based businessman called Mr. Sun. Mr. Tsai is a former legislator and a current deputy secretary of Taiwan’s main opposition party, the Kuomintang (KMT), which is opposing President Tsai in the election.”

The ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), spearheaded the adoption of an anti-infiltration law in late December, in large part due to concerns over Chinese disinformation efforts, while the opposition KMT condemned the effort as overly vague and an affront to freedom of speech without a government body in charge of implementing it. Furthermore, the KMT has blamed the DPP for the spread of disinformation, with one KMT spokesperson referring to President Tsai as “the commander of all the fake news.”

But what does the Taiwanese public think about Chinese influence in the election?

Chinese efforts to influence Taiwanese public opinion are nothing new, but the blatant propaganda of the 1950s has been replaced with sophisticated technological tools. Taiwan suffers approximately 10 million cyberattacks a month with most of the attacks coming from China. Chinese agents also commonly spread disinformation on social media and news outlets to alter Taiwanese people’s opinions of candidates. When logging on to social media or reading digital news websites, Taiwanese voters come across debunked stories with headlines such as “Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s PhD is fake” or “The CIA pays Hong Kong protestors $385 a day to go on the streets.” The Varieties of Democracy Institute in Sweden categorized Taiwan as one of the three places where foreign governments are most likely to spread disinformation.

China’s efforts to influence Taiwanese elections predate the 2020 elections. In 2018, China was believed to have spread “fake news” on Taiwanese- and Chinese-owned media to aid China’s preferred candidates in local elections. In 2019, it was discovered that Chinese cyberattackers had also been using computers to spy on Taiwanese, possibly since 2013. Foreign Policy found that the Strategic Support Force of China’s army could have flooded Facebook and other social media sites with disinformation to help current KMT presidential candidate Han Kuo-yu win a shocking upset in the Kaohsiung mayoral race. China now appears to being using improved cyber techniques, including artificial intelligence, to imitate the diction of Taiwanese voters.

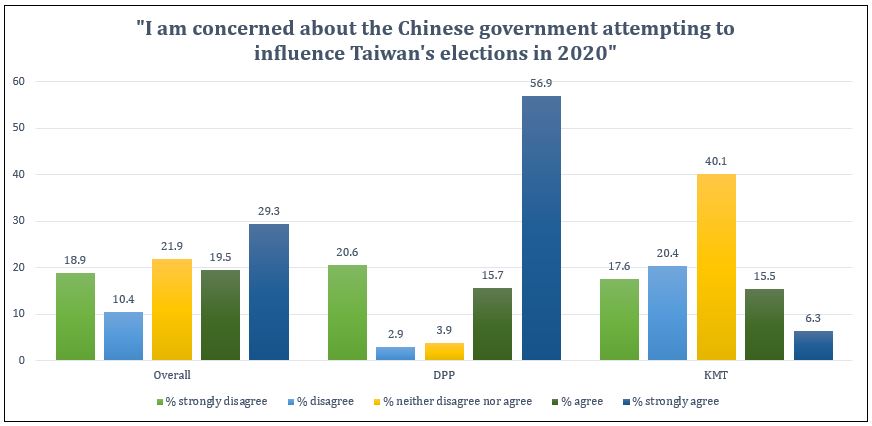

We wanted to identify whether Taiwanese were concerned about Chinese influence in the election. We conducted a web survey through PollcracyLab at National Chengchi University’s (NCCU) Election Study Center December 9-11 of 2019. This predates the passage of the anti-infiltration law but not the initial claims made by Wang or concerns about Chinese influence. In the survey, 502 respondents were first asked to evaluate the following statement on a five-point scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree:

I am concerned about the Chinese government attempting to influence Taiwan’s elections in 2020.

Next, respondents were randomly assigned to receive one of two prompts and asked to again evaluate it on a five-point scale. The versions were:

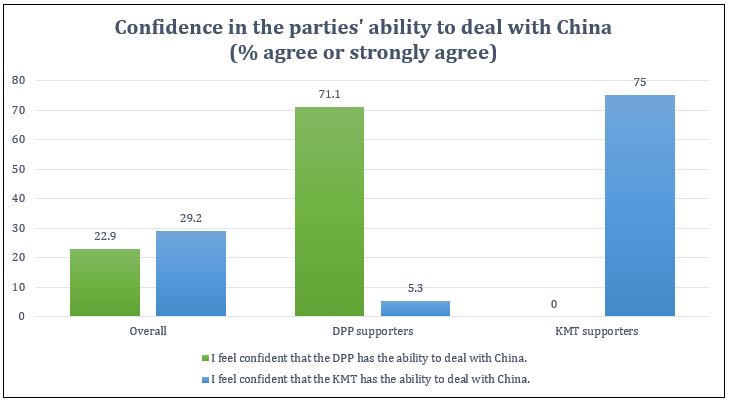

Version 1: I feel confident that the DPP has the ability to deal with China.

Version 2: I feel confident that the KMT has the ability to deal with China.

Overall, evaluations of both parties are rather poor, both under 30 percent, with views of the KMT slightly higher. Removing the respondents that support one of the two largest parties drops these evaluations further, to 18.4 percent for the DPP’s ability compared to 11.7 percent for the KMT. Once the focus shifts to the supporters of the two largest parties, we see that respondents not only exhibit high confidence in their preferred party, as expected, but remarkably low rates of confidence in the opposition’s ability to deal with China.

Admittedly, using the term “deal” is vague and a partisan could read this not as an inability to interact with China, but as promoting policies counter to their own preferences (e.g. a DPP person concerned that KMT “dealing with China” means returning to the “1992 Consensus”). Likewise, that the question followed the interference question may prime respondents to think solely in terms of responding to election interference. Even if that were the case, the results suggest the strong power of partisan attachments.

We cannot directly measure how breaking allegations of Chinese interference in the election will influence public opinion this close to the polls. However, we expect that Taiwanese will view these claims through their existing partisan lenses. The hyper-polarization in views between DPP and KMT supporters highlights the difficulty in addressing cybersecurity and China more broadly. To reach a consensus requires first acknowledging and disrupting the echo chambers in which disinformation campaigns thrive, then the government must implement election transparency policies to more easily expose disinformation efforts. However, with increasing animosity between parties, this consensus may be hard to reach. Citizens may also be concerned that any steps the government takes are limiting their freedom of speech or other rights.

Taiwan needs to revamp its cyber policy to adequately respond to threats. Fortunately, Taiwan is taking steps in the right direction with the anti-infiltration law and joint cyberwar exercises with the United States. While such efforts help protect official government websites from attacks, they do little to stop the spread of disinformation on social media or make Taiwanese citizens more cognizant of the challenge of disinformation campaigns on democratic elections.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University. His main area of research focuses on the electoral politics in East Asian democracies.

Madelynn Einhorn is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Political Science and Economics.

Isabel Eliassen is an Honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University majoring in International Affairs, Chinese, and Linguistics.

Carolyn Brueggemann is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in International Affairs, Spanish, and Chinese.

Alexandrea Pike-Goff is an undergraduate researcher at New York University majoring in Politics and Human Rights, with a focus on East Asia.